Politicians and the Shaping of Masculinities: Mr. Gore Goes to Washington

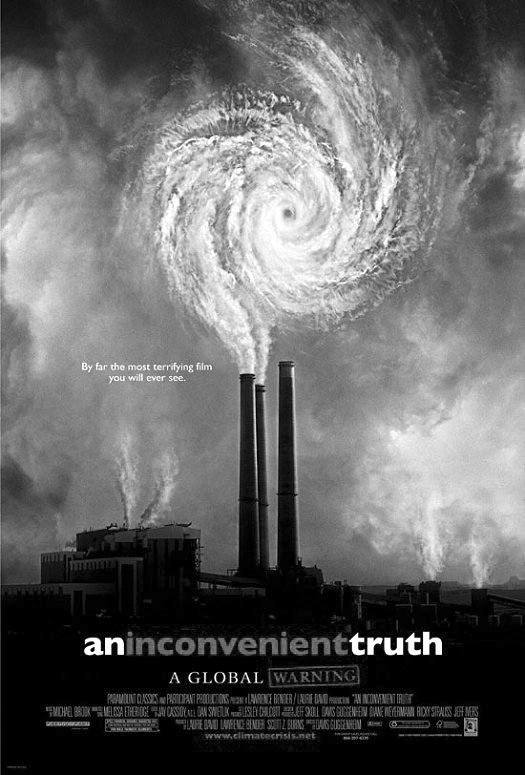

Blending elements of American transcendentalism, political celebrity, and more than just a touch of the apocalyptic “disaster film” genre, Davis Guggenheim’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth struck a chord with U.S. publics upon its release in 2006. The film hit the same cultural zeitgeist that bred Hollywood blockbusters like The Day After Tomorrow, as well as similarly themed documentaries like Laurie Lennard’s H.B.O. film, Too Hot to Handle and Leonardo DiCaprio’s The 11th Hour.

An Inconvenient Truth became one of the top three highest-grossing documentaries of all time (Stanley, 2007). In a kind of counterpoint to the “campaign trail documentary” format, the film follows Al Gore as he tours the country, armed with his Power Point lecture on environmental degradation, his earnest intelligence, and his southern drawl. The film paints a picture of Gore not as a politician, but as the inheritor of a distinct kind of American masculinity.1 In doing so, the film implicitly renders Gore a counterpoint to the brand of masculinity espoused by George W. Bush, his opponent, and as some would argue, usurper in the 2000 U.S. presidential election. While Bush purposefully asserts a kind of cowboy masculinity appropriate for a figure molded in the image of Ronald Reagan, who also used extensive cowboy iconography in the shaping of his persona, 2 Gore’s masculinity is a different brand following something more along the lines of a seasoned Jimmy Stewart, classical Hollywood’s populist hero, than a John Wayne, its warrior prototype.

By depicting these two characters as opposite poles, the film fashions a portrait of an “ideal” American masculinity. Interestingly, both are discursively configured around their relationships with their environment. This configuration mirrors the historic binary created between two archetypal figures in constr uctions of U.S. masculinity: Frederick Jackson Turner and Theodore Roosevelt. As historian Richard Slotkin argues, both men constructed this masculinity in terms of its relationship to the frontier, a mythic space in U.S. imagination and national identity, framed as an Edenic garden by Turner’s agrarianism and as a wilderness by Roosevelt’s “rough riders.” Gore and Bush, Jr. become inheritors of these masculine types.

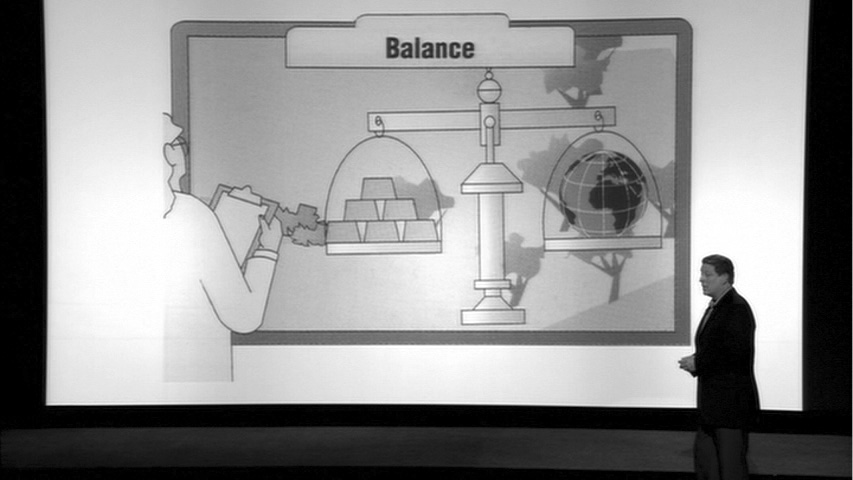

To be sure, the film is about global warming, as the political thriller-style trailers that won its wide viewership assert. It offers culprits: politicians and bureaucrats. It also supplies victims: those in China coping with floods as their neighboring provinces suffer from droughts, New Orleans residents caught in Hurricane Katrina in spite of massive warnings that such a disaster was inevitable. The ultimate victim of Man’s greed is, of course, all of humanity, as demonstrated by Gore’s presentations of satellite photos depicting the Earth as a tiny, barely discernible speck of dust amid a sea of other stars. While the documentary is ostensibly about global warming and impending environmental disaster, the film is also steeped in nostalgia—not simply for some prelapsarian relationship between humanity and nature, but for a lost opportunity for heroic leadership. “Where might the U.S. be, had Gore rightfully assumed his office?” the film implicitly asks. How might the world look if we didn’t view terrorists as a greater threat than rising ocean levels, if we didn’t have an administration that viewed “earth in the balance” as a steady equilibrium between gold bars and the entire globe, as depicted in a previous Bush administration slide displayed at the Earth Summit?

Gore uses the slide to reveal arguments that embody an important misconception surrounding environmentalism: that “we have to choose between the economy and the environment.” Gore’s lone figure beneath the image of this scale, gently poking fun at its absurdity, creates the image of a single man poised against an overwhelmingly damaged political mentality that equates the accumulation of wealth with the fate of humanity. The Earth is a resource, yielding financial, rather than natural resources.

Viewing these resources as commodities opposes the notion that the earth’s resources should provide sustenance— fossil fuels versus far ming, or, industrialism/conquering versus agrarianism/cultivating.

This image of Gore as the lone figure fighting these infrastructures virtually single-handedly follows in a long line of populist heroics depicted in cinema, most commonly in the movies of Frank Capra. For example, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) is the classic “whistleblower” film; Jimmy Stewart plays Jefferson Smith, head of the Boy Rangers, a small-town innocent who comes to Washington bright-eyed only to discover the greed of politicians who have injured the U.S. democratic system. The film depicts this system, of course, in saccharine perfection. It is never the infrastructure that is the problem, it is only the individuals operating within it. Defining the political field as such, it only follows that to solve the greed and corruption of individuals, you simply need more individuals—the heroic, incorruptible kind this time. There’s no necessity for collective action. Furthermore, the archetypical heroic agent within these national narratives is an “Everyman,” the “Common Man,” and every other phrase used to describe the generic citizen: male. There are choices to be made in order to solve inequities, but these choices are between differing kinds of white masculinity, leaving little room for that which falls outside that category (women, racial minorities, etc.) or for femininity. Like Jefferson Smith, the Gore of An Inconvenient Truth is an outsider to Washington politics. He laments:

“It’s extremely frustrating to me to communicate over and over again, as clearly as I can, and we are still, by far, the worst contributor to the problem. I look around and look for really meaningful signs that we’re about to really change, I don’t see it right now.”

The film cuts from Gore’s voicing his frustration to a series of shots of Reagan, then Bush Senior, denying the validity of global warming. Gore is the speaker of truths, and as the title of the film suggests, these truths are inconvenient for those whose priorities are skewed by avarice. Gore is not this kind of man.

This is the underlying message of An Inconvenient Truth, a significant film for its educational value and its ability to win a wide audience, but ultimately, a film carrying a message of reform rather than radical change.

While the film would certainly scoff at the notion of the Lone Ranger, gunslinger for m of masculine leadership, it embraces a kind of masculine leadership embodied in its depiction of Gore. He urges Washington bureaucrats to listen when he presents them with scientific evidence about rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and their relationship to rising temperatures, but they pay no heed. He wanders the globe, traveling from the North and South Poles to the Amazon to learn from scientists who would provide evidence on these issues.

He fulfills the Protestant work ethic by remembering his time on his family’s tobacco farm, a place where he could play in a bucolic utopia, defined against the confinement of urban living. Against a montage of sun-dappled, Tennessee farmland, we hear Gore remembering:

“My childhood was a little unusual in that I would spend eight months of the year in Washington D.C., in a little hotel apartment, and the other four months were spent here, on this big, beautiful farm. I had a dog here, I had a pony here, I could shoot my rifle here, I could go swimming in the river here, go out and lay down in the grass. As a kid, it took me a while to learn the difference between fun and work.”

Gore is the agrarian variation of the masculine ideal. Moreover, he enjoys the “honest work” of manual labour, as opposed to the dull organisational life of governing systems. The film takes pains to distance its hero from governmental systems, from the life of the organisation, and from forms of collective action.

While right wing critics called the film “extreme” and “alarmist,”3 the courses of action the film proposes are moderate, perhaps even apologetic. These courses of action accompany the closing credits, and begin with the question, “Are you ready to change the way you live?” Addressing the viewer and positioning their own, personal lifestyles in relation to the arguments Gore makes, the film asserts, “The climate crisis can be solved, here’s how to start.” The ideas include buying energy efficient appliances, changing your thermostat, and weatherising your house (after all, doing so gets you an energy audit, the film tells us).

These are all useful suggestions, and overall, the film is important in its generation of press coverage and its locating of political action on the terrain of everyday life. However, it remains tied to ideas of the autonomous individual; Al Gore is the model of this kind of ideal citizen. The film’s priority is to inform, rather than incite, and for that, it is a useful tool, albeit one that positions the environment around tropes of American masculinity. That this level of the film’s discourse remained outside the public discussions surrounding it suggests the degree to which such positionings of gender, the environment, leadership, and appropriate forms of action are embedded in public consciousness.

Endnotes

1 For a classic campaign trail documentary, see Robert Drew’s Primary (1960). Another is Alexandra Pelosi’s

coverage of George W. Bush’s campaign trail, Journeys With George (2002).

2 For an assessment of Reaganite masculinity, see Susan Jeffords, Hard Bodies: Hollywood masculinity in the

Reagan Era, Rutgers University Press (1994).

3 Steven Hayward, a Senior Fellow in Environmental Studies at the free-market policy research organisation at

the Pacific Research Institute, even produced a documentary specifically arguing against Gore’s film.

Conservative critics like Fred Barnes at the Weekly Standard claimed, “Hayward…has an advantage over

Gore. Unlike Gore, he is calm and reasonable, avoids hyperbole, and sticks to the facts….”

Page 2 of 2

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.