Editorial

Why “Feminism Without Borders”1 Matters?

Transcending national boundaries, the Feminist Dialogues (FD) <http://feministdialogues.isiswomen.org/> organised within the World Social Forum since 2003, is a project towards strengthening the feminist movements’ strategies to organise and resist, or even reverse the blows of globalisation.

For 2007, the objective of the Feminist Dialogues was to develop a deep and profound critique of democracy that will enable its transformation and radicalisation, in collaboration and partnership with other social movements. The meeting articulated a plural and radical conception of democracy that recovers the diversity of experiences and conceptions of democracy which are located outside the neo-liberal hegemonic model2.

Implicit in these conceptions and proposals is the democratisation of feminist and social movements themselves.

Even if the understanding of movements is more fluid, and is full of diversities and contradictions, the FD project is a critical juncture of re-thinking, re-invigorating, alliance building and solidarity building. This self-reflexive space has provided us, feminists, an opportunity to work on a transnational movements level and creatively and radically address the backlash and challenges to feminisms that have also grown exponentially with the rise and dominance of neo-liberal capitalism and the consolidation of ethnic nationalist, and of religious fundamentalist movements and nation-states.

In this issue of WIA, we bring you the feminist proposals on radicalising democracy that were presented at the FD 2007 meeting. Further, the articles and the photo essay demonstrate why and how transnational movement building or “feminism without borders” matter in the struggles of economic and social justice in the 21st century.

I’ll leave you with Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s framework on “feminism without borders,” where she calls for feminists to:

- acknowledge the faultlines, conflicts, differences, fears, and containment that borders represents;

- acknowledge that there is no one sense of a border, that the line between and through nations, races, classes, sexualities, religions and disabilities are real and that a feminism without borders must envision change and social justice work across these lines of demarcation and division;

- speak of feminism without silences and exclusions in order to draw attention to the tension between simultaneous plurality and narrowness of borders and the emancipatory potential of crossing through with and over and over these borders in everyday lives; and

- outline a notion of feminist solidarity as opposed to vague assumptions of sisterhood.

In sisterhood!

Raijeli Nicole

Footnotes

1 Mohanty, C. (2004). Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

2 Feminist Dialogues 2007 Concept Note: Feminist Perspectives on Radical Democracy

Democracy: Ruptures and Transformations

In a panel titled “Transforming Democracies” (Transformando las democracias) during the 3rd Feminist Dialogues last January 2007 in Nairobi, Virginia Vargas defined the feminist political position while reflecting on the different forms of democracy.

We have three basic thrusts that we are going to develop. First is to recover the complexities of democracy, not only as a system of government but as a system of social organisation at various levels—in the material level as much as in the symbolic, public as much as in the private, global as much as in the local.

Second,to develop a criticism of actually existing democracies in relation to the ways democratic nationalities are constructed or restrained, and the forms in which various types of political regimes (neo-liberal, militarist and fundamentalist) are nourished, in the state level as well as in the global level.

And finally, to regain the processes of radicalisation of democratic notions of freedom, equality, self-determination and autonomy, and how this radicalisation can be expressed in terms of redistribution of wealth and common goods. In other words, to try to discern these notions of democracy that will move forward proposals of justice at the economic and the cultural levels, at the symbolic and the political levels.

The first thing that I want to put in place is where we are coming from as feminists. We all know that there are many feminisms. I speak from a specific position that considers feminism in its theoretical dimension as well as in its political practice. It is a kind of feminism that develops a critical thinking about current realities and a questioning praxis of sexual and social compromises that exist. It involves analysing and acting on the discrimination of women in permanent confrontation and dispute against other forms of social domination and discrimination. That is to say, we are fighting not only for women but in conjunction with other significant formations that we need to truly transform our society, and truly make another world possible.

At this level, this feminist position has developed substantial ruptures and transgressions that have helped in the reinvention of ways of thinking and acting about the tensions between the sexes or relationships in society. The feminist proposition in which we find ourselves nurtures a new way of looking at the world and a new political culture. It generates new forms of interpretation, new frameworks of making sense of reality. It tries to articulate strategies of social movements, creating projects oriented towards overcoming all forms of exploitation, discrimination and domination. Above all, it tries to confront three predominant forces that exclude, violate and hold humanity in subjection: the forces of neo-liberalism, militarism and fundamentalism.

What we face is dramatically different from what we lived in a few decades ago including the last century, because we are not just facing a time of intense change, we are facing a change of times. A change of times, as it should be, is like the discovery of the wheel or the industrial revolution during its time. It is a change that involves change from industrial capitalism to globalised capitalism, hyper-concentrated but at the same time non-territorialised; changes that are, so to speak, no longer for states alone, but for the entire planet. These changes are developing at a planetary level because of new technologies, but they are also slowly producing multiple resistances against hegemonic forces.

We are in an unjust society, a society at risk because of an economic model that favors the market over people and the economy over politics. We face challenges from conservative societies and fundamentalists, but at the same time live a lifestyle of speed and intensity greater than before, with new social practices that hint at paradigms that are at this moment already in construction and that nurture new reflections.

There is a permanent ambivalence in this process because everything that we had known are many times not useful anymore, and everything that we need, we have just started to construct. For example, when we talk about a society at risk, we can look at it with all its contradiction, for example, a different conscience from what we used to have. A conscience about a planet at risk and about the scarcity of water in the near future, a conscience about the ozone layer and about the injustice in the redistribution of wealth, which feeds at the same time a confluence of actors—social and political—organised around each one of these dimensions.

But at the same time that it produces these social movements, it transforms traditional customs, conservative notions and “common sense”. For example, the changes that have brought about globalisation also opens the door for the necessity of certainties, the necessity of knowing in what world we are in and what we can do within it. This spurs us to see in ways we did not see before—in relation to the suffering of people from the fundamentalisms that are attacking women with tremendous force, fundamentalisms that are not just religious or financial, but are also cultural.

Precisely because new social practices and new subjectivities develop that coexist with anti-democratic practices and grassroots subjectivities, we can admit that we are facing a historical tension between the forces of regulation and the forces of emancipation.

Although this process has left the division of labour of the sexes untouched as a form of organisation of society, it is evident that the continuing impoverishment of women is totally a function of neo-liberal capitalism. The dominant neo-liberal policies lead to an increase in women’s workload, to women assuming duties which the states do not carry out because of privatisation processes. At the same time that neo-liberal capitalism has produced changes that seem irreversible—people have become much more willing to accept new ideas—notions of autonomy, of freedom, of equality—and they start to change their perceptions of these things as people subject to laws.

Precisely because new social practices and new subjectivities develop that coexist with anti-democratic practices and grassroots subjectivities, we can admit that we are facing a historical tension between the forces of regulation and the forces of emancipation. This tension is expressed at the present moment as a tension between a hegemonic, neo-liberal, exclusive, anti-democratic globalisation and an alter-globalisation that constructs elements and dimensions for a democratic globalisation confronting old paradigms and the old and new forms of exclusion.

We also face the change of other certainties. The paradigm of gender has changed dramatically because it was constructed within a capitalist system specifically with the ideology of the man as provider and salaried family man, the woman as domestic worker. Today, the women have politicised the private space and the man as provider exist no more. He is unemployed, the families have become varied in form and we, women, feel much more deserving of rights than we did before. In many more spaces inside many more movements, we find this assertion of rights in indigenous women’s movements, in black women’s movements, in movements for sexual diversity. And this has brought about a dimension, or new definitions of what is feminist because it has modified the view of the difference between the sexes.

We also face the change of other certainties. The paradigm of gender has changed dramatically because it was constructed within a capitalist system specifically with the ideology of the man as provider and salaried family man, the woman as domestic worker. Today, the women have politicised the private space and the man as provider exist no more. He is unemployed, the families have become varied in form and we, women, feel much more deserving of rights than we did before. In many more spaces inside many more movements, we find this assertion of rights in indigenous women’s movements, in black women’s movements, in movements for sexual diversity. And this has brought about a dimension, or new definitions of what is feminist because it has modified the view of the difference between the sexes.

There is a huge questioning, together with the continuing questioning of discriminatory practices, a questioning also inside feminism of heterosexism and of racism, of economic injustice and of colonialism. These are risks which we, feminists, also face when we do not have a more complex view of reality. A substantial change in this process has been the change in the concept of gender. The concept of gender is not anymore a binary opposition between women and men, but a much more nuanced view and complex assessment of the multiple and different identities and discriminations that we, women, suffer. This view also seeks to incorporate other gender identities such as those of transvestites, the transgendered, the inter-sexed, who simply did not exist before in the ideology of global transformations. This has been one of the biggest theoretical contributions of the feminists and the sexual diversity movements: not simplifying views but seeing reality in all its complexity, and opening new dimensions of emancipation.

All these changing views, including all those within the feminisms, urge us to start to question much more strongly our practices and theories that have nurtured us until this time. This is a very important thing because during times of intense change, times in which we live, theory generally serves us little. Practice moves forward much faster than theory. That is why the revision of practice is a fundamental dimension of this process.

I have been involved in a permanent revision in the categories and concepts of organisation of community life and of the institutions that regulate this community life. A concept in permanent dispute for transformative content and meanings has been the concept of democracy. It is because of this that we, women at this moment in these feminist dialogues, have assumed as a political-theoretical framework for the concept of radical democracy.

On the one hand, formal democracy has resulted in enormous achievements that we have had—in laws and civic knowledge throughout the planet for all women. But with the difficulties we face with fundamentalists, with regressions, among others, this formal democracy has also in many ways condemned women to their invisibility. It has fed capitalism and has given in to capitalist functionality, which means giving primacy to private interests, to hegemonic fighters in hegemonic countries, at the expense of militant communities and the environment. It has tried to regulate the bodies and sexualities of women, all in the name of democracy.

On the one hand, formal democracy has resulted in enormous achievements that we have had—in laws and civic knowledge throughout the planet for all women. But with the difficulties we face with fundamentalists, with regressions, among others, this formal democracy has also in many ways condemned women to their invisibility. It has fed capitalism and has given in to capitalist functionality, which means giving primacy to private interests, to hegemonic fighters in hegemonic countries, at the expense of militant communities and the environment. It has tried to regulate the bodies and sexualities of women, all in the name of democracy.

We as feminists do not want an authoritarian state; neither do we want a tutelary state. We do not want a state where community norms, religion, or a political party decides for us. Neither do we want a socialist state that makes everything uniform and fails to recognise other exclusions, such as social classes.

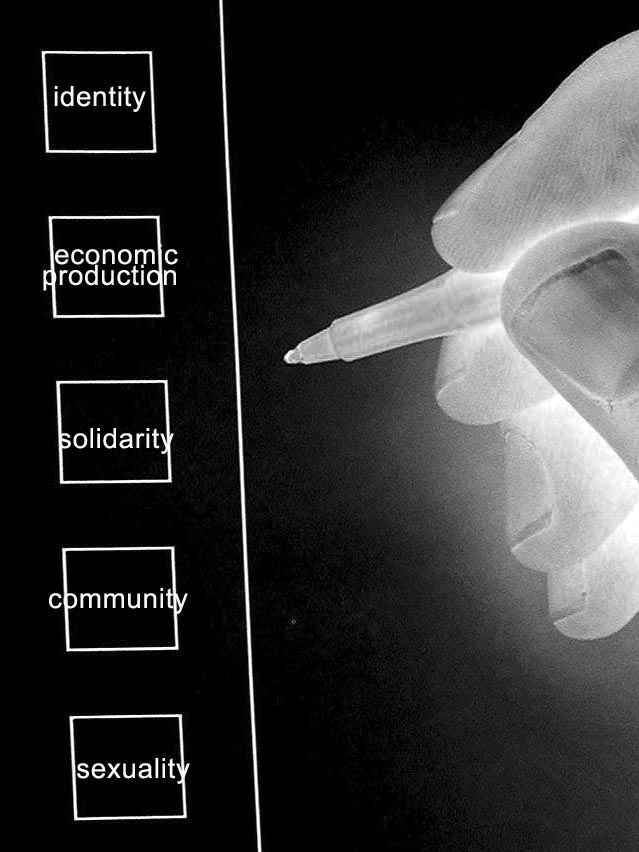

...for us, feminists, one of the challenges of this radical conception of democracy is to understand the relationships between sexuality, production, and reproduction as material dimensions and symbolic of the social relationships of exploitation and as alternatives to the simultaneousness of the causes.

We have an extraordinary slogan, “Democracy in the country and in the house!” This, of course, we understand as including what is intimate in all relationships. But this democracy in all spaces also takes in other authors like, for example, La Aventura (The Adventure) of Sosa Santos. Sosa Santos talks of six structural spaces from which one constructs a new political, democratic culture in the domestic space with the struggle for a self-determined sexual identity, the fight against violence against women and for new kinds of families, the fight for diverse sexual identities and for the recognition of domestic work, the fight for the recognition of reproductive work. The space of production has given a foothold to a great quantity of movements surrounding economic solidarity, alternative economies, new kinds of organisation of labour, the spaces of the market community of citizens and of the global space.

I think that for us, feminists, one of the challenges of this radical conception of democracy is to understand the relationships between sexuality, production, and reproduction as material dimensions and symbolic of the social relationships of exploitation and as alternatives to the simultaneousness of the causes.

The end has to do with the people. These causes and these new actors change the politics of the sense of justice, extending to it the relationships of gender to the environment, to economic redistribution, to the sexual dimension, to the racial dimension, confronting the states to raise new civic dimensions. That is how, at this moment, for example, we can talk about the sexual dimension of the people—that we did not use to have but that we already have in our conscience—from the ecological dimension of the population, or from the global dimension of the people that confronts the nation-state, that confronts the phenomenon of migration of the population and the recognition of civic rights, that at this moment had been limited to the national states.

Finally, democratising democracy has, as its ethical sustenance, the transformation of power in shared authority as much within our movements as in the larger society and our relationships with the states. This is a political and epistemological challenge; it is another way of assuming power and another process of acquiring it. Shared authority, for example, between civil society and the state, between political parties and social movements, between the social movements themselves, and inside the feminisms themselves, is another democratic utopia, as de Oliveira says in her article, “The challenge that we have before us is to transform ourselves as a movement and at the same time change the world.”

This paper, originally in Spanish was presented at the 3rd Feminist Dialogues, 17-19 January 2007, Nairobi, Kenya. This was translated to English by Ma. Camila Venezuela for Isis International-Manila.

“Where we stand in the struggle” - New Feminist

Strategies in a Illustration Neo-liberal World

The first protest against neo-liberal globalisation that I attended was the demonstration against the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in Seattle in 1999. I had gone with a group of young Southern feminists and feminists of colour from my university. We met a group of young activists of colour from the Bay Area in California, joined them in their preparations, and eventually marched with them. The experience taught me two important lessons.

The Bay Area activists knew that if the police began to attack, the racist US police force would, of course, target the activists of colour first, and probably target us with more violence. And if that happened, we would need to know what our rights were regarding arrest, and have the phone number of a lawyer ready. We grouped ourselves into pairs and kept track of each other in the demonstration to ensure that no one was hurt. When the state security began its violent onslaught with tanks, we found our way to safety while other protesters threw themselves at the police. In the end, none of us was seriously injured and no one was arrested.

And so I learned the first lesson—in resisting, you can never forget your identity in history—as a woman, as a person from the South, as a minority in the North. Who you are always determines how you experience violation. Acknowledging this is the first step in finding appropriate tools for resistance and sustaining the struggle.

When the police began to fire rubber bullets at the protesters we were, of course, afraid, and decided to regroup and assess what to do next. We huddled together and one of the brothers asked, “Has anyone seen people being hit by a rubber bullet?” We all replied affirmatively. “Has anyone been hit by one?” One person raised a hand. He asked, “What did it feel like?” The person responded, “Well, it stung a bit, like being slapped.” “So it won’t seriously injure or kill you?” he asked. “No,” the person replied. “So then we have nothing to be scared of!” he responded.

From that exchange, I learned the second lesson—you have to invest in understanding what you are opposing, so that you have an accurate sense of its weaknesses, its strengths, and the difference between its perceived and actual power.

With those two thoughts in mind, I would like to focus on some of the key trends which I feel are imperative to take note of and develop strategies around, and then make a few suggestions for the way forward.

Recognising new constellations of power and resources

I would like to draw attention to an additional trend which is posing a complicated challenge to us as feminists—that of the growth of private, philanthropic entrepreneurs. As individuals, they have no formal accountability to the public and fall even further below the radar of international law than corporations.The concept paper on radical democracy prepared for the Feminist Dialogues cites the new and growing forms of power that are undermining our freedoms as women, and as citizens. It brings out, in particular, the fact that the business of transnational corporations and the aid from international banks and governments come with political baggage and often with “strings” that undermine the sovereignty and authority of the state in the global South.

While not ignoring this, I would like to draw attention to an additional trend which is posing a complicated challenge to us as feminists—that of the growth of private, philanthropic entrepreneurs. As individuals, they have no formal accountability to the public and fall even further below the radar of international law than corporations.

Take the most visible philanthropist of the twenty-first century, Bill Gates. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has an endowment fund of $66 billion, an amount a recent Los Angeles Times’ article estimates to be greater than the gross domestic product (GDP) of 70% of the world’s nations. At present, the majority of this endowment is invested unethically in the lucrative oil industry, an industry intimately linked to militarism and environmental abuses, both of which women pay a heavy price for. The agenda of the Gates Foundation’s actual philanthropy also has a considerable- and potentially transformatory- leverage around global policy on health. And yet, Southern citizens have no platform to engage with the program or investment policies of either the individual or his foundation.

Another example is the Sudanese mobile phone entrepreneur, Mo Ibrahim. Ibrahim is the owner of Celtel, the official mobile service provider for the Nairobi World Social Forum. His recently created The Mo Ibrahim Award for Achievement in African Leadership promotes “democracy” by awarding a multi-million dollar cash prize to an African leader that has demonstrated good governance on leaving office. The prize fundamentally undermines the idea that it is the duty of elected representatives to be fair and non-corrupt, and replaces accountability to the voting public with a cash incentive. His initiative has been lauded by the international political elite, despite the glaring slap in the face for the concept of democratic accountability.

We urgently need more feminist funding research to track the agendas of the large streams of private money being invested in the South, and identify ways to intervene to make this financing more accountable to needs and rights as articulated by affected communities.

My point here is not to criticise all forms of individual philanthropy. The role and effects of private philanthropy are far from uniform, and progressive philanthropy remains important in keeping feminist NGOs and human rights activism alive. Rather, we must acknowledge the fact that development financing is no longer a question of government to government, bank to government, or even industry to government deals. We urgently need more feminist funding research to track the agendas of the large streams of private money being invested in the South, and identify ways to intervene to make this financing more accountable to needs and rights as articulated by affected communities. Again, a nuanced understanding of the new constellations of power we face is vital for turning them in our favour.

A second trend to track is the rapid growth of Southern economies and the implications this will have for economic and social policy decisions in the next fifty years. India, China, South Africa and Brazil are all gaining a stronger foothold in global markets, and as a consequence, in global politics and decision-making. While there may well be progressive civil societies in these countries, including active feminist movements, this does not necessarily translate into progressive government policies at the national level or in the international domain, particularly with regard to women’s rights. (The Brazilian government under Lula has demonstrated progressive leadership on HIV/AIDS and anti-homophobia internationally, although this is always vulnerable to political trade-offs when it has the potential to impact negatively on trade.) Given this, I would argue that we need a more variegated analysis of “South” and “North.” I return to my opening lesson of acknowledging who we are in history as a beginning point for effective activism. The world for my generation cannot be so easily split into binary political geographies or solely into a struggle of “us versus them.”

Moving forward

One of the African sisters, Stella Mukasa, made a call for us to start being more concrete in our suggestions, and to move from “opposing” to “proposing.” Reflecting on the notion of radical democracy, what would a feminist constitution look like? How would it enable young women’s participation and voice?

How do we use our collective power base to push the feminist agenda forward? For while we do spend a considerable amount of time identifying and assessing our vulnerabilities, we also have a strong power base—the power of our numbers as half the world’s population, our collective intellectual power as feminists, our power as voters and as consumers—and use this as the basis for catalyzing change and holding our abusers to account.

Whatever happened to the concept of self-determination? It is a concept that I learned in the teachings of Gandhi and Nyerere, among others, thinking about the predicament of dependency in the global economy. It is a concept that I rarely hear debated in Southern feminist forums or in the discourse of my fellow young feminists. If we do not want to be reliant on the products of a highly inequitable global market economy, how do we generate alternatives? How active are we in the research and practice of alternative agriculture and energy, for example?

Turning the focus to this forum, we have had such trouble communicating with each other across language barriers. Perhaps one activist investment we can make as feminists working transnationally is to develop our language skills. There are now training institutes for young feminists; how about creating a feminist language institute? Individuals may commit to begin to learn the major international languages—French, Spanish, English, Arabic—and could then attend a month-long intensive language training, taught by feminists, where they can develop their ability to speak, read, and write and also learn feminist terminology in these new languages. We know that while our interpreters do a great job, they are often not exposed to feminist terminology, hence, they can translate our presentations incorrectly. What about collectively developing a feminist lexicon for our interpreters and translators to use?

To end, Nelson Mandela has been criticised in some quarters for upholding idealistic principles of justice and equity. To this, he responds that his moral compass is not guided by idealism but democratic realism.

This process of the Feminist Dialogues and the project of (re)defining the parameters of justice and democracy are critical for us as young women. We have inherited a world of increasing inequity and injustice, but I am inspired by the faith that another world—a feminist world—is possible. Let us invest in developing our visions and strategies of feminist democratic realism!

Jessica Horn is a feminist activist and poet with roots in Uganda and the USA. She currently works for a human rights funder in London and is active in the African Feminist Forum.

Jessica Horn is a feminist activist and poet with roots in Uganda and the USA. She currently works for a human rights funder in London and is active in the African Feminist Forum.

This paper was presented at the 3rd Feminist Dialogues, 17-19 January 2007, Nairobi, Kenya.

Fiesta Feminista in Malaysia

Fiesta Feminista in Malaysia

Malaysia’s feminists are now setting the stage for a “Fiesta Feminista” to be held on June 15-17, 2007. The event aims to bring in women to discuss issues on feminism, human rights, and democracy in the country. Prior to this, Isis International-Manila had the chance to virtually solicit the insights of the Fiesta Feminista Organising Committee on this event.

Isis International-Manila [Isis]: Could you share with us what Fiesta Feminista is all about? How was this event conceptualised? What are its objectives? Who are your intended participants?

Fiesta Feminista Organising Comittee [FFOC]: Approximately a year ago, in conjunction with International Women’s Day, the Women’s Development Collective (WDC) organised a talk titled, “Reflections and Challenges of the Women’s Movement.” Out of this surfaced the idea of a regular nationwide women’s meeting in Malaysia, similar to those held in other parts of the world (e.g., the Latin American Feminist Encounters, Indian National Women’s Conference) which have allowed women, activists, and feminists to successfully exchange ideas, strategise, and extend solidarity with one another. This, it was felt, was an opportune time when the local women’s movement faced increasing challenges in terms of organising and addressing issues of inequality and discrimination. It was also deemed an opportunity for movement-building purposes. The idea had been contemplated in the past, but was not pursued for lack of resources and different priorities.

Another important motivation was the socio-political climate in the country. Despite a change in government leadership and its efforts to foster greater transparency and accountability, Malaysia still lacked a democratic space in which ordinary Malaysians can claim their basic human rights. This situation has been aggravated by the practice of ethnicised politics, and the growing backlash of religious conservatism that affects women disproportionately, particularly with regard women’s sexuality.

Subsequently, WDC proposed organising this event in collaboration with other members of the Joint Action Group for Gender Equality (JAG). JAG is a coalition of progressive women’s groups, many of whom have been working together since the mid-1980s. It comprises of the All Women’s Action Society (AWAM), Sisters in Islam (SIS), Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO), Women’s Centre for Change, Penang (WCC) and the Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC) - Women’s Committee and WDC.

Later, this collaboration extended to include the Gender Studies Programme of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Universiti Malaya (UM), Kuala Lumpur. This joint effort between JAG and the Gender Studies Programme of UM marks the first time these two key players in civil society—women’s groups and academia, will join efforts to address common issues facing Malaysian women. The synergy that is expected to come out of this will pave the way to narrow the gap between these two actors, and hopefully, between theory and practice.

Following a series of discussions, it was decided that this national event would be known as Fiesta Feminista, and take place at the university campus from 15-17 June 2007. The broad objectives of Fiesta Feminista are:

• To put feminism in the forefront and popularise it in Malaysia so that anyone who is interested in learning more about inequalities and injustice in society—particularly between women and men—and who want to actively change this situation, has an avenue to do so;

• To bring together a broad range of people, women in particular, to discuss challenges, exchange ideas, evaluate, and strategise around issues of feminism, human rights, and democracy in Malaysia;

• To create a space in which the next generation of feminist leaders in Malaysia can participate and take charge. Hopefully, the occasion will also be a leadership building activity and contribute to facilitating an effective transition between the current and future leaders of the women’s movement.

Invited to this event are primarily women (but also some men) who recognise the inequalities that exist in our society, and who want to actively do something to change this. Pursuing our desire to see participants from a diverse range of backgrounds, we have identified several groups of community-based women, half of whom will come from outside the Klang Valley (i.e., the most populous and urban area of the country), and are working to specifically mobilise their involvement at Fiesta Feminista.

These women were identified through the networks that JAG members have built over the last 25 years. These different groups include plantation women from the rural areas; kindergarten teachers from poor communities outside the Klang Valley; indigenous women from both the peninsular and east Malaysia; women urban settlers (squatters); single mothers and disabled women. Special attention is being given to mobilising younger women, grassroots communities, as well as other groups of women through whom forefronting and popularising feminism—can be brought to new places.

This event is not intended as a one-time effort but rather something held once every two to three years. For this year, WDC will serve as the event’s secretariat.

This event is not intended as a one-time effort but rather something held once every two to three years. For this year, WDC will serve as the event’s secretariat.

Isis: What is the theme of this event? What are the topics or issues to be discussed?

FFOC: “Embracing Diversity” is this year’s theme. In line with efforts to draw women from different identities and backgrounds, we hope Fiesta Feminista will serve as a platform where diversity can be recognised, negotiated, respected and celebrated. The term diversity not only signifies the diversity that exists among women, but also the diversity among religious and ethnic groups, classes, ages, sexualities, locations and organisations. It also refers to the diversity of issues, questions and challenges that will be raised.

This two-and-a-half-day event will see a range of activities never before seen—structured discussions in the form of panel presentations and dialogue sessions; skills building and strategising workshops; open space activities and film screenings. All these will come under four tracks:

• Feminism, gender and development;

• Human rights and democracy;

• Social movements; and

• Women organising.

Fiesta Feminista organising is guided by principles that have been collectively agreed upon by the Organising Committee. This will ensure that messages that come out during the event do not promote patriarchal, fundamentalist, racist or ethnocentric notions nor support neo-liberal policies. The organisers also wish to ensure that the event is environmentally-friendly.

we realised that we would be bringing in a diverse group of women and men, in terms of language, class, location, etc. Thus, we felt it was especially important to adopt approaches that would enhance everyone’s participation and involvement in Fiesta Feminista. Isis: Being a “Fiesta,” what approaches would you utilise to facilitate discussions and dialogues?

FFOC: This was one of the first things the Organising Committee discussed because we realised that we would be bringing in a diverse group of women and men, in terms of language, class, location, etc. Thus, we felt it was especially important to adopt approaches that would enhance everyone’s participation and involvement in Fiesta Feminista.

For instance, as many of us know, plenary sessions usually involve invited speakers sharing their thoughts on the main themes of an event. However, often only a handful of people from the floor will be able to engage them and respond to what is being shared because there is seldom time for a meaningful exchange of ideas, between the invited speakers and those from the floor. Thus, we have proposed that the two main plenary sessions of Fiesta Feminista be followed by discussions in smaller breakout groups which will be facilitated in a such a way that maximises audience involvement. This will provide more people a better chance to share their responses or thoughts to the main ideas from the plenary.

By pitching the structured discussion sessions at three levels—basic, intermediate and advanced—we hope we can make the discussions as relevant to as many people as possible, and thereby facilitate more effective communication. As far as possible, both English and Bahasa Malaysia will be used as the medium of communication. Where necessary, whisper translation will also be provided in Mandarin and Tamil. We hope this will allow us to overcome the language barrier, which in many situations can impede the input of certain groups.

We are also aware of how creativity can be a bridge between different groups of women. Hence, apart from sessions where people talk and listen, there are also sessions where they can participate through non-verbal means or hands-on activities. We will have activities such as poster exhibitions, street theatre, as well as the screening of films by local independent film directors followed by open discussions with the directors themselves. Suffice it to say that, in general, we are trying to ensure that there is creativity and innovation in as many activities as possible, such that participants will feel at ease sharing their thoughts on issues being raised, even those that might be considered contentious.

Because we have space limitations, given that we expect around 400 participants plus another 100 or so volunteers, we have also discussed the need to enable more than those attending, to reflect and learn about feminism as well. Consequently, outside of the event, we will conduct a media campaign running up to Fiesta Feminista, which will include covering the event’s activities. The challenge, however, is reaching out to non-English speaking and rural-based Malaysians. To bring ideas of feminism to places where feminism has never been discussed, it will be important for us to work with the vernacular media.

The fact that it has taken us this long to organise an event like Fiesta Feminista, the first public activity which highlights and showcases feminism, is perhaps revealing of the nature and political spectrum of the women’s movement in Malaysia. Isis: In terms of the nature of the women’s movement in Malaysia and its political spectrum, how would you describe it? Could you share its brief history?

FFOC: The fact that it has taken us this long to organise an event like Fiesta Feminista, the first public activity which highlights and showcases feminism, is perhaps revealing of the nature and political spectrum of the women’s movement in Malaysia. The contemporary movement can be broadly divided into three categories of women’s organisations: one comprising those predominantly concerned with women’s welfare needs; another involving groups that have been built on issues around violence against women; and the third, a much smaller category consisting of those wanting to address issues of women, democracy, and human rights. It has only been in the last five years or so that more organisations—particularly those that traditionally have dealt with violence against women concerns—have expanded their definition of “women’s issues” to include women’s human rights.

Even so, the whole topic of feminism has been and remains a difficult one. While many individual activists may subscribe to this ideology, much fewer are willing to be publicly associated with it simply because of the immense negative connotations as well as fear of backlash and ostracism. In that sense, organising Fiesta Feminista is groundbreaking. It provides an avenue for us to demystify feminism and demonstrate that this is not something alien, that there have always been women in Malaysia who have believed in the cause of women’s equality and also been concerned with larger social justice issues beyond traditional “women’s issues.”

Isis: What are your expected outcomes? How could Feminist Fiesta aid in strengthening alliances among feminist movements and in advancing feminist issues in Malaysia?

FFOC: One of the main challenges is getting more Malaysians from all walks of life interested and involved in the women’s movement’s causes and activities. Over the last 25 years, women’s groups have successfully raised public awareness and pushed for legal reforms in the areas of violence against women. Despite this, the numbers of those advocating for women’s equality remain small. It is, therefore, hoped that Fiesta Feminista will be a movement-building exercise that not only consolidates existing strengths within the women’s movement, but also can attract new energies and diversity into its fold, and through this, introduce new ways of learning and doing feminism.

One important coalition building activity will be the inter-movement dialogues with groups such as the sexually- marginalised and workers’ organisations, two important social actors with whom we seek to build better alliances. In so doing, we wish also to uncover and examine existing assumptions, inquire and learn about their issues and perhaps even come to a shared understanding. We plan to strengthen our own understanding of issues such as ethnic relations and abortion, which have not been adequately grasped or discussed by most in the women’s movement. To strengthen linkages with feminists from the region, we will also be inviting some of them to share their insights and experiences from their own countries so we can learn and reflect on these.

While these are our hopes for Fiesta Feminista, we are also trying to be realistic and are more than aware of the many challenges that lie ahead. We do not know exactly what the outcome will be but the fact that many have responded positively is clearly a good start. We are prepared to make this a huge learning experience, one on which we intend to build future collaborations. We want Fiesta Feminista to contribute significantly to the growth of feminism and the women’s movement in Malaysia.

Editor’s Note:

While the One on One section is envisaged as an interview with an identified personality, the Fiesta Feminista Organising Committee however opted to talk to Isis as a group.

In memory of the victims of Christian fundamentalism

A copper sculpture titled, “In the Name of God,” was inaugurated on 1 December 2006, International AIDS Day, in front of the cathedral of Copenhagen. The sculpture depicts a pregnant teenage girl crucified on a high cross. The sculpture is an outcry, an artist’s comment on the crusade against contraception and denial of sexual rights launched by Christian fundamentalists, with President Bush and the Roman Catholic Pope in the lead. The exhibit, carried out in cooperation with Dean Anders Gadegaard and the parish council, quickly sparked a lively debate in the press and the Internet (see http://www.aidoh.dk/debate).

The life-sized Copenhagen sculpture is the first in a series of similar sculptures to be displayed worldwide. Although it is not meant as a contribution to the abortion debate, its aim is to advocate for the right to contraception and to truthful and unprejudiced sexual education. The sponsors of the event believe that the promotion of such rights is shared by wide circles of people, independent of their stance on abortion.

The concept behind the work of art

Other versions of the crucified pregnant girl will be cast in copper. Some versions are naked. Others have clothes covering intimate parts of the body, to avoid a futile dispute about nudity that in some countries might derail the debate. The sculpture can be displayed in different ways. It can be mounted on a cross or made to stand on tiptoe on a plinth. The height of the cross can vary, from 2.5 to 5 metres, according to the space at the exhibit site.

A big colour photo of the crucified teenager on the front page, with the title of the sculpture and the subtitle, “In memory of the victims of fundamentalism,” has been made into a poster. On the rear side of the poster are printed basic facts about the consequences of fundamentalist interference in projects carried out by contraception clinics.

The sculpture and the poster will be useful in various ways:

- The display of the sculpture in its different versions will trigger and fuel discussions about contraception, sex-phobia and Christian fundamentalists’ ban on condoms.

- The poster will be issued in big numbers (70,000 copies) and distributed the world over to relevant NGOs. These will be encouraged to display the poster and create a ripple effect so that thousands of other small art exhibitions will spur more discussions. The press will also be invited to publish the poster.

- Forty thousand flyers will be printed with the same motif as the A3-size poster, with a thorough explanation of the project and links to sculptural sites.

Events can be followed at: <http://www.aidoh.dk/InTheNameOfGod>

A comprehensive documentation and a wide range of linkages on the HIV/AIDS situation can be found at: <http://www.aidoh.dk/GlobalGag>

Sites of exhibition

In Denmark, the art installation in front of the Cathedral of Copenhagen will be on tour in Nairobi, London, Texas and the Vatican. At the opening, Dean Anders Gadegaard declared it is important for Danish Christians to take some responsibility on the issue and express an opinion about what “their” God is being used for globally.

In Nairobi, Kenya, the sculpture was displayed at the World Social Forum (WSF) 20-25 January 2007, where 100,000 people came. It is appropriate that the WSF took place in the heart of Africa, exactly where the contraception discussions had been most intense. The event also projected the sculpture globally.

A big women’s association that has its roots in Africa had considered exhibiting the sculpture in London on 8 March, International Women’s Day.

In Italy, the sculpture will be displayed in St. Peter’s Square in Rome and will later be exhibited at a gallery in central Rome.

In Texas, the sculpture will be launched in coordination with liberal Christian groups and various NGOs.

Other sites to be considered include Poland and the European Union (EU) Parliament.

Partners

The project expects to cooperate with the following:

• Artists and art institutions who are interested in seeing art come out of the museums, rather than be constrained within them, and to challenge opinions on real-life issues in the public domain.

• Progressive Christians who are not interested in “their” God being taken prisoner by a right wing conservative interpretation of the Bible, with disastrous consequences.

• Organisations working worldwide with HIV/AIDS and contraception policies, as well as organisations defending women’s rights.

Symbolism

The sculpture is a rich symbol that can generate multi-layered interpretations. Here are just some possible meanings that can be attributed to the work of art:

• As a symbol of Christianity, the cross is immediately associated with the Christian faith. Because of a fundamentalist interpretation, a shift in contraception policy has been enforced in many places in the world. The consequences have been disastrous, especially in Africa.

• The cross is an ancient execution device, a brutal method for killing. In Africa, a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS is often synonymous with receiving a death sentence.

• Crucifixion was a public and protracted mode of execution, an agony that could last several days. Likewise, the death process of the HIV-contaminated is protracted and painful. The sexual offence is tabooed, hence, extramarital pregnancy often leads to social exclusion and stigmatisation (in the cross, this is represented by the piercing of Jesus’ hands and feet).

• The pregnant teenager symbolises innocence, with rich associations of Jesus as an innocent sacrificial lamb. The child who has been led astray because of ignorance, impulsiveness or maybe as a rape victim, is mercilessly exposed to the ultimate punishment, as Jesus was.

The female body symbolises women as bearers of the brunt of suffering. • The female body symbolises women as bearers of the brunt of suffering. Unlike the male body, they display the proof of the sexual act. Often, the woman has become HIV-contaminated through rape or through contact with a husband who has engaged and been HIV-infected in an extra-marital intercourse.

Blasphemy?

The cross is a very strong symbol, so I face the risk that the sculpture will provoke passionate reactions. Many people may be outraged and even see it as blasphemous.

But by no means is it intended to be blasphemous. When a parallel is drawn from Jesus’ suffering on the cross to the suffering of women in our time, we envisage a modern interpretation of the compassionate Jesus. His suffering and death on the cross was an expression of endless compassion and solidarity with humanity. Jesus himself makes a connection between people’s suffering and his own through the statement, “I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40). The quotation spurs us to take Jesus seriously in a modern context. This is exactly what the sculpture does as a living symbol, expressing compassion with those who are suffering.

This sculptural outcry is aimed at a religious interpretation that causes suffering and hardships to the world’s most vulnerable people, not a criticism of Christianity as such. Should the powerful language of art not be allowed to show the crucified Jesus taking the side of the present day’s suffering and oppressed, then the narrative of the Gospel will at best be reduced to a barren ceremony void of connection to the world we live in. At worst, the Gospel will be instrumentalised to legitimise a policy causing suffering and death to millions. In fact, I think that this abuse of God and the Bible deserves the term “blasphemous.”

This sculptural outcry is aimed at a religious interpretation that causes suffering and hardships to the world’s most vulnerable people, not a criticism of Christianity as such. The artist appreciates cooperation with Christian groups that take Christian charity seriously, and accordingly, take the side of the suffering. Such an attitude is an expression of a Christian tradition that asserts a commitment to relieve suffering. A research into church history reveals a multitude of monasteries and hospitals, connected to the Catholic Church or other Churches, displaying readiness to help the sick and poor, when all others had failed.

Factual background

Recently, the fundamentalists, with President Bush and the Roman Catholic Pope in the lead, have dominated the discussion about AIDS and contraception. The disastrous consequence has been the withdrawal of funds from contraception programs carried out by the UN and NGOs the world over.

The fundamentalists assert that handing out condoms and giving information on contraception is an invitation and instigation to promiscuity. They claim that people should be taught not to have sex before marriage, and when married, to use sex only for procreation.

This policy has created disasters where it has been introduced. For ten years, Uganda succeeded in reducing the spread of HIV contamination through massive campaigns to use condoms and to limit the number of sexual partners. Condoms were handed out for free. As a result, the rate of contamination has decreased from 15% of the population in 1990 to 5% in 2001. But in 2002, Uganda changed its policy. Pressured by the US President, Uganda removed the condoms from the campaign, and sexual abstinence was extolled as the only means to fight HIV. The result has been the doubling of new contaminations each year from 70,000 in 2003 to 130,000 in 2005.

As a result of the implementation of the same policy, Texas is one of the states with the highest per capita number of HIV-contaminated in the USA and the highest number of teenage pregnancies.

This article, originally found on <www.aidoh.dk/new-struct/Happenings- and-Projects/2006/In-the-Name-of-God/

GB-In-the-Name-of-God.htm>, is reprinted with permission from the author.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.