The last few years have seen the emergence of India as a rising geo-political player from the South, along with China and Brazil. It has also become an information technology hub, that its own National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM) has gained so much prominence among business and technology circles beyond Indian borders.

Yet India remains a country that is perennially coping with scorching poverty and its caste system. Many of its women continue to weather a flood of responsibilities, stormy marriages and relationships, and droughts on access to various resources, including those which would have been warranted by the full exercise of citizenship. They have yet to see themselves in the nationalist and “southern” articulations of their country nor in the economies out of modern communication systems.

For the women in Assam, their capacities and desires to communicate are points of struggle which are continually being re-discovered, nurtured, and lived.

Away in Assam

For the Indian focus group discussion (FGD) of PC4D, the grassroots women working with the Northeast Network (NEN) were selected to further discuss women’s choices of communication tools and their notions of empowerment in relation to pieces of information and communications processes. Jyoti Patil of the Aaalochana Centre for Documentation and Research on Women described the FGD as “a kind of informal discussion and a very effective exercise, where women could understand what they are doing unknowingly. We never looked at communications this way. Now we understand the impact of film, street play, and others.”

Located in Assam, NEN advocates women’s human rights, reproductive health and rights as well as natural resource management through education, capacity-building, and networking, among others. A remote northeast province, bordered by Bhutan and Bangladesh, Assam is host to various indigenous peoples, some of whom have found much association with Eastern Asia. While such diversity has produced a tapestry of cultural and artistic forms and practices, it has been used as a source of conflict between the Indian military and separatist movements.

Women and their communities have managed to live with the intermittent fighting and skirmishes, engaging themselves in farming and weaving. Most of them are located in the remotest parts of Assam, some 95 kilometers away from the nearest phone booths in the urban centres.

Aalochana Centre for Documentation and Research on Women

Aalochana means critical review. The organisation is Pune’s premier women’s documentation and research centre. It was founded by a group of five feminists who are very active in women’s movements. The Centre creates a women’s information hub by providing a variety of resources and information at one place. Aalochana’s vision is to work towards the creation of a gendered, just and democratic society, based on equality and freedom for all castes and classes. For achieving this, Aalochana has committed to the creation of awareness amongst women about their rights and what they can do to change their lives. The organisation’s goals include systematically collecting and providing information on issues related to social, economic, political, legal as well as personal aspects of women’s lives, disseminating the results of research and documentation through pamphlets, booklets, films, slides, lectures, seminars and workshops, and providing a congenial forum where activists, researchers, students, journalists and others can meet and discuss matters of common concern.

From the outset, it is clear why new information and communications technologies (ICTs) such as computers and the internet are likewise a rarity, if not an impossibility for most women and communities. Internet services in the computer kiosks in the urban centres are still exorbitant, costing some Rp. 90 (US$2.03) per hour, compared to internet rates in the more cosmopolitan cities such as Mumbai and New Delhi, Rp. 10 (US$0.23) per hour.

Access to television is likewise limited as some parts of Assam still lack electricity. For some towns which are able to operate television sets, television has somehow reinforced alienation. “Information is there (on TV) but we have seen it from outside, not from inside, and we can only have a partial view,” pointed out by one of the women.

Radio remains the next best thing for those living in the outskirts of Assam because aside from its cheap cost and wide coverage, it does not disrupt the routine of women both in their homes and work. As another FGD participant explained, “They do have radio, in which case, one only needs to listen. Therefore there is no need to have a special time. The work is carried on while listening to the radio. It means a lot.”

Creative Cultural Communications

The inadequate infrastructure of Assam is not thoroughly a barrier against women’s empowerment through communications. In their communities’ isolation, the women have turned themselves to culture and eventually found redeeming communication tools.

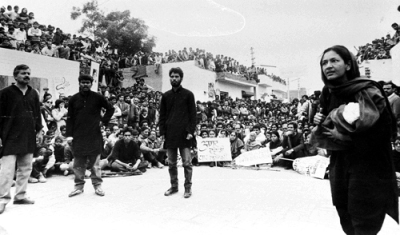

Theatre and puppetry have been so entrenched in the culture, long before the British occupancy, that they have become communal practices. But aside from being an opportunity for celebrations especially when these plays and puppet shows are made parts of festivals, theatre and puppetry have also become liberating forms for women and social movements.

For decades, the medium have been used to educate communities on social struggles and ignite them into action. The same process occurs when intermediary groups bring the theatre and puppets to the streets, closer to the women whose physical mobility has been limited by the gender roles society has imposed on them.

For decades, the medium have been used to educate communities on social struggles and ignite them into action. The same process occurs when intermediary groups bring the theatre and puppets to the streets, closer to the women whose physical mobility has been limited by the gender roles society has imposed on them.

After staging a street play on violence against women, one FGD participant recounted, “The street play can get the message across more than a lecture or a meeting…There were many Adivasi women because Dhekiajuli town is surrounded by tea gardens. These women were weeping. Seeing them crying, I realised that the street play was able to touch the heart of the viewers.”

Patil also related, “Theatre has more impact among the participants. It is the most attractive and accessible because of its language. Films are usually in English or Hindi. Showing them to the village is difficult as it will require dubbing. Theatre does not require much. The culture of Assam has lots of theatre. It fact, this has become a part of their social movements. Women participate in the harvest and other chores, which can easily be expressed in theatre.”

On many occasions, women themselves join in the plays as actors and voices. Discussions are usually done after every play or puppet show, an opportunity for women to share their common concerns. Sometimes these discussions also provide opportunity for women to dialogue with men.

Aside from violence against women, some street plays and puppet shows have dared to discuss otherwise sensitive issues such as early marriages, involving adolescents. These shows have been well-received.

Plays and puppet shows are likewise found to be liberating for people, especially women born of a lower caste. Nautanki, a performing group which Hindu historical accounts relegate to the lowly Bediya caste, have been included by Alarippu, a New Delhi-based activist threatre group, in their work. Nautanki has performed in various women’s colleges, altering certain plays by giving them a feminist portrayal of women, plots, and ending.

Nautanki consists of many talented women. However whenever the group sets up Kothas in the cities, many of these women are lured by upper classmen who leave them pregnant. On many occasions, the women have found themselves in the sex industries.

Some Special Spaces

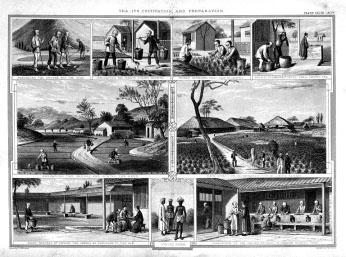

While the women of Assam have found street theatre and puppet shows effective and empowering, they still affirmed the irreplaceability of oral and face-to-face communications between and among grassroots women and intermediary groups. And for meaningful conversations to happen, the women have identified special spaces. Among these are nondescript tea stalls, where women may discuss various issues over cups of tea and baskets of tea leaves. Assam is one of the country’s leading producers of tea since the colonial years.

Nomads have also earned the communities’ trust and enthusiasm, whenever the former would arrive in town at certain times of the year. Caravans would not only bring wares but libraries, letters, and information.

People have also adapted technology according to their culture and resources. But these are located in otherwise privileged spaces that most women, owing to their social positions have yet to find meaning and empowerment in these technologies.

The phone booth, for example, functions as a repository of messages particularly during the monsoon, when roads are impassable. Users who happen to receive calls meant for people in the interior would pick up and leave messages inside the booth — which will only be claimed as soon as the rain stops.

Two FGD participants have also managed to use the internet in urban centres, communicating with other members and staff of NEN. But these women were only able to venture out and use this new technology in the company of their sons.

“I am really touched by the communications strategy of the grassroots women. It is an enriching experience for me. People have their own ways and strategies of communicating, adapting even the new technologies according to their culture,” Patil said.

However, she admitted that it will take a while before new technologies can be effective to women living in the remote parts of Assam.

“For women, creating your own information, your own music for instance and hearing this song is very meaningful. Such is a great confidence booster,” Patil added.

At the moment, it is important to the women of Assam to see themselves in the plays near their own households. It is more empowering to make characters out of themselves, tell their own stories, and create their destinies.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.