Six years ago a small group of lifelong activists co-created Engender, a non- government organisation (NGO) based in Cape Town, South Africa. Engender’s founding principles were to engage with consciousness transformation and intersectionalities in the areas of genders and sexualities, justice and peace. In 2006, we won a prestigious inaugural national award from the South African NGO Network (Sangonet) for our website, including its poetry which supports our work: www.engender.org.za

We were determined to transcend hierarchy, to operate on principles of consensus and partnership, to walk our feminist thought and talk. In 2002 and 2003, many thought we were quite mad but a handful thought we were visionary. We avoided Descartian thinking. Instead we set up simple and low-cost projects, designed with and by local women we had collectively engaged with for decades. We started with a one-day workshop, which could be conducted in as few as three hours, depending on the need, and which focused on consciousness transformation.

We were determined to transcend hierarchy, to operate on principles of consensus and partnership, to walk our feminist thought and talk. In 2002 and 2003, many thought we were quite mad but a handful thought we were visionary. We avoided Descartian thinking. Instead we set up simple and low-cost projects, designed with and by local women we had collectively engaged with for decades. We started with a one-day workshop, which could be conducted in as few as three hours, depending on the need, and which focused on consciousness transformation.

Our one-day consciousness raising gender workshop, especially with service providers and community leaders (like local councillors, all with prior gender trainings), elicited the need for further work on women reclaiming our sexualities, our femininities, and perhaps even our own divinity, broadly defined. We discovered that many of us had so vigorously engaged in anti-Apartheid activisms and post- Apartheid nation-building, that we had never spared a thought for reclaiming our bodies, akin to feminist moments in the global North since the late 1960s.

Women leaders here who had received advanced gender training were heard saying that they hated their own bodies, hated menstruation, hated femininity; while simultaneously revering masculinity and the phallus/phallic. Engender responded by offering a one-day workshop, contractible to even two hours if needed, for those who had attended our initial consciousness workshop. These two workshops worked so well, we find more calls for support than we could possibly satisfy.

Of course we simultaneously engaged in a number of intersecting projects, including research and writing and advocacy work. But we feel most passionate about these two initial workshops which defined our founding principles most concretely.

Through our workshops with grassroots communities, including women’s migrant groups and informal settlements (where people live in shanties with little or no state support), we received several pressing requests from women for support on establishing backyard and community gardens.

Women were unaware of South Africa’s formal financial policy, beyond the fact that the government was failing them; the fact that they were without food and other basic resources; and the fact that no one seemed to care about them. They themselves wanted to take charge of their own lives and provide their own food, through these simple gardens.

At the same time, our neoliberal Minister of Finance, Trevor Manual, a former anti- Apartheid activist, urged people to cultivate their own food, due to the rising cost of oil and basic foodstuffs.

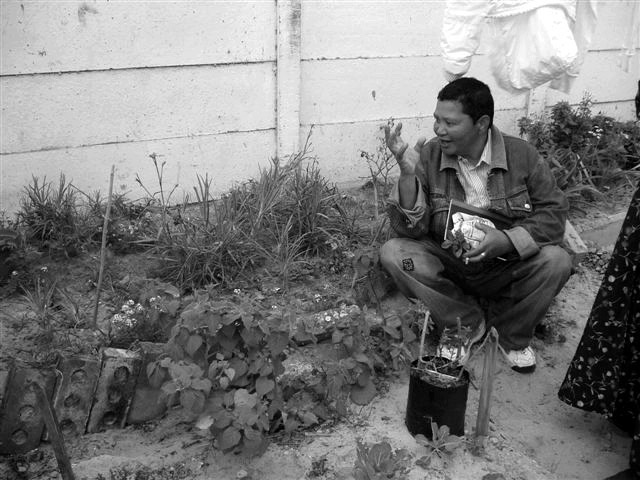

At our request, Biowatch, a local environmental NGO, sent its trainer to Village Heights, an informal settlement near the beaches of Muizenberg. It is always ironic that great wealth and immense poverty can live side by side, the poverty often hidden by dunes or other convenient blind spots. The Biowatch trainer demonstrated one example of a backdoor garden. Bernadette Peters, one of the community women present that day, immediately began replicating this simple model in several other women’s backyards.

Intersectionality

An intersectional approach to analysing the disempowerment of marginalised women attempts to capture the consequences of the interaction between two or more forms of subordination. It addresses the manner in which racism, patriarchy, class oppression and other discriminatory systems create inequalities that structure the relative positions of women, races, ethnicities, classes, and the like. Moreover, intersectionality addresses the way that specific acts and policies operate together to create further disempowerment.

Source: www.cwgl.rutgers.edu

Engender became so impressed with Bernie’s leadership skills and initiative that we started to collaborate very closely with her, and through small grants, offer her a modest monthly allowance, in addition to seeds and small gardening implements. Bernie supports some 200 backyard gardens which serve more than a hundred people in her informal settlement.

We also collaborate with community gardener, Malinda Droomer in Atlantis, the ironically named Apartheid-era township for “coloured” or mulatto people, who are the descendants of the KhoeSan, Southern Africa’s First People.

So too Engender collaborates with Priscilla van Aswegen, who used to live “rough on the streets” of Cape Town, organising other homeless people while on the street and exhibiting generosity typical of the KhoeSan, to even inspire a full-length documentary film, Priscilla vannie Kaap by the Norwegian Siv Oevernes.

Priscilla now lives in the “coloured” township of Mitchells Plain and still practices, within her limited means, the indigenous feminist gift economy, passing surplus squash, potatoes and other vegetables to her more indigent neighbours and selling the rest to support her four children at elementary school.

It is also no accident that the germinator of the Feminist Gift Economy paradigm, Genevieve Vaughan, supports our gardens project in concrete ways. Our gardens coordinators gift their surplus vegetables to their neighbours and sell the rest for cash to purchase essential supplies such as for the schooling of their kids.

Even Engender’s director’s backyard was painstakingly transformed from a typical suburban lawn with pretty flowers into a vibrant indigenous garden, where we grow vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes, herbs like rosemary, lavender and geranium for both culinary and medicinal use.

Even Engender’s director’s backyard was painstakingly transformed from a typical suburban lawn with pretty flowers into a vibrant indigenous garden, where we grow vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes, herbs like rosemary, lavender and geranium for both culinary and medicinal use.

We use all available space and even containers like old bathtubs. Nothing artificial is used on our plants and in our soil. Indigenous scholar- activist, Yvette Abraham and her female partner donated worms for composting from their smallholding an hour outside Cape Town. We are having a bumper tomato crop at present — humungous blood-red tomatoes everywhere, beg ging to be gifted to neighbours, to be eaten with joy.

Thus Engender’s work very much resembles our gardens: it all grows organically. Our work remains intersectional, including the ancient indigenous idea that all things (including people) are inextricably connected in a “web of life,” with no one thing more important than any other. Our work is founded on reclaiming ancient indigenous consciousness, ways of being. Growing our own food is a critical celebration of our connection with the Earth, with the Sky.

The ordinary women in our projects do not know, or care about the differences between ecofeminism, and feminist political ecology. The do not know why our ruling party transformed from a progressive liberation movement to a patriarchal neoliberal state. Our grassroots women merely care about satisfying their basic and other needs, about caring for each other, about the survival of, and a better life for, their children.

As we witness in the most concrete ways imaginable that no two plants or fruits, even from the same species are identical, we know that no two humans, no two women are homogenous, even as we share critical elements like physiology, and vulnerability to gender-based violence like routine rape under Patriarchy.

Like some Quakers, we seek consensus rather than majoritarian r ule. We live in “multiversity”1, aware of all that impacts us, from (capitalist) economics to structural and cultural racisms and genocide, in the traditional feminist understanding of intersectionalities. Since many of us are indigenous to where we find ourselves2. We are also profoundly aware of our intersections with all, within and beyond, “as above so below.”

. Footnotes

1 Susan Hawthorne on her idea of “wild politics”, in ISIS Women in Action, 2007: 2.

2 Europeans too are indigenous - to Europe.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.