From Eco-religion to Political Ecology in India: Feminist Interventions in Development

The UN Millennium Declaration in September 2000 committed world leaders to greater global efforts to reduce poverty, improve health and promote peace, human rights and environmental sustainability. This declaration sought to achieve by 2015 the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which include reducing hunger; achieving universal primary education; promoting gender equality (especially in education) and empowering women; reducing child mortality; improving maternal health; combating major diseases; ensuring environmental sustainability; and strengthening partnerships between the rich and poor countries. The MDGs regard empowering women and environmental sustainability as the key factors for development, and demand a renewed look at indigenous models of living in which women play an important role in environmental conservation.

The existence ofpeople of India eco-religious practices among the points to the long standing traditions of ecological conservation and a culture of nurturing nature (Prasad, 2001). These traditions are undergoing a transformation to emerge as a political ecology that is gaining currency in the development discourse. Women have played a significant role in effecting the transformation of eco-religion to a political ecology in which sustainable environment will be the touchstone of development. This paper will focus on women’s interventions and activism to mainstream sustainable environment in the context of the emerging political ecolog y in India. This paper also highlights the case of the Narmada Bachao Andolan against big dams spearheaded by the veteran environmentalist, Medha Patkar.

transformation to emerge as a political ecology that is gaining currency in the development discourse. Women have played a significant role in effecting the transformation of eco-religion to a political ecology in which sustainable environment will be the touchstone of development. This paper will focus on women’s interventions and activism to mainstream sustainable environment in the context of the emerging political ecolog y in India. This paper also highlights the case of the Narmada Bachao Andolan against big dams spearheaded by the veteran environmentalist, Medha Patkar.

Lakh

One hundred thousand.

Source: www.dictionary.com Eco-Religion in India

Ancient Indians developed many ideas, attitudes and practices which favoured the maintenance of ecological balance for the welfare of all. These views are reflected in several philosophical and religious texts of the Vedas and Puranas which form the basis for an environmental ethics. In Advaita philosophy, the universe acquires a cosmic character as it considers all living beings to be God’s creation. This doctrine provides the philosophical basis for the Indian veneration of the natural world, which leads us to think that Indian tradition has an ecological conscience (Crawford, 1982: 149-150).

Ancient Indians advocated an integrated approach to progress without undue exploitation of natural resources. They laid down traditions, customs and rituals, to ensure that the complex, abstract principles they had developed could be put into practice. Over time, these practices developed agricultural technology, methods of environmental protection, and knowledge of medicinal properties of trees (Banwari, 1992). About ten percent of the indigenous tribal population (adivasis) in India continues to practice shifting cultivation. A total area of about 50 lakh hectares over 15 states, are covered by this shifting cultivation in India. The land is not ploughed in this type of farming and neither is there any need for domesticating animals. The cultivators have total confidence in the generative power of the earth and see no need to resort to eco-destructive methods. At the end of summer, the hillsides are prepared for cultivation by trimming the undergrowth of bushes and shrubs. These are then burnt and the ashes provide the manure. Before the monsoon sets in, the shrubs and bushes are set on fire again. As soon as the rains come, the seeds are cast and the earth is activated to produce a rich harvest. This method of farming is known as Koman in Orissa, Podu in Andhra Pradesh, Bewar in Madhya Pradesh, Kureo in Bihar, Jhum in Assam, Tekonglu in Nag aland, Adiabik in Arunachal Pradesh and Hooknismany in Tripura (Vadakumchery, 1993).

Source: www.goodnewsindia.com

Cultivation is carried on for three years at a stretch, and usually, the harvest is enough to meet the needs of the community. Shifting cultivation is based on the eco-religious faith in Mother Earth’s power creation without artificial inputs. After cultivating the same area for three years, when the fertility of the land declines, it is left fallow to regain its vitality. Cultivation during this period is then shifted to another area. The religious belief that ploughing is painful to Mother Earth and, therefore, an inferior form of cultivation, has led the indigenous and tribal communities to practice shifting cultivation which, for, them, has divine sanction.

For the Bishnois, Biodiversity is a Way of Life The importance of eco-religion in environmental conservation is shown in the outstanding case of the Bishnois of Rajasthan, a north-western state which has vast tracts of deserts. The protection of trees and animals is a religious obligation (Shar ma, 1999) for the Bishnois. They follow a set of 29 rules, which talk of how they should live and what should be done after their death. The faith that God adequately compensates the cultivators for all the losses caused by animals, underlines the basic philosophy of the Bishnoi religion that all living things (including animals) have a right to survive and share all resources.

Guru Jambeshwarji, or Jamboji as he is affectionately referred to by his followers, founded the Bishnoi religion in 1542 AD. He was a great saint and a philosopher of medieval India. Those who follow his 29 tenets are called Bishnois (literally meaning twenty-nines’ in Hindi). The tenets were designed to conser ve the biodiversity of the region and ensure a healthy eco-friendly social life.

The religious belief that ploughing is painful to Mother Earth and, therefore, an inferior form of cultivation, has led the indigenous and tribal communities to practice shifting cultivation which, for, them, has divine sanction.

Of the 29 tenets, ten are concerned with personal hygiene and the maintenance of good health, seven are about healthy social behaviour and five are concerned with worship. Eight tenets aim to preserve biodiversity and encourage good animal husbandry. These include a ban on killing of all animals and felling of green trees. Urged to protect all life forms, the community has even been directed to make sure that firewood is free of small insects before it is used as fuel. Wearing blue cloth is also prohibited because the blue dye is obtained from particular shrubs which have to be cut for extracting the colour. The Bishnois are currently spread over the western region of Rajasthan and parts of Haryana and Punjab. They are more prosperous than other communities living in the Thar deserts, probably because of their eco-friendly life. Their villages are easily distinguishable because of numerous trees and vegetation near their homes, and herds of antelopes roaming freely. Fields are ploughed with simple tools using bullocks or camels, which causes minimal damage to the fragile desert ecosystem. Only one crop of bajra is grown during the monsoon season. The bushes which grow in the fields protect the loose sand from wind- erosion and provide the much needed fodder for animals during famine. The Bishnois keep only cows and buffaloes, as rearing of sheep and goats which devour desert vegetation, is taboo. Though they are Hindus, they do not burn their dead but bury them to save precious wood and trees. They store water year round in underground tanks by collecting precious rain water.

It is this environmental awareness and commitment to conservation and protection that make Bishnois stand out from other communities in India

The Bishnois follow an old tradition of protecting trees and animals. In 1737, when officials of the Maharaja of Jodhpur started felling a few khejri trees in Khejerli village, all the inhabitants including women and children, galvanised into action by a woman called Amritadevi, hugged the trees that were being axed. In all, 363 Bishnois from Khejerli and adjoining villages sacrificed their lives. Later, when he came to know of it, the Maharaja apologised for his action and issued a royal decree engraved on a copper plate, prohibiting the cutting of trees and hunting of animals in all Bishnoi villages. Violence of this order by anyone, including members of the ruling family, was to entail prosecution and a severe penalty. A temple and a monument stand as a remembrance of the 363 martyrs. Every year, the Bishnois assemble here to recall the people’s extreme sacrifice to preserve their faith and religion.

Up till now, the Bishnois aggressively protect the khejri trees and the antelopes, particularly the blackbuck and chinkara. They consider protecting a tree, even if it be at the cost of one’s head, a good deed. They not only protect antelopes but also share their food and water with them. In a number of villages, the Bishnois feed animals with their own hands (Sharma, 1999). They keep strict vigil against poachers. Interestingly, a popular actor who was recently accused of hunting a deer in a Bishnoi village had to face the ire of the local population and prosecuted according to state law.

If poachers leave behind a dead antelope when escaping, the owner of the field on which it is found, mourns its death like that of a beloved, and does not eat or even drink water until the last rites are performed. On many occasions, poachers have wounded or killed Bishnois but villagers fearlessly keep vigil to protect the blackbuck and chinkara, which roam freely. It is this environmental awareness and commitment to conser vation and protection that make Bishnois stand out from other communities in India (Sharma, 1999). The Bishnois’ eco- religion has inspired many women’s groups and local communities to take on powerful lobbies that support development based on unbridled exploitation of natural resources and environmental neglect.

Women Spearhead Movements in Political Ecology

The fast expansion of cities in India has led to deforestation and conversion of highly productive lands to meet the demands of industrialisation and urbanisation. Deforestation has a direct bearing on women’s daily lives: women find it harder to secure domestic fuel and fodder in rural areas as well as other products used within the household. A study conducted in a Himalayan village in Chamoli district of Uttar Pradesh revealed that each household spends between six to ten hours every day on collecting fuel and fodder. This involves an uphill climb of five kilometres with constant danger from wild animals (CSE, 1985).

Women in the rural areas depend on forests not only for meeting their subsistence needs, but also for income and employment. This includes activities such as making rope from different types of grasses, weaving baskets, rearing tassar silk cocoons, lac cultivation, making products from bamboo and oil extraction, selling sal seeds and tendu leaves (Venkateswaran, 1995: 58). Thus, deforestation also results in job losses for the poor women, especially when they are self-employed.

Rural women have realised that the key to economic progress should be ecologically sustainable and satisfy the basic needs of the community. Women’s activism to address this development gap has historical roots in the struggles for nationalism, worker’s rights and peasant struggles. These struggles have given rise to several grassroots people’s movements, in which women are actively involved, to protect the environment in a bid to conserve local resources. In the Himalayan hills of Uttar Pradesh, people collectively rose to defend local interests against timber logging by contractors and private agencies that has jeopardised ecological stability and reduced local people’s opportunity to benefit from sound forest exploitation. The Chipko movement, which originated in the hills of Uttar Pradesh, was spearheaded by women who protected the trees from felling by hugging them.

The Appiko movement similarly originated as a forest protection movement in Karnataka. Both movements led by women draw inspiration from the Bishnoi eco-religious philosophy of harmonious living blended with environment conservation. Women are beginning to transform this environmental philosophy into a political ecology where policymakers have often heeded women’s intervention in forest protection and ordered a stop to the large-scale felling of trees. Against this backdrop, it is interesting to examine the case of the Nar mada anti-dam movement spearheaded by Medha Patkar, an extraordinary woman, over a period of two decades and its entry into the realm of political ecology.

The Narmada Bachao Andolan movement

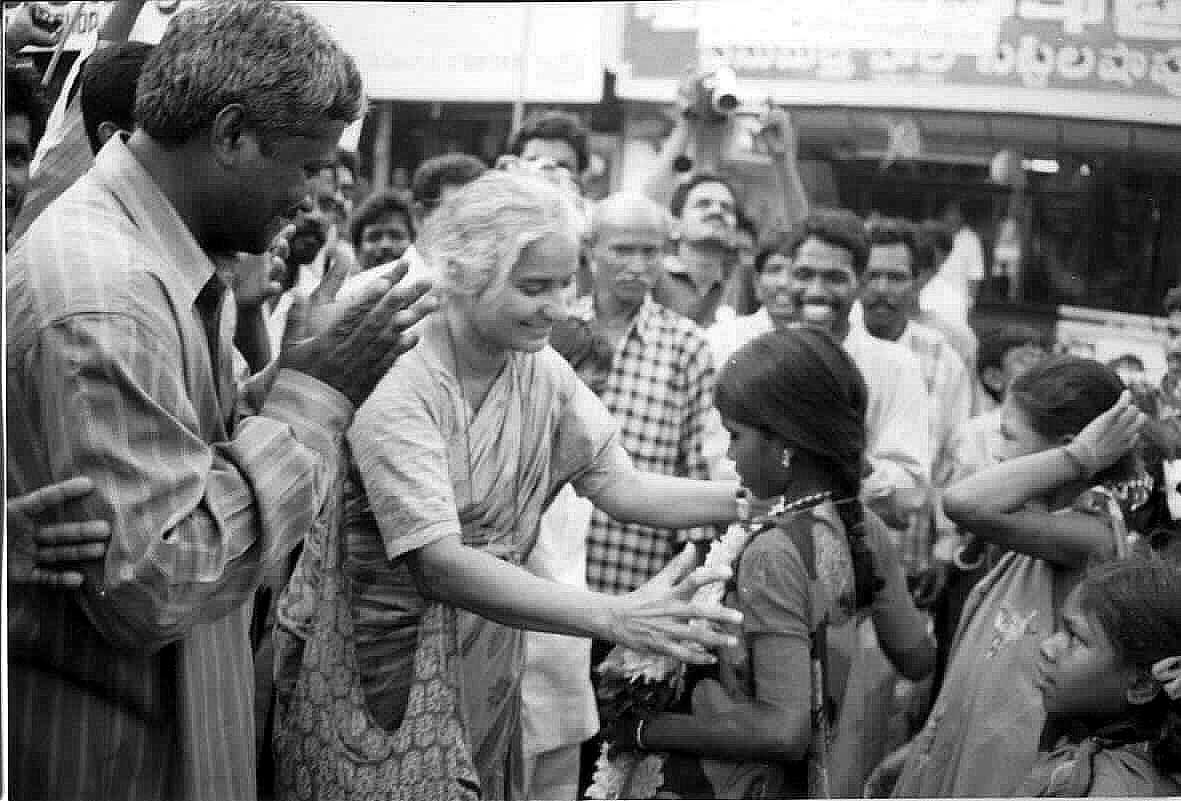

Medha Patkar is well-known the world over as a powerful voice of millions of the voiceless poor and oppressed people. Medha Patkar, founder of the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA) and the National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM), is immersed in the tribal and peasant communities in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, which she eventually organised as the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Struggle to Save Narmada River). Facing police beatings and many jail terms, a veteran of several fasts, and monsoon satyagrahas (marches) on the banks of the rising Narmada, her uncompromising insistence on the right to life and livelihood has compelled the post-Independence generation in India as well as around the world to revisit the basic questions of natural resources, human rights, environment, and development.

Medha Patkar has received numerous awards, including the Deena Nath Mangeshkar Award, Mahatma Phule Award, Goldman Environment Prize, Green Ribbon Award for Best International Political Campaigner by BBC, and the Human Rights Defender’s Award from Amnesty International. She is also one of the recipients of the Right Livelihood Award (the alternative Nobel Peace prize) for the year 1991. She has served as a Commissioner to the World Commission on Dams, the first independent global commission constituted to enquire on the water, power and alternative issues, related to dams, across the world.

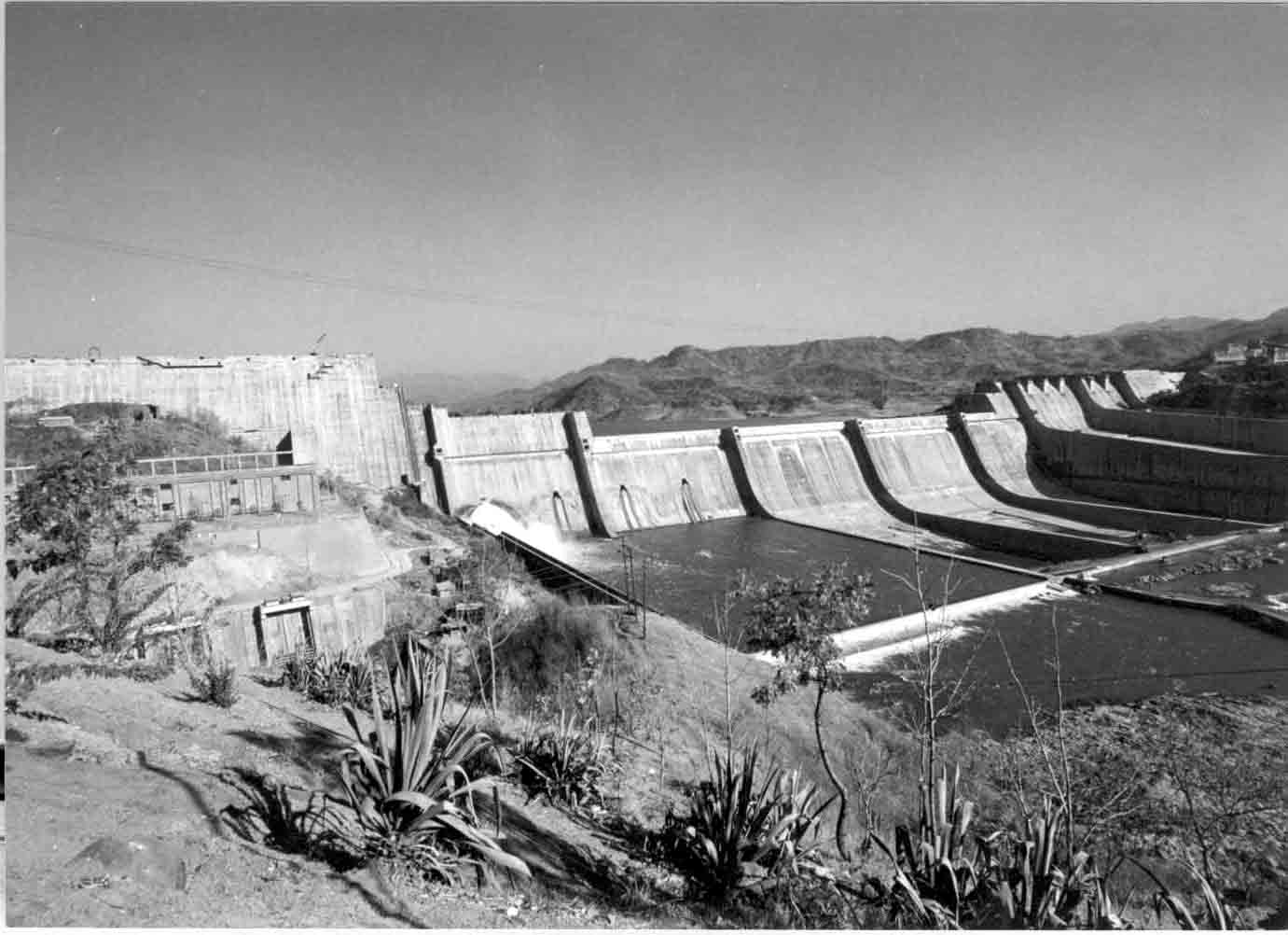

The Narmada Bachao Andolan began as a fight for information about the Narmada Valley Development Projects and continued as a fight from 1990-91 for the just rehabilitation of lakhs of people ousted by the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the world’s largest river projects, and other large dams along the Narmada River. The Sardar Sarovar Dam was a project that would displace upon completion 320,000 tribals and submerge over 37,000 hectares of land. When it became clear that the magnitude of the project precluded accurate assessment of damages and losses, and that rehabilitation was impossible, the movement challenged the very basis of the project and questioned its claim to“development.”

The Narmada Bachao Andolan began as a fight for information about the Narmada Valley Development Projects and continued as a fight from 1990-91 for the just rehabilitation of lakhs of people ousted by the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the world’s largest river projects, and other large dams along the Narmada River. The Sardar Sarovar Dam was a project that would displace upon completion 320,000 tribals and submerge over 37,000 hectares of land. When it became clear that the magnitude of the project precluded accurate assessment of damages and losses, and that rehabilitation was impossible, the movement challenged the very basis of the project and questioned its claim to“development.”

Medha Patkar has been a central organiser and strategist of NBA, a people’s movement organised to stop the construction of a series of dams planned for India’s largest westward flowing river, the Narmada. The World Bank-financed Sardar Sarovar Dam is the keystone of the Narmada Valley Development Project, one of the world’s largest river development projects. Upon completion, Sardar Sarovar Dam would submerge more than 37,000 hectares of forest and agricultural land. The dam and its associated canal system would also displace some 320,000 villagers, mostly from tribal communities, whose livelihoods depend on these natural resources. Among India’s most dynamic activists, Medha knows the Narmada Valley hamlet by hamlet. Equally fleet-footed on the narrow mountain paths with only a torch and the light of the moon and stars, or on the Indian Railways, all the ticket collectors are familiar with her traveling office—documents, banners, pamphlets.

In 1985, Patkar began mobilising massive marches and rallies against the project, and, although the protests were peaceful, she was repeatedly beaten and arrested by the police. She almost died during a 22-day hunger strike in 1991. Undaunted, she undertook two more long protest fasts in 1993 and 1994. With each subsequent summer monsoon season, when flooding threatens the villages near the dam site, Patkar has joined the tribals in resisting evacuation and resigning themselves to drown in the rising waters. In 1994, the NBA office was ransacked, and later Patkar was arrested for refusing to leave the village of Manibeli which was to be flooded. To date, as many as 35,000 people have been relocated by the project; however, they have not been adequately resettled and hundreds of families have returned to their home villages despite the constant threat of submergence.

These actions led to an unprecedented independent review of the dam by the World Bank, which concluded in 1991 that the project was ill-conceived. Unable to meet the Bank’s environmental and resettlement guidelines, the Indian government canceled the final installment of the World Bank’s $450 million loan. In 1993, Medha Patkar and her co-activists forced the central government to conduct a review of all aspects of the project. Meanwhile, the sluice gates to the dam were closed in 1993, in defiance of court orders, and water was impounded behind the dam.

In May 1994, NBA took the case to stop the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam to India’s Supreme Court. In January 1995, the Supreme Court put a stay on further construction of the half-built dam and has tried to forge consensus between the central and state governments. While state governments continue to push for an increase in the height of the dam, displaced tribals carry on with mass protests. Patkar continued to defy the project and in 1996, she was again arrested.

The NBA has also been working to obtain just compensation for people affected by dams which have already been built on the Narmada as well as opposing other dams in the Narmada Valley. In 1997, the NBA helped tribal communities stop construction of the Upper Veda and Lower Goin dams. Another focus of the NBA’s work has been the Maheshwar Dam.

A number of huge rallies and dam site occupations forced a halt to major work on this project and led the state government to establish an independent task force to review the dam. On October 18, 2000, the Supreme Court of India allowed construction on the dam up to a height of 90 metres. The judgment also authorised construction up to the originally planned height of 138 metres in five-metre increments subject to the Relief and Rehabilitation Subgroup of the Narmada Control Authority’s approval. Booker Prize winning author-turned activist Arundhati Roy courted arrest for contempt of court for her outspoken criticism of the 2-1 majority judgment.

As an outgrowth of her work to stop dam construction, Patkar has helped establish a network of activists across the country—the National Alliance of People’s Movements. Linking the Nar mada Bachao Andolan with hundreds of peasant, tribal, dalit, women and labour movements throughout India, Medha Patkar is Convener of the National Alliance of People’s Movements—a non-electoral, secular political alliance opposed to globalisation—liberalisation-based economic policy and for alternative development paradigm and plans. The construction of large dams on the River Narmada in central India, and its impact on millions of people living in the river valley has become one of the most important social issues in contemporary India.

Medha Patkar says...“There is no other way but to redefine ‘modernity’ and the goals of development, to widen it to a sustainable, just society based on harmonious, non-exploitative relationships between human beings, and between people and nature.”

Medha Patkar says: “If the vast majority of our population is to be fed and clothed, then a balanced vision with our own priorities in place of the Western models is a must. There is no other way but to redefine ‘modernity’ and the goals of development, to widen it to a sustainable, just society based on harmonious, non-exploitative relationships between human beings, and between people and nature.”

She is a torch-bearer in promoting the Gandhian model of development that has human uplift and welfare as its core philosophy. Her two-pronged approach of struggle (sangharsh) and constructive work (nirman) has resulted in community participation to develop alternatives in energy, water harvesting, and education for tribal children. Among the notable local initiatives is the Reva Jeevanshala, using both state and local syllabus taught by local teachers in the local language. It is a system of nine residential schools and four day-schools in the tribal villages of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat. She has effectively demonstrated that the participatory approach to development is an alternative way forward that will ensure a satisfactory quality of life to millions struggling for basic needs.

The Narmada Control Authority gave a green signal on March 8, 2006 to raise the height of the Sardar Sarovar Dam from 110.64 metres to121.92 metres. On March 29, 2006, Medha Patkar and two activists began a fast unto death against this decision. She was forcefully taken to New Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences when her health became critical after eight days of fasting.

Patkar and her Narmada Bachao Andolan colleagues protested in New Delhi against the government’s decision saying the raising of the height of the dam is illegal, as the Supreme Court had ruled that the height cannot be increased without rehabilitating every affected family. She ended her 20-day fast in New Delhi on April 17, 2006, satisfied with the order of an Apex Court order on April 17, 2006 that said work would continue but the court would review the rehabilitation process.

How could the government make plans to bulldose a culture, a way of life steeped in history without consulting or rehabilitating the people who would be affected was her question. The question became the movement.

According to Medha, the issue is not just about one dam, though the trigger is. The Government of India plans to build 30 large, 135 medium and 3,000 small dams on the Narmada River and its tributaries. The government says the dams will provide much-needed water and electricity to drought-prone areas in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh. The agitators agree that water and electricity shortage in parts of Gujarat, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh are real. But they say there are alternate ways to address those problems. They argue that the millions of poor and underprivileged people will lose their livelihood, their land, their identity—thanks to the dams. The NBA also says that the concept of big-dam mode of development is fundamentally flawed. Her strug gle against the oppression of the poor tribals began with the demand of information about the development plans of the Narmada Valley. How could the government make plans to bulldose a culture, a way of life steeped in history without consulting or rehabilitating the people who would be affected was her question. The question became the movement.

On development and technology, Medha Patkar says: “I am not anti- technology, I am all for it: beautiful, harmonious, equitable, sustainable, egalitarian, non-destructive technology. Not this gigantic technology which is apocalyptic, destroying thousands of homes, hearts, habitats, ecolog y, geography, history, and finally, benefiting so few, and at such great cost. This is mindless and this is violence.”

Hers is a philosophy focused on seeing marginalised people achieve their rights. She has repeatedly raised the issues of mega projects, development planning, democratic and human rights, economics and corruption of monitory and natural resources by such projects and suggested that just and sustainable environmental alternatives in water, energy and other sectors are possible.

For 19 years, Medha Patkar has led the struggle for the people affected by the controversial Sardar Sarovar Project on the Narmada River in four States. A few years ago, she formed the National Alliance of People’s Movements with other activists against globalisation without a human face. From the NAPM has emerged the People’s Political Front (PPF) in 2006. In an interview, Medha Patkar threw light on the larger issues involved in the formation of the PPF and electoral politics. She believes that people’s movements are inevitable in any democracy to keep the democratic process alive and in raising and settling the conflicts between the state and the people on people’s issues. The PPF sees electoral and non-electoral politics as complementary to each other.

According to her: “It is necessary to challenge the changed culture of politics, which is criminal and communal to a large extent...Not only is it corporatised and corrupt, but crudely and confidently uses and misuses the resources of the country, with big industrial houses financing and controlling the parties… We have been raising these issues through our movements but somewhere we are peripheralised. We are not allowed the necessary space for questioning…We see this also as a satyagraha with certain goals of transformation. So we will not start calculating our probable successes and failures only with numbers, but would rather exhibit alternative ways of not only contesting elections, but also of politics” (The Hindu, March 28, 2004).

The PPF will question the present development paradigm which is not just consumerist but also exploitative and will also come up with alternatives. Medha says that the right to work as a fundamental right, which means that all economic politics and the choice of technology in management of resources, will necessarily have to aim at employment generation and livelihood protection. She believes that for this, it is necessary that the global capitalist forces are not allowed to influence policymaking. It will also follow on the other hand, the strengthening of the localisation of resource management and planning processes (The Hindu, March 28, 2004).

She considers politics also as a kind of movement. She says: “Just as we address the issues of livelihood and economic policies in our struggle, here we have to address the issues of political degradation and criminalisation and corporatisation.” Regarding the PPF’s agenda, she says: “We are for [a] secular agenda. We are not for allying with any party, but if any party supports the candidates emerging from [the] PPF, [there’s] nothing wrong with it. We know everything cannot be achieved in one election and it is not limited to only [one] election. The process between two elections is also going to be important” (The Hindu, March 28, 2004). She has now launched a yatra, named as Pole Khol Yatra to expose the fallacious claims made by various governments on rehabilitation of tribals displaced by the Sardar Sarovar Dam in the Narmada Valley. This is indeed going to be a long struggle of millions of poor and disadvantaged Indians against elite development models.

The Silver Lining

Women who were long neglected and silenced in the development processes have been awakened by national environmental movements like the NBA. Owing to the networking with the NBA, women in the local collectives/ federations have increased contact with the bureaucracy in the government offices. Prior to the networking with the National Alliance for People’s Movements, many women were unaware of where the government offices were located and played a minimal role in the political life of the country. Now, women representatives elected to the local government bodies visit the state offices and interact with officials and are also informed by them about various development programmes. In addition to greater interaction with government officials, networking with national organisations like the NAPM helps women to take up leadership roles in their own neighbourhoods, communities, and villages.

Nevertheless, the degree of power that autonomous women’s organisations can exert within the political process often determines the outcome in the form of appropriate policy changes for development. However, women’s empowerment is generally perceived as a matter of “low politics” and policy reforms and strategies are therefore influenced primarily by the extent to which different policies are likely to influence political stability (Heise, 1994). Now, there is a growing acceptance within the women’s movement that any strategy to achieve significant policy reforms at the state, regional or local level must engage the state and demand reform.

Nevertheless, the degree of power that autonomous women’s organisations can exert within the political process often determines the outcome in the form of appropriate policy changes for development. However, women’s empowerment is generally perceived as a matter of “low politics” and policy reforms and strategies are therefore influenced primarily by the extent to which different policies are likely to influence political stability (Heise, 1994). Now, there is a growing acceptance within the women’s movement that any strategy to achieve significant policy reforms at the state, regional or local level must engage the state and demand reform.

Women who attempt to reform the process of development by resistance against bureaucratic structures often find that an alliance of politicians and vested interests have an almost impregnable hold on the central institutions of society. The increasing poverty of these women often do not allow them to think leisurely and realise that the rise of popular protest which intends to bring in change must build up from the fringes of society to the centre until this becomes the dominant socio-political organisation in the country (Chakravarty, 2003:638).

Further, women’s extreme poverty and their pseudo enfranchisement in the developing countries sometimes make them realise that their powerlessness will not easily change their circumstances. This situation is complicated by policymakers who often ignore a world in which women are seldom leaders, doers and supporters of families, and where women’s concerns like poverty and lack of health care are absent or trivialised. But the struggle of women as narrated during the course of this paper is strongly founded on the hope that status and legitimacy will be bestowed on women’s issues. It does give an indication of women’s realisation of the changes in themselves as they prepare to raise difficult questions on the environmental sustainability of development projects. Women still have a long way to go. But when satisfactory answers are not forthcoming, women are gradually moving towards a position of seeking alternative models that put people’s welfare on the top of the agenda.

References

Banwari. (1992). Pancavati: Indian Approach to Environment (Tr. Asha Vohra), New Delhi: Sri Vinayaka Publications.

Chakravarty, M. (2003). “Communication for Women’s Empowerment: New dynamics and priorities.” In K. Prasad (Ed.), Communication and Empowerment of Women: Strategies and Policy Insights from India (Vol.2, pp. 627-641). New Delhi: The Women Press.

CSE. (1985). The State of India’s Environment, 1984-85: The second citizens report. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment.

Crawford, C.S. (1982). The Evolution of Hindu Ethical Ideals. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii.

Heise, et. al. (1994). “Violence Against Women: A neglected public health issue in less developed countries.” Social Science and Medicine (Vol.39, No.9, pp.1165-1179).

Jha, S. and Oza, N. (2006). “Dammed Emotions.” The Week (pp. 34-37). April 30.

Prasad, K. (2001). “Indian Tradition of Ecological Protection and Religion.” Man and Development (Vol. XXIII, No.4, pp64-75).

Sangvai, S. (2000). The River and Life: People’s struggle in the Narmada Valley. Mumbai: Earth Care Books (see for a history of the Narmada Bachao Andolan).

Sharma, V.D. (1999). “Bishnois: An Eco-religion.” The Hindu Survey of the Environment. Chennai: The Hindu.

The Hindu. (2004, March 28). “Q& A: Medha Patkar”, retrieved August 9, 2007, from http://

www.hinduonnet.com/2004/03/28/stories/2004032800971300.htm

Vadakumchery, J. (1993) “The Earth Mother and the Indigenous People of India.” Journal of

Dharma (Vol. XVIII, No1.pp 85-97).

Venkateswaran, S.(1995). Environment, Development and the Gender Gap, New Delhi: Sage.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.