Much has been written about the richness and diversity of Kenya, its people and environment ever since the colonial era. To a certain extent, it has come to represent the beauty of Africa and its culture, so timeless that it offers never ending opportunities for discovery and re-discovery. But however abundant Kenya and the rest of Africa are, many of its people remain in the bondage of poverty, hunger and destitution.

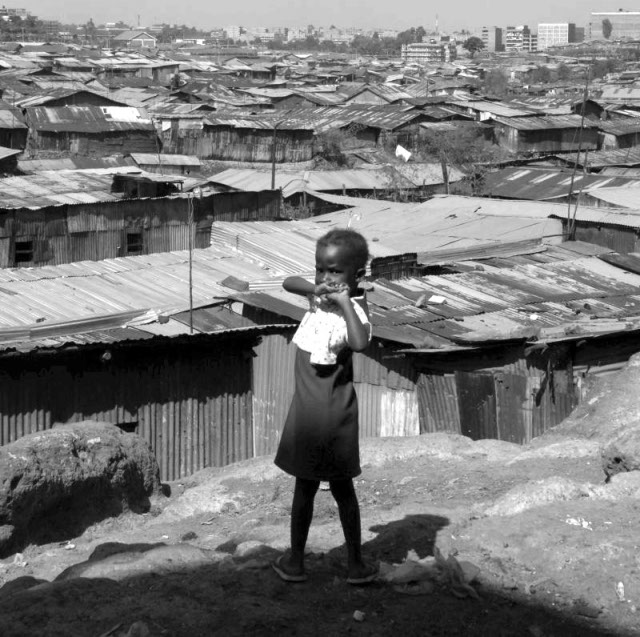

Ioutskirts of Nairobi for in Mathare, at the have been living the last 17 years. Mathare has been known as a slum area and I believe, is the true face of Kenya. Being one of the oldest slums in Africa, its poverty can truly confirm that its people are residing in the valley of death.

The government has long stopped its operations and services in the area some 20 years ago. But even before, the government’s provision of public toilets and maintenance of the sewerage system were quite limited. In fact, these important tasks were a subject of corruption. As soon as they came into their offices, some government employees would report that they cleaned an area, yet nothing had been done to the dilapidated toilets and clogged drainage.

Mathare’s residents would have wanted to take the government into account but the dictatorship then prevented most Kenyans to express dissatisfaction and dissent. So we have learned to live with the situation and in our small ways, have done something about it.

Majority of the adult residents of Mathare are labourers, many of them have found themselves in industrial areas focused on food production. It is ironic that while they prepare and package the neighbouring provinces’ produce such as pineapples, mangoes, oranges, cabbages, pepper and even cut flowers for export, they hardly have enough on their own tables.

The slums have been a source of a huge workforce which toils with quite low salary, so inadequate that it is impossible to save up for one’s own house. A labourer usually receives Kes 4,000 (US$52) a month.

Ungga or maize flour, the country’s staple costs Kes 110 (US$ 1.43) per two kilos, which for a family of five means two suppers. The past several months have been a period of adjustment and sacrifice as prices of basic commodities like ungga soared from Kes 74 (US$0.96) per two kilos to the present Kes 110 (US$1.43) per two kilos. Pork and beef have truly become a sign of prestige, as they are pegged at Kes 300 (US$3.90) and Kes 200 (US$2.60) per kilo respectively. This is why most people have substituted such meat with goat heads and legs whose cost range from Kes 10 (US$0.13) to Kes 30 (US$0.39) per slice. Since the cost of meat is not affordable, the community also opts for rejects.

Kenyan Politics

Kenya has experienced a relatively stable political climate in the past few years. Following the death of Jomo Kenyatta in 1978, the country’s first president, Kenya was ruled by Daniel arap Moi until 2002.

The single party constitution under the presidency of Moi eventually became a cause for unrest, especially among academicians and activists. Cases of political repression and torture soon alienated Kenya, especially with the end of the Cold War, when Western governments sharply criticised Moi. During the 1988 elections, the government introduced a queuing system where voters lined up according to their favoured candidates instead of casting their votes through a secret ballot. With the development of a multi-party coalition, Moi was barred from running in 2002.

In 2002, Mwai Kibaki won the elections against Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Jomo and the annointed candidate of Moi. Kibaki’s second attempt for the presidency in 2007 was marred by controversies and violence. This event led to a power-sharing deal between Kibaki’s Party of National Unity and the opposition party, Orange Democratic Movement.

Sources: Njeri, Juliet. (2 January 2008). “Kibaki: Dream or nightmare?.” ; and Phombeah, Gray. (5 August 2002). “Moi’s legacy to Kenya.”

Photo from “Profile of His Execellency Hon. Mwai Kibaki, CGH, MP, President and Commander -in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kenya.”

The labourers usually save on transportation, as they head to the factories and later, to their homes, walking some seven to 10 kilometers. They are likewise vulnerable to sickness, accidents, death and others, without recourse to any social benefits, much less private insurance. Most of them who are working in agribusiness suffer from ailments associated with their exposure to the factories’ freezing temperatures. Most people have not visited the hospitals and instead, prefering cheap but expired drugs from the quacks in the shacks.

The food crisis has had a profound impact on women who have less access to land and other resources. In Kenya, a woman’s ownership of land only comes through marriage, particularly when the husband dies. But even as the husband may own land, the wife can never be sure of her claims, especially if it is a polygamous marriage.

Also there has been an increasing number of cases of husbands abandoning their families because of the immense burden of providing for the children especially in light of the house rent and school fees.

Aside from being labourers in industrial areas, some women, especially housewives have taken on laundry jobs in the better neighbourhoods in Eastleigh, Huruma and Pangani.

In cases of abandonment, the burden is passed on to women, who would have to bear them on their own. A number has been driven to prostitution and has been exposed to HIV-AIDS. Some women have also resorted to giving up their young daughters for a few coins yet are still trapped within the vicious cycle of early pregnancy and abandonment.

The government has the capacity to positively intervene in the hardships and inadequacies experienced by the people in Mathare and across the country. So far, we have only heard of initiatives which have never been implemented.

Worse, it remains difficult to stage mobilisations which express discontentment over the government’s apparent inaction on the current food crisis. The sight of police lorries patrolling Mathare and other areas is usually enough to silence dissent even among members of civil society.

One way of ensuring food security is to invest in irrigation systems in public lands, including the Yatta region, where most of the commercial produce come from. If people can have access to these public lands and if these lands have access to water, people would be poised to plant and harvest their own food.

It is so sad to learn that we are getting some relief goods from Egypt, a country whose food production is mainly irrigated by the Nile River that has its origins in Lake Victoria in Western Kenya.

But the dream of many women in Mathare still begins with having their own lands and households — spaces to grow their own food and grow on their own.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.