Visualising Power, Documenting Resistance

Visualising Power, Documenting Resistance

Persistently harrassed by the government, Iranian film maker Mahboubeh Abbasgolizadeh has found her mode of resistance in her craft. Her films have not only dealt with women who are oppressed by a fundamentalist regime. Behind the otherwise simple plots are real relations of power, that tells us much about Iran.

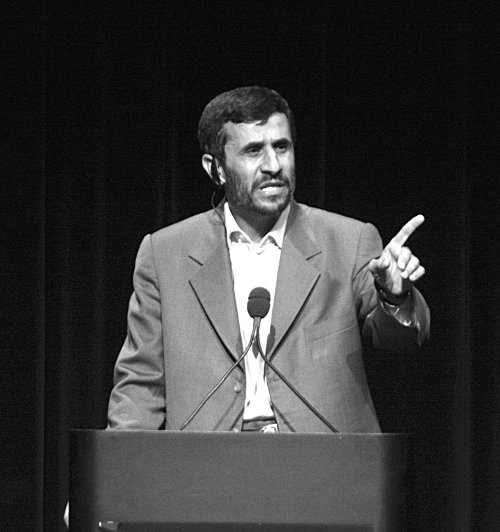

Armed only with the Camera. Iranian feminist and filmmaker Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh has documented the lives of women enmeshed in the country’s political issues such as the legitimacy of Almadinejad’s regime, women and the family law and stoning on grounds of adultery. She was once more arrested last 20 December 2009 while on her way to the funeral of Ayatollah Montazeri. Although she was immediately released, her companions were not as lucky.

Photo by Arash Ashoorinia

How would you assess the way media projected the “people power movement” around the time when the elections was severely contested?

In Iran, we do not have private television or radio. All media are run by the fundamentalist part of the government. So they control the news. They deliver their own messages and change public opinion. They own the policy.

They also control digital spaces. Nokia and Siemens sent Iran some eavesdropping instruments, so the government can control even text messages. The Ministry of Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) also controls all internet service providers and satellites. It can check the mailboxes of people. Most international websites like Youtube and Facebook are also filtered.

Though the government has developed strategies to control information and media, civil society creates new strategies everyday.

This is the reason why our website Meydaan has changed its domain several times. In fact, most Iranian women’s websites have been filtered so many times that they also have to change their administrators’ keys.

But people, especially the young, know ICTs very well. They could get around the filtering systems even those of Youtube and Facebook. Though the government has developed strategies to control information and media, civil society creates new strategies everyday.

Now Playing. The rallies, including the chanting on the rooftops “Death to the Dictator” were captured on amateur videos that were sent to platforms like Youtube, Facebook, Twitter and others. Perhaps the most stirring image was the death of a young woman, Neda Agha Soltani, who was shot in the chest as she went to check the protest actions. Violent crackdowns followed the protests. Officials said that 36 died but Mousavi’s camp asserted that the deaths were double that number.

Screenshot of Neda’s death from Youtube by an anonymous person, posted on Wikimedia Commons.

Then some parties also own media outfits outside Iran and broadcast information in places like Dubai, London and Washington. Because of censorship, people become more interested to hear the news from the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) or VOA (Voice of America), regardless that the latter follow Western policies. So the lesson here is that had Iran opened the media to the private sector, this would be better for democracy and people would not have to follow British or American news.

How have the people used media to deliver their own messages?

After Almadinejad’s first term, most civil society, especially women’s organisations were shut down. The regime would not allow women participate in the public sphere. So we changed our strategy, shifting from real spaces to digital spaces. We used new technologies such as video for documentation. This way, we managed to continue our advocacies.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad assumed the presidency in 2005, with the support of the country’s conservatives. Known for his fiery rhetoric against the West, particularly the United States, Ahmadinejad staunchly defended the country’s nuclear programmes despite warnings from the United Nations Security Council. He has consistently attempted to “re-Islamicise” women by introducing legislations on polygamy and divorce, among others. Ahmadinejad took away the wives’ right to oppose their husbands’ desire to marry other women. He also introduced a law that would allow husbands to divorce their wives without informing the latter and without providing alimony.

Sources: British Broadcasting Corporation (nd). “Profile: Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.” URL: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/ middle_east/4107270.stm and Taheri, Amir (8 September 2008).

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

I think this was the first time in the history of media where unprofessional and low quality video became a source of news. And these are actually people’s views, different from journalists’ views. This is indeed an interesting phenomenon that has yet to be thoroughly studied.

How accessible are these new technologies and who are capable of using these technologies?

Ordinary videos can be made through mobile phones. In just 10 minutes, you can upload this to Youtube, passing through the filter. And in a short while, the world can see your video. You can also send your link to mailing lists.

When the video that documented the death of Neda was uploaded, it was spread in just one or two hours and reached CNN, BBC, Al Jazeera and others. Presently we have good documentaries about the green movement but all the footage came from Youtube.

Not Another Stoning Story. In 2008, Mahboubeh produced a seven-minute documentary on stoning, a penalty that is imposed for adultery. In Waiting to be Stoned, Mahboubeh narrates the case of Mokarameh, who had been in prison for 10 years. Her partner, Jaafar was also arrested and stoned to death. Both have a son, who was born in prison. Mokarameh was previously married but her husband abandoned her and her two children. The film also featured Shadi Sadr, a feminist lawyer who eventually took up the case of Mokarameh. Waiting to be Stoned and the other films of Mahboubeh can be seen on Youtube.

What inspires you in making films on women using simple tools?

We are activists, first and foremost. We need our own agencies. When you have campaigns like stop stoning or end polygamy, you do a lot of things but somehow you wait for somebody to come and document these things. And this is like a disability. Sometimes, we have lots of meetings, where we invite camerawomen and directors. But sometimes, they fail to come. Or if they ever came, they missed the message.

But when you make your own video, you have agency, you have the ability. So through the camera, you can help women empower themselves. You can send your message, your perspective to a wider audience.

My main motivation in making documentaries is to change the situation of Iranian women and strengthen feminist agency in Iran.

There is really a difference between professional and feminist videography. The latter is part of our solidarity with the women’s movement’s demands.

Right now we are in a digital world and we need to use different types of media.

What are your favorite topics whenever you make documentary films?

The topics of my films are not mine. They are those of the women’s movement. We have campaigns to end polygamy, change the family law, stop the stoning of women and many others. I am committed to send the messages of the women’s movement.

But the process in creating the message is totally individual. It is not just an ordinary reporting or a lecture. When you do documentaries, you think of a main idea, you select a subject from the women’s movement’s activities. So in the Stop Stoning campaign, I focused on Mokarameh, the character who is waiting to be stoned.

But there is really a difference between professional and feminist videography. The latter is part of our solidarity with the women’s movement’s demands. So when I showed my films to my friends, they were excited because my films reflected their own dreams.

How would you describe the situation of Iranian feminists, especially with the kidnapping of Shadi Sadr and others?

This is a turning point in the women’s movement in Iran. For 100 years since the institutionalisation of the revolution, our activities have concentrated on legal reforms such as divorce and stoning. This time, we are challenged on how to reconcile women’s movement’s demands and the green movement’s demands.

I cannot say, “you go with the green movement so you can democratise society while I go to feminise society.” So how do we negotiate between green movement’s demands and women’s movement’s demands? We say that through women’s rights, we can democratise society. This, while we engage democratisation rights. But this is just one challenge.

Green Movement

The other challenge lies in the pressure from fundamentalist government and the military system. They want to control the green movement, civil society and individuals who have the capacity to organise people. They arrest leaders from the student’s movement to the feminist movement to the reformist movement. The second challenge is what poses risks and greater difficulty for we cannot go out collectively.

So how do we balance our roles in the green movement and the women’s movement and deal with the government’s pressures?

A few months ago, two sides worked against violence against prisoners, demonstrators and victims. We started to hold collective activities such as ceremonies, demonstrations in front of prisons and with the prisoners’ families. But we, women were not satisfied with demonstrations.

Being a feminist is not a profession. I cannot change my life as a feminist. It just came from my heart, my personality. It is my identity.

So we went and asked the guards to be quiet. We told them, “The prisoners are not your enemies. They are just like you. Do not do anything violent.”

As a feminist activist, is there anything that you would have done differently with hindsight?

I started my feminism through a nongovernmental organisation (NGO). If I had the chance to turn back the time, I would not go back to the NGO. I don’t believe we can only have a real movement through the “NGOisation” of the women’s movement. In Iranian society, many NGOs are created by the government. But NGOs should be created by ourselves.

At that time, we did not have enough structure and framework, so it was a big fault. If you don’t have any framework, principle or discourse, if you go to work for an NGO, you cannot really say that you are working for women’s issues. You are just an agent of development programmes.

You are harassed all the time. Do you have any regrets about being involved in this very vibrant but precarious movement?

Being a feminist is not a profession. You do not actually have a choice. Being a feminist is me. There is very famous sentence, “The personal is political.” So all my activity is me. I cannot change my life as a feminist. It just came from my heart, my personality. It is my identity.

I don’t believe also that people have multiple identities. Feminism is the main part of one’s identity and one just builds on this identity.

I don’t have a choice in being a feminist so I am not sorry about anything. But feminism is not static but it is dynamic. So everyday is a different feminism, a different feminist.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.