“New Politics” in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Renewed Threat to Women

The past few decades has seen the Latin American and Caribbean continent undergo profound social, political and economic changes that have included some sweeping contradictions, subjecting social actors in the region to a continuing and reiterated acculturation processes. Evidence of these disruptions can be found in the fact that the region has the most unequal income distribution on the planet.

Globalisation with the introduction of open market systems has only exacerbated this inequality. Growth rates in the region over the past two decades have talkingpoints been insufficient to extend opportunities for the well-being of the entire population. Wealth has also been concentrated among the already affluent. When growth is slow, less permanent jobs are created, limiting the mechanism of employment as a pathway to social integration and poverty eradication. Indeed, it is notable that women are overrepresented in the informal labour market.

Photo by Iose from Wikimedia Commons

When economies are not dynamic, social mobility and government spending tend to be limited, which in turn, hinders the reach of social policies that seek to provide all members of society with full rights.1

In such scenario, a variety of actors is playing a central role in the region’s conflicting dynamics. On the one hand there is the weakening of the state, which more and more has limited its regulatory role, abandoning almost completely its mandate to guarantee basic rights and services to all citizens.

In parallel—or perhaps as a consequence of weak states—the region has seen the rise of fundamentalist forces that in one way or another have caused setbacks in the recognition of individual human rights. Thus, despite major advancement in some areas such as educational programmes and laws that protect women’s human rights, different forms of discrimination still exist.

Across the region, we have witnessed with concern and impotence the emergence of different violations of women’s basic human rights that are not sufficiently noticed nor acknowledged, much less addressed.

Eight pink crosses were erected at the site where eight bodies of women were found in Cuidad Juarez. Photo by Iose from Wikimedia Commons.

One of the more industrialised Mexican towns near the border with the United States, Ciudad Juarez has been the site of more than 500 murder cases that have targeted women and girls since 1993. In many cases, the victims bore the signs of torture particularly rape and mutilation. Many victims that were identified were also factory workers. Nobody has ever been prosecuted. It is for this reason that the town has also been called the city of dead.

Ciudad Juarez hosts a number of factories and an ever increasing number of migrant workers from other parts of the country. Most factories have historically preferred young women as workers because of they tend to work harder and complain less. Not surprisingly, these factories have also discriminated against women of child bearing age and pregnant women, so as to evade the provision of maternity benefits.

With the unabated killings of young women, several formations emerged. However, leaders and their relatives have eventually been harassed and even tortured and murdered by unidentified groups. In just two days, Flor Alicia Gomez Lopez, 23 and Jesus Alfredo Portillo Santos, 27 were murdered on 28 and 29 November 2009. The niece of Alma Gomez Cabellero, a member of Justicia para Nuestras Hijas (Justice for our Daughters), Lopez was also raped. Meanwhile, Santos was the son-in-law of Marisela Ortiz, founder of Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa (Our Daughters Returning Home).

In a statement of Nobel Peace winners, they asserted, “Mexico’s systemic failure to investigate these murders violates numerous international human rights obligations in the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women ‘Convention of Belem do Para’ and the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, both of which have been signed by the Mexican government.”

In December 2009, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the Mexican government culpable in the murders and ordered it to pay the families US$800,000.

Sources: Harman, Greg (6 May 2009). “Lawsuit blames Mexican government for Juarez femicides.”; Frontera del Sur (15 December 2009). “International Court Holds Mexico Accountable for Femicides.”; and Nobel Women’s Initiative (8 December 2009). “Nobel Peace Laureates Condemn Murders in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.”

A case in point is the alarming number of femicides in the region, especially the deplorable situation in the Mexican states of Ciudad Juárez, Sinaloa, Jalisco and even Mexico City, and more recently in Guatemala, where more than 3,500 women were murdered between 2004 and 2009. Of these 700 annual deaths from machista violence, estimates show that close to 90 per cent have gone completely unpunished.2

The situation is similar for Colombian women who experience armed conflict. These women are victims not only of the more traditional forms of physical, psychological and sexual violence. They also experience threats to their lives and bodily integrity. Added to this situation are the violations and crimes perpetrated by the state itself which have been sufficiently documented in recent years by international human rights organisations.

Despite the demands of women and even the medical community, Nicaragua still bans the performance of abortion even in cases of health risk and rape. Among the United Nations agencies that criticised the country’s blanket abortion include the Committee against Torture, the Human Rights Committee, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Although Nicaragua leader Daniel Ortega is known to be notorious in other respects such as press freedom and electoral process, the hands of the Catholic church is seen in the total ban on abortion. Ortega used to support women’s sexual and reproductive health not until he was elected with the help of the church.

Source: Countries at the Crossroads Governance Blog (16 June 2009). ”Nicaragua’s Ortega Brings No Revolution to Women’s Rights.”

Within this scenario, Latin American and Caribbean women find themselves caught between the different political currents that promote their own projects in the region. Indeed, all of these movements have used advances in the recognition of women’s human rights as a bargaining chip to gain ground in their respective political alliances.

However we observe greater setbacks in countries that call themselves leftist or socialist.

The case of Nicaragua is emblematic in this regard. Recently, the Sandinista government coalition led by Daniel Ortega in partnership with liberal sectors and the catholic church, pushed through a law to repeal women’s legal right to therapeutic abortion, that had been in place for more than 30 years. Opposition to this move by feminists and women’s groups was effectively blocked by state agents by means of political persecution, criminal charges and threats against lives and reputations. Many of these women had actually supported the Sandinista revolution.

The analyses of social and political realities of the region reveal a high degree of fragmentation of the social fabric, coupled with the appearance of new actors with specific and isolated projects that respond to segmented demands rather than the general interests.

Unfortunately, the situation is no better in countries that are recognised for their progressive position and modernist social and economic stances. A case in point is Chile, which has a woman and socialist as president of the republic. Although the president established a directive to provide emergency contraception pills free of charge through the country’s public health system, her order could not be followed as it was ruled unconstitutional by the the country’s judiciary.

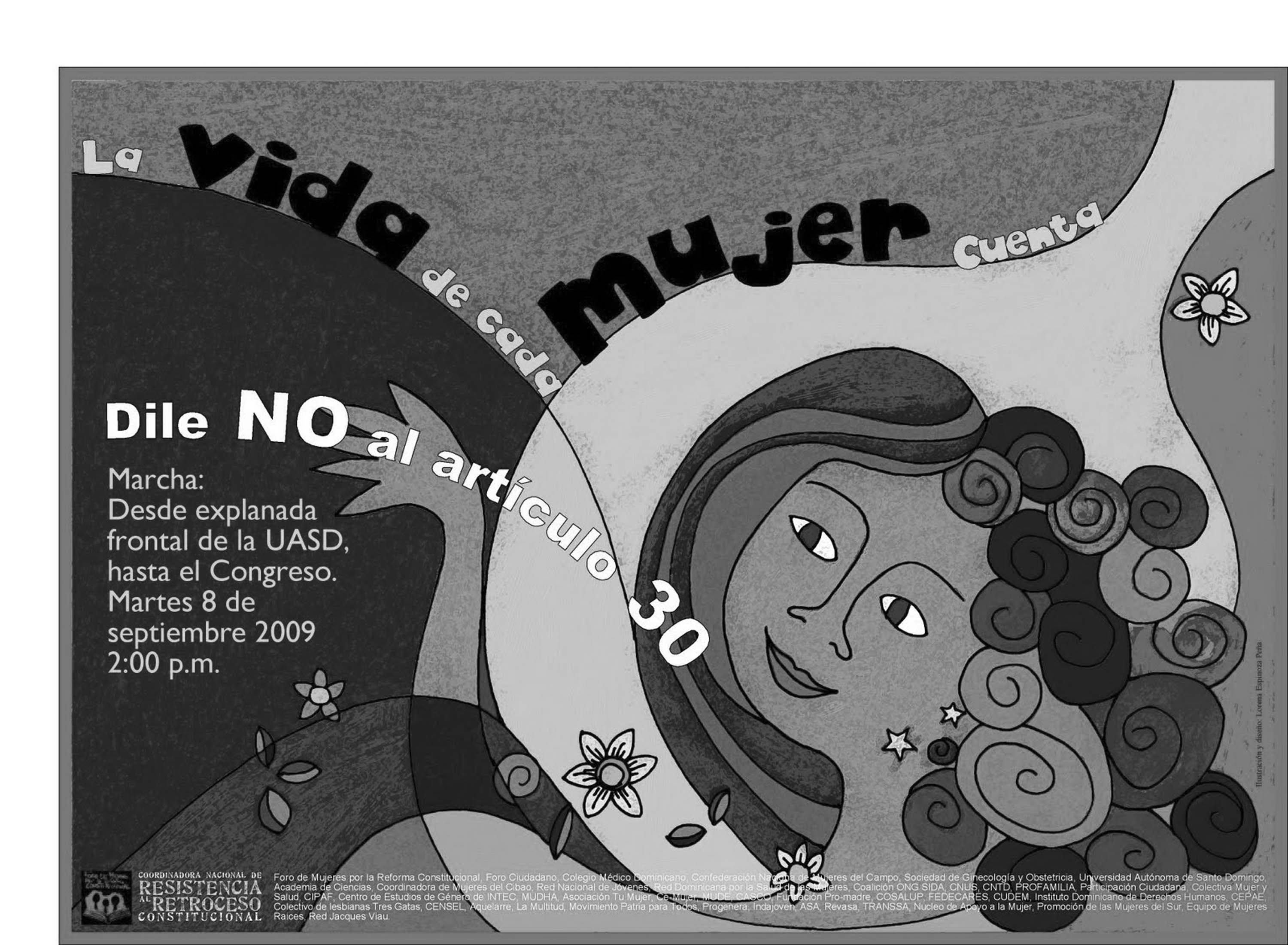

Source: Elliott-Buettner, Elliot (7 September 2009) “SRHR Situation Report: Abortion in the Dominican Republic.”

The situation is even more serious in U r u g u a y , where the proposed Sexual a n d Reproductive Health Defense Law was vetoed by the president. The latter refused to accept the provision to d e c r i m i n a l i s e abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy since this goes against his Christian faith. Brazil is likewise moving towards securing greater guarantees and privileges for the Catholic church.

The Caribbean subregion has not been immune to the wave of setbacks in women’s all political groups. The recent inclusion of Article 30 in the Constitution of the Dominican Republic, protecting life from conception to death from natural causes, has closed off legal avenues to recognise women’s freedom of choice in sexual and reproductive matters.

These regional and global socio-political realities and economic development models have not only failed to alleviate poverty. They have had an especially strong impact on women, aggravating already precarious lives that are mired in poverty and marginalisation. In such circumstances, gender violence becomes more severe, especially in times of economic, political and social crises: Hard times force more women and girls into high risk situations in the sex trade, child prostitution, precarious employment and virtual economic slavery, migration for economic and political motives and sexual exploitation, among other dangers.

The regional outlook remains bleak despite the socalled “alternative” politics posed by Brazil, Venezuela and other socialist governments.We witness the return of external interventions that will undoubtedly heighten existing conflicts and deepen inequalities.

Despite the efforts of some governments, international agencies and civil society organisations to prevent and eradicate sexist, discriminatory and stereotyped behaviors that stigmatise different segments of the population, such behavior persists, expressed in different forms and nuances. In our globalised world, problems related to women’s health and integrity have become more than national concerns, as governments seem unable to adequately implement policies and programmes to eradicate, prevent, punish and respond to violations of women’s human rights.

Photo from Wkimedia Commons

As the evidence shows, advances in women’s human rights are neither final nor constitute a permanent guarantee. Today, women’s struggles in Latin America and the Caribbean are more important than ever. They seek not only to gain new grounds in the fight for full recognition of their human rights, but also to slow down the onslaught of regressive and fundamentalist forces that are present, active and decisive in Latin Amerinca and the Caribbean.

Sandra Castañeda Martínez is a consultant of Isis Internacional in Santiago, Chile. She is also involved in the Lation American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network (LACHWIN)

Endnotes:

1 ECLAC/ SEGIB/ AECI (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean / Secretaría General Iberoamericana/ Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional) (2007) “Social Cohesion. Inclusion and a Sense of Belonging in Latin America and the Caribbean” L/CG.2335, Santiago, Chile.

2 Isis Internacional. www.isis.cl

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.