Rural Women and Natural Resources in Nepal:Women’s Roles in Survival versus Hegemonies

The use of natural resources is essential to everyone and is a basic human needs especially to those living in rural environments. For people denied such access, life is a matter of survival, many survive at the cost of extreme dependence on those who have access.

The use of natural resources is essential to everyone and is a basic human needs especially to those living in rural environments. For people denied such access, life is a matter of survival, many survive at the cost of extreme dependence on those who have access.

The fourfold caste divisions are Brahman (priest and scholars), Kshatriya or Chhetri (rulers and warriors), Vaisya (or Vaisaya, merchants and traders), Sudra (farmers, artisans, and labourers). Caste determines an individual’s bahavior, obligations, and expectations. All the social, economic, religious, legal, and political activities of a caste society are prescibed by sanctions that determine and limit access to land, position of political power, and command of human labour.

Source: http://countrystudies.us/ nepal/31.htmSuch is the case of Nepal, a landlocked country located between China (north) and India (south, east, west). It has a population of 28,901,790 (July 2007 est.) and a total land area of 147,181 square kilometres.1 While Nepal consists of unlimited natural resources such as water, timber, hydropower, and scenic beauty, it has an extremely fragile environment. It is often affected by severe flooding, landslides, and famine and faces environmental problems such as deforestation because of an overuse of wood for fuel. These often have negative impacts on people in rural areas who depend highly on nature for their survival. It must be noted that the majority of people, especially those in the rural areas, depend on land and agriculture as an economic activity.

Because patriarchal ideologies and religious laws prevail in Nepal, dimensions of identity such as gender, caste, and ethnicity create hegemonic privilege on the use of natural resources.

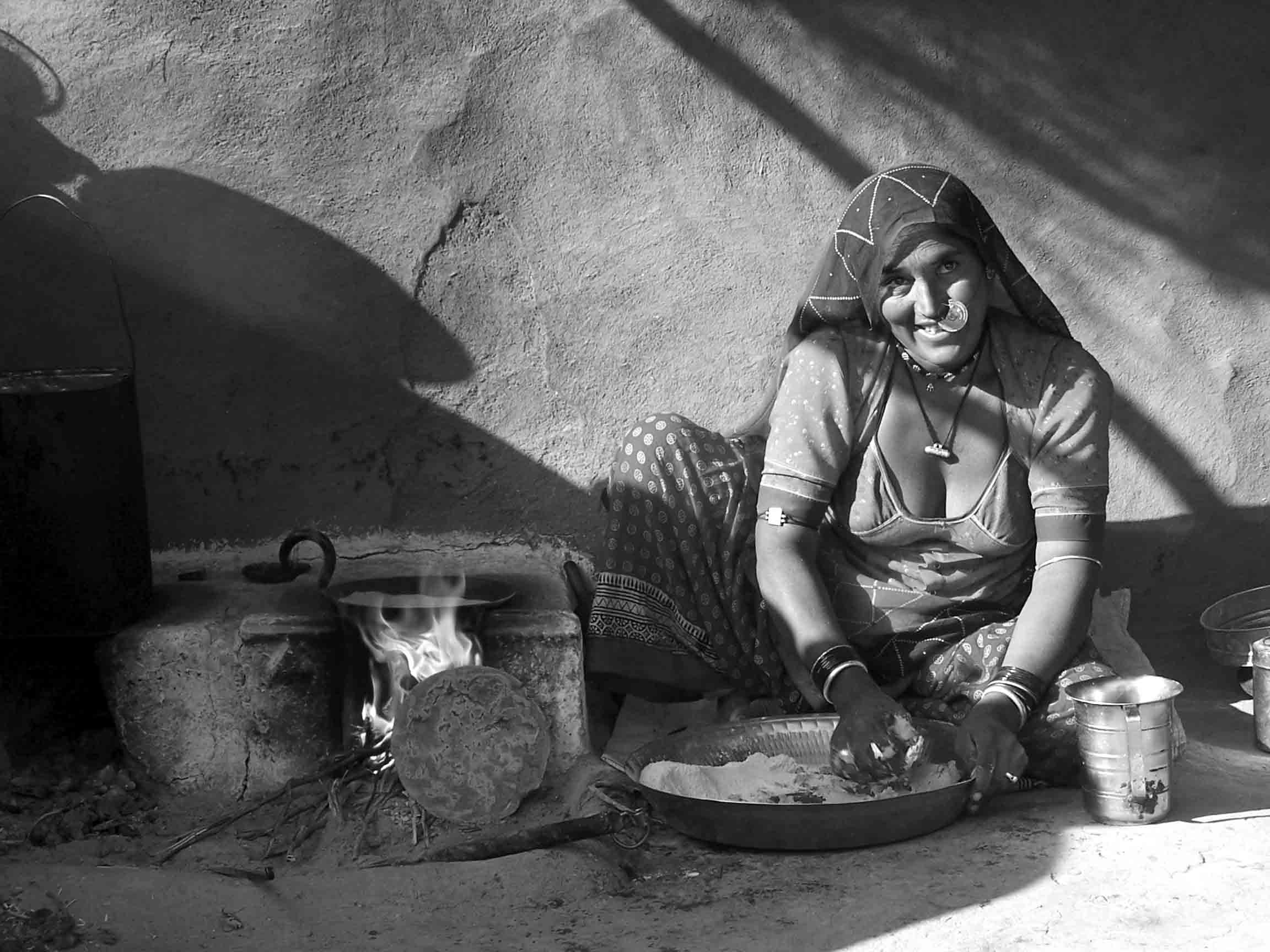

Practices based on religion and patriarchy inevitably play a role in maintaining social inequalities. The dominant religion is Hinduism which stratifies castes into four: the Brahmin as the highest, Kshatri, Vaisya, and Shudra or Dalit as the lowest/untouchables. Practices leading to gender inequality such as the unequal division of labour based on the patriarchal tradition puts women to work in domestic (reproductive) sphere and men to work in the public (productive) sphere. While women are engaged in completing household chores, bearing and rearing children, taking care of the elderly, providing water and food to family, men often work outside the home—mostly in skilled jobs and/or income generating activities.

Hegemony

The predominant influence, as of state, region, or group, over another or others.

Source: www.dictionary.comBecause patriarchal ideologies and religious laws prevail in Nepal, dimensions of identity such as gender, caste, and ethnicity create hegemonic privilege on the use of natural resources. This paper aims to draw attention to the hegemonic politics at the micro level pertaining to the access to natural resources from the women’s perspective, and to come up with recommendations. The paper will present examples of how Nepalese rural women ensure their family’s survival as they play a vital role in the provision of water and food.

Customary and legal framework

The patriarchal custom of preferring sons over daughters (a discrimination and deprivation on the basis of sex/gender) starts immediately after birth.

...a weak and restricted legal framework is not better or worse than the cultural regulatory framework which denies inheritance of properties and land rights to women. They only reinforce patriarchy as these laws are biased and male-centred.

The right to inheritance and access to property and land are denied to women while the inheritance to son is claimed as a son’s birthright. Although a legal bill has been passed as a government initiative in 1997 declaring daughters as co-heirs of the parental properties including land, it has certain biases such as only daughters who remain unmarried until the age of 35 (which represents half of their life since the average Nepalese woman’s life span is 57.1 years),2 can inherit parental properties or land. If they marry later on, then they are to return the properties to their maternal relatives. On the other hand, those who are married have equal right to the ancestral property or land of their husband’s side if their husbands are not alive provided that they are 35 years of age or married for at least 15 years. Such a weak and restricted legal framework is not better or worse than the cultural regulatory framework which denies inheritance of properties and land rights to women. They only reinforce patriarchy as these laws are biased and male-centred.

The Hindu caste system custom stratifies Brahmins (highest caste) as high profile people and Dalits (lowest caste) as low profile people. The latter are called pani nachalne jaat (caste from whom water is not accepted) and the water touched by them is considered polluted and unusable; whoever comes into contact with them needs purification. This makes it difficult for Dalits to get access to water-wells and other public natural resources.

The Hindu caste system custom stratifies Brahmins (highest caste) as high profile people and Dalits (lowest caste) as low profile people. The latter are called pani nachalne jaat (caste from whom water is not accepted) and the water touched by them is considered polluted and unusable; whoever comes into contact with them needs purification. This makes it difficult for Dalits to get access to water-wells and other public natural resources.

Nepal’s Constitution of 1990 states that no discrimination shall be made against any citizen on grounds of religion, race, sex, caste, tribe or ideological conviction. Following this, in August 2001, the Nepalese Government said, “it would outlaw discrimination against lower-caste Hindus and ... pass a law ending the centuries-old system that deems certain people untouchable.”3 Although from time to time such mandatory is passed, they haven’t as yet proved effective.

Family survival lies on deprived women’s shoulders

Nepalese rural women (especially those in the far western region, northern hilly regions, and terai region) are poor and disadvantaged due to lack of access to education and income as well as lack of rights to land and property.

In poor families, girl children are rarely sent to school while parents somehow manage to send their boy children. Whatever parental property the family has is inherited by sons; it is seen as their birthright and their right as caretaker of parents in their old age. Daughters have no such privilege to inheritance; they are perceived to be burdens who are to be married off. They are instead provided only with a dowry (money and gifts) which in many cases are later possessed by the husband and his family. Although girl children belonging to economically stable families get schooling opportunities during their childhood, they too are forced to marry and leave the house when they grow up. Although they receive a higher amount of dowry compared to poor family’s daughters, still they lack rights to equal inheritance of parental properties; hence, their economic status remains low in the household of the husband. Such customary practices find their roots from Nepal’s religious and patriarchal culture.

In poor families, girl children are rarely sent to school while parents somehow manage to send their boy children. Whatever parental property the family has is inherited by sons; it is seen as their birthright and their right as caretaker of parents in their old age. Daughters have no such privilege to inheritance; they are perceived to be burdens who are to be married off. They are instead provided only with a dowry (money and gifts) which in many cases are later possessed by the husband and his family. Although girl children belonging to economically stable families get schooling opportunities during their childhood, they too are forced to marry and leave the house when they grow up. Although they receive a higher amount of dowry compared to poor family’s daughters, still they lack rights to equal inheritance of parental properties; hence, their economic status remains low in the household of the husband. Such customary practices find their roots from Nepal’s religious and patriarchal culture.

Women, from childhood until marriage and later age, depend on male members (father, brother, husband, and son) of their household who have access to all economic sources. Yet, it is these women who play an important role in ensuring the family’s physical survival. They walk miles through the forests and mountains in search of water and firewood, jeopardising their health. A study by Kumar and Hotchkiss (1988)4 indicates that during times of high deforestation, women’s time needed to collect one load of fuel wood increases by seventy-five percent. This gives them less time for themselves and to engage in other productive activities. They also fall ill and suffer from various diseases, abortion, etc. as they walk, in the hazardous forest areas over the hills and on the slippery roads, sometimes barefoot. Fuel wood shortage further intensifies women’s deprivation as they save on fuel and eat less. It is also known that women eat least, and last.5

Hegemonic religious laws and the water crisis

Women’s physical and mental suffering worsen when there is shortage of water. Women belonging to the Dalit caste are denied access to water from communities where upper castes such as Brahmins reside. In some cases they are even tortured if they try to get water from Brahmin areas. These extreme cases can be seen in Nepal’s rural areas where privileged (hegemonic) groups (identified by caste, ethnicity or class) often play unethical roles— under-privileging and denying certain others access to public natural resources. Water wells are sometimes privatised by the so-called upper castes, this then becomes a question of survival for Dalits. Women being the providers of water to their families, often become victims and suffer not only from a violation of rights but also from torture and violence.

Although such challenges put women’s well-being at risk, so far, Nepalese women have not compromised and have continuously worked to secure their family’s well-being. Women denied access to water wells look for other options such as traveling a long way to forests and hills in search of spring water. Currently, some women have even courageously filed cases against the violators, thus challenging the caste system.6 Although from time to time women have showed resistance to discriminative practices through protests and demonstrations and demanded their fundamental human rights, events have not turned in their favour as, overall, society is still male-dominated. On the macro level, policies and laws are made without addressing social inequalities and hegemonic power relations.

Hegemonic patriarchal ideologies limit women’s access to land

Although from time to time women have showed resistance to discriminative practices through protests and demonstrations and demanded their fundamental human rights, events have not turned in their favour as, overall, society is still male-dominated.

Landlessness is the cause of acute poverty in Nepal where the majority depends on agriculture for food production. The first government initiative (1951) and several more programmes, later on land reform, tended to abolish the unequal shares of excessive land ownership by distributing equal shares to landless and poor farmers in rural areas. However, this has brought about another for m of unequal ownership, where family male members claimed ownership; those lands became their family properties and passed on to sons, excluding women. Such patriarchal customs continue to deny women inheritance and property and land rights. The government initiative, lacking in gender analysis, ignored gender-based needs in agriculture and access to land and thus has been very ineffective till this day. This is seen as biased and weak.7

Ninety percent of private lands are owned by men while women own only ten percent.8 Although statistics show women own about ten percent of land, it can be assumed that these women either come from urban liberal families or simply are widows who inherited their husband’s land. Since women cannot decide on family land use, it becomes difficult for women especially those in the rural areas to think of planting trees in their own lands and making use of them instead of using the forest resources, which are heavily used for survival purposes and are fast becoming extinct.

Further concerns on women’s access to natural resources

Women not only physically and mentally suffer from unequal power relations but their long travels in sourcing and fetching water makes it difficult for them to get involved in productive activities such as adult education and income generation.

Hence, it is assumed that women unknowingly cause the depletion of forests due to less education and information. Women’s excessive use of marginal natural resources tends to enforce the cycle of environmental degradation and poverty.9 Women cut down trees from forests and hillocks to meet their cooking needs. As a result, the forest springs disappear, and the cycle of deforestation and environmental degradation continues.

Are women doing so due to lack of knowledge of environmental ethics? Or is it simply because the forest trees are the only resource available to them? Although the consequence is that women themselves suffer, as they have to walk far in search of drinking water, the devastating outcomes—among them ecological deterioration, deforestation, shortage of water and fuel woods—are brought about not only because of ignorance but also because of limited circumstances. Women have no other options available to replace forest woods, unlike other societies where people enjoy conveniences like solar stoves, and most of all, ownership of lands. Because the actual problem is never studied from the women’s perspective, projects that include women in natural resource management are not effective in the long run.

Are women doing so due to lack of knowledge of environmental ethics? Or is it simply because the forest trees are the only resource available to them? Although the consequence is that women themselves suffer, as they have to walk far in search of drinking water, the devastating outcomes—among them ecological deterioration, deforestation, shortage of water and fuel woods—are brought about not only because of ignorance but also because of limited circumstances. Women have no other options available to replace forest woods, unlike other societies where people enjoy conveniences like solar stoves, and most of all, ownership of lands. Because the actual problem is never studied from the women’s perspective, projects that include women in natural resource management are not effective in the long run.

Women are family protectors, need listening ears

Although the sexual division of labour, which assigns women to work in the domestic sphere and take care of the family’s physical needs, and assigns men to work in the public sphere and take care of the family’s economic needs, women ensure their family’s survival by facing various challenges. These challenges in providing food and water many times put women at risk but they still manage to protect other people’s lives. They often endure the situation continuously, even without any support from family or community. Hence, women’s strength as the family protector may seem mysterious and legendary but this comes from their

ability to manage natural resources. This acquires greater importance in rural fragile environments.

Considerable attention is required from policymakers and planners in natural resource management. Equally important is to revitalise women’s strength so they can challenge the existing hegemonic politics that hinder their well-being. Those working for human rights seek to abolish such inequalities but many times are not able to hear the cries of those who often silently endure pain just to protect their families. Sometimes women are even blamed for making heavy use of natural resources and causing deforestation. Their ignorance is cited but their needs and their dilemmas are not heard.

Attention needed at macro level

he bottom line may be argued thus: since women are the major users and managers of natural resources such as water, forest wood, trees programmes at the macro level must include gender- sensitive analysis of the gender-based needs and roles in people’s access to natural resources.

While undertaking such policies and reforms, women who have been marginalised by hegemonic politics as well as weak legal regulatory framework and customs (including the caste system, patriarchal ideology, religious laws) should be consulted. They should raise their voices. More females should design legal and policy frameworks, thus avoiding male-centered ones. Women should be given proper training and education on natural resource use and management, thereby reducing the scarcity problems as well as ecological degradation. Women’s vulnerability as well as strengths in securing their family’s survival in the struggle over natural resources need appropriate policies which promote women’s rights.

Endnotes

1 The World Factbook. (2007). https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/np.html.

2 UNFPA. (2000). State of world population.

3 Gurubacharya, B. (2001). Nepal acts to outlaw caste discrimination. London: The Independent.

4 Kumar, S.K. and Hotchkiss, D. (1988). Consequences of deforestation for women’s time allocation, agricultural production, and nutrition in hill areas of Nepal.

5 PRB. (2002). Women, Men and Environmental Change.

6 Jana Uthhan. (2007).

7 Thapa Prem Jung. (2001). The cost-benefit of land reform, Himal South Asian.

8 Neupane, S. (1999). http://www.apwld.org/wrwd_nepal.htm

9 Dankelman, I. (2001). Gender and Environment: Lessons to learn. DAW, ISDR.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.