by Claudia C. Lodia

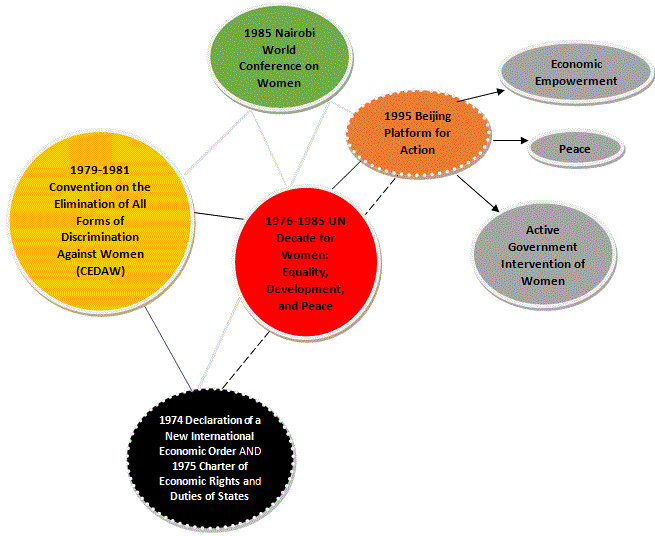

Soon after the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action (BPFA), a platform that reflects the consensus to reassert the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)  while aiming to implement the Nairobi Forward Looking Strategies, women groups on the ground in the global South, began to increasingly illustrate the practical links between women and economic growth, women and peace, and women and active governance. In the past decade, for instance, there has been significant push with the use of affirmative action in Latin America and South Africa as means toward reaching gender equality in representative politics. Additionally, in relation to international peace and security, the women's movement behind the BPFA spurred the passing of the UNSCR 1325, which formally recognizes the utmost importance of a gendered perspective in achieving and maintaining peace.

while aiming to implement the Nairobi Forward Looking Strategies, women groups on the ground in the global South, began to increasingly illustrate the practical links between women and economic growth, women and peace, and women and active governance. In the past decade, for instance, there has been significant push with the use of affirmative action in Latin America and South Africa as means toward reaching gender equality in representative politics. Additionally, in relation to international peace and security, the women's movement behind the BPFA spurred the passing of the UNSCR 1325, which formally recognizes the utmost importance of a gendered perspective in achieving and maintaining peace.

Despite these deployments of gender empowerment, what has become today a rallying point for some women activists is the role of women in promoting and sustaining economic security. It is true there has been an increase of women's visibility and impact on public governance (see Somera, Goetz, and Sobritchea). Yet it is also true that little attention has been made in fast-tracking and actually translating the significance of women in parliament into concrete, measurable, and substantive outcomes. Women and children are still the most affected by poverty today. And this, for the most part, is due to the very structure from and with which economics is done. The issue is then, identifying economic structures that work specifically towards the advancement of the well-being of women and children in the global South, while providing solid potential to claims of livelihood and global human rights.

As activist-economist Devaki Jain states, "there needs to be a reordering of the paradigm of economic reasoning." A redefining of gender equality in terms of women's economic security that recuperates the ambitions behind the now-dead Declaration of a New International Economic Order proposed in 1974. In other words, if there is to be a meaningful implementation of the BPFA's concern around Women and Economy, women in all positions must feel empowered to go beyond what Jain terms as the "macroeconomic skies," that is, the economic model that is systematically and globally enforced as "the standard" for determining the economic growth of all nations, both in the global South and North. Partly echoing Jain's stance can be seen in the 2014 joint statement of Women's Rights Civil Society Movements at the Asia-Pacific Civil Society Consultation for the 20-year Review of the implementation of the BPFA. They, too, recommend the "democratization of economic access to and decision-making of women over economic resources;" "an enforcement of legalities and standards on minimum wage for women, specifically within the Economic and Social Commission for Asian and the Pacific (ESCAP) region;" and "an explicit accounting of the value of subsistence in macroeconomic accounting and policies."

At the heart of the discourse on Women and Economy is whether or not macroeconomics ultimately causes women's poverty, which in turn reproduces the devaluing of women and women's participation in all other aspects of social reality. If we can agree to this, then we can ask further: What conditions give rise to the hegemonic control of macroeconomics? Can we substantively transform the current imbalance of economic power by simply demanding for macroeconomic policies to be "consistent" with gender equality goals? Wouldn't we reach a more transformative change if gender equality goals determined economic policies and not the other way around? In any case, what seems vital and perhaps helpful in grappling with these questions is, recognizing the fluidity of the feminist movement and its relation to the participation of all women from different subject positions – a South-to-South co-production of knowledge among all women. To transgress economic policies built upon patriarchal systems is, in a way, to charter new courses of feminist economic discourse. As Carolyn Sobritchea puts it: "We don't need biological females to fight for women's rights. We want gender sensitive feminists and women's advocates." By calling on other women contributors and advocates – young, old, lesbian, queer, trans woman, able-bodied, or disabled – who are willing to denaturalize the current sexist division of labor, we can co-create a space that helps build on each other's imagined alternative economies. This kind of collaboration where experiences of being-woman are nurtured albeit different from one's own, can contribute to a more gender-responsive conceptualization and implementation of substantive equality, between and among ways of living, today.

Claudia C. Lodia is a Pinay lesbian scholar-activist and a doctoral student of Anthropology and Social Change at California Institute of Integral Studies. She currently volunteers with international feminist organization, Isis International.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.