Simultaneous and Serial Struggles: Women and Fundamentalisms in South Asia

Simultaneous and Serial Struggles: Women and Fundamentalisms in South Asia

Women across the world have always spoken out against militarism and all other forms of violence as unacceptable. The States’ strategy for resolving differences have often resulted in militarism and wars in South Asia and beyond. But just as worrying as the brewing and ongoing conflicts is the fast growing fundamentalisms in the global order.

The growing insecurity in South Asia can only be attributed to the destruction of social and secular fabrics — exacerbated by increasing the re-emergence of fundamentalisms and rapid globalisation. Such insecurity has further cast a shadow on the possibilities of peace and development for women. In fact, women have been used in bolstering the religious identities of different sects, as exemplified in various ethnic cleansing programmes.

Illustration by Nicholson Cartoons, http://www.nicholsoncartoons.com.au

When a singular homogenising model is imposed, diversity is quashed, dissent is silenced and ultimately identities become invisible, if not lost.

Feminist scholars have always found a strong link between militarism, on the one hand and the aggressive politics of masculinity, fundamentalisms, global capitalism, politicised religious groups and ethnic nationalisms, on the other hand. For instance, the right wing groups with religious fronts such as Hindutva have been undermining the secular forces in India, as is the Jihad in Pakistan and HuJi in Bangladesh — all embedded within militaristic and fundamentalist ideologies. These groups have propagated prejudices in communities, rendering the minorities, women and other marginalised groups vulnerable.

Massing Military

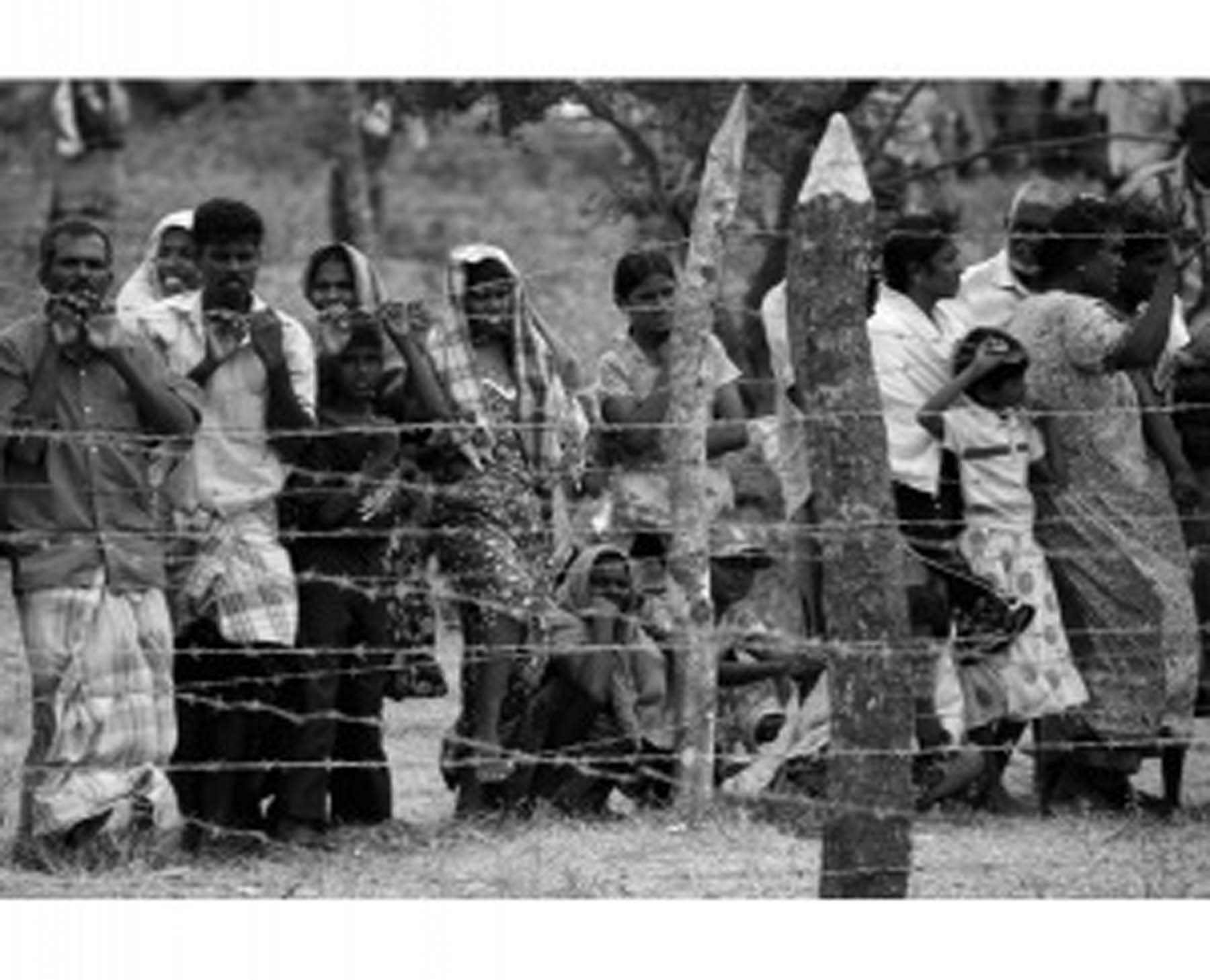

Sources:Amnesty International (18 May 2009). “Sri Lanka: Urgent Need for Human Rights Protection.” ; Hosken, Andrew. (7 May 2009). “Despair among Sri Lanka’s refugees.”; Human Rights Watch (May 2009). “Sri Lanka: Trapped and Under Fire.”; International Committee of the Red Cross (14 May 2009). “Sri Lanka: humanitarian assistance can no longer reach civilians.” ; and Zemke, Lydia (14 May 2009). “Sri Lanka: Intl Condemnation Mounts, Along With Body Count.”.

Photo from South Asia Speaks.

And yet there are no signs that the subcontinent is about to pause and ponder over the physical toll of conflict and wars. On the contrary, the whole of South Asia is envisaged to significantly increase its budget allocation for defence. Every South Asian country justifies the increase in military expenditure on the pretext of protecting the country’s security from external threats and more so from internal conflicts over ethnicity and natural resources.

Pakistan’s military allocation is instructive. The country’s defence budget has increased four fold while half of its population has been absorbed by its military. Hence, it is often said: “While every country has an army, the Pakistan army has the country.” The heavy spending on militarism, particularly the purchase of arms has severely cut the budget for social sectors like health and education, with women and children absorbing many of the negative consequences.

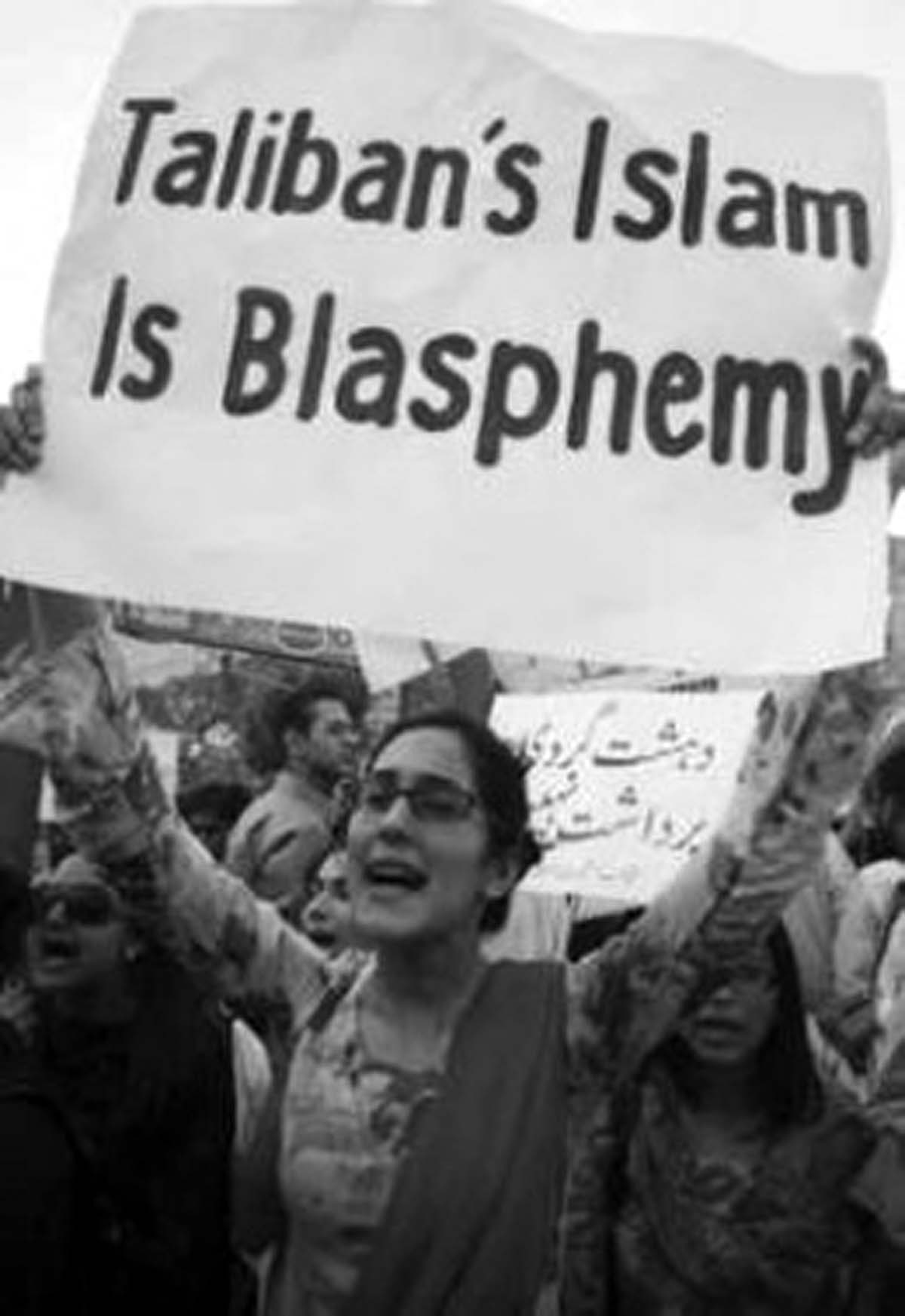

Photo from the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan

Feminist scholars throughout the world have likewise extensively examined the relationships between patriarchy, masculinity and militarism, on the one hand and violence against women and children, on the other hand in the context of ethnic cleansing and in the very oppression that stems from interests within particular caste, class, race and gender.

This is very much evident from the persistent ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka, where. Tamil women and children were raped and killed and their bodies mutilated. Up to now, there is a dearth of data on the number of women and children who were killed in this worst holocaust by the Sri Lankan army.

Under the Robe of Religion

Meanwhile, the aspirations of women in Afghanistan and Pakistan are being shattered with the strict religious laws imposed by the Taliban. Women and girls are not allowed to visit a doctor nor a hospital. They are also prohibited to buy basic essentials. They cannot study nor work. Should they dare to come out in public, they face the risk of being stoned and flogged in the presence of their fathers, sons, husbands, brothers and other family members. The fundamentalist diktats of the Taliban have indeed obfuscated Sharia law into one that is extremely limiting and even inhumane. Moreover, it has reduced women and children to deplorable poverty where they survive with mere crumbs or die of starvation.

Photo from the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan.

Tamil women and children were raped and killed and their bodies mutilated. Up to now, there is a dearth of data on the number of women and children who were killed in this worst holocaust by the Sri Lankan army.

The growth of religious fundamentalism in India likewise highlights the glorification of masculinity through militarism and the belittling of femininity through peace. In fact, such glorification, including its bloody implications has been sanctioned by the country’s biggest political parties.

The Sanga Parivar collective has found allies in groups such as Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Bhajrang Dal, Rashtria Swamsevak Sang (RSS) and Shiv Sena, which have all instigated hate campaigns throughout India. It even has strong links with India’s oldest party, the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP), whose ruling regime prosecuted relentless attacks against Christians and other minorities. These attacks included the murder of priests, the rape of nuns and the destruction of Christian institutions, schools, churches, colleges, and cemeteries. Between 1992 to 1993, thousands of Christians were forced to convert to Hinduism.

The stunning brutality of the Gujarat carnage, where more than 2,000 people died captivated both independent and mainstream media that in almost no time, the carnage was replicated albeit targetting Muslim communities. Muslim women were raped and killed with their bodies mutilated and burned. Bodies of women were not merely used as weapons of war but were seen as the locus of communities that must be destroyed.

The Tyranny of Trade

Photo from Committee for the Abolition of Third World Debt.

Market-driven globalisation has similarly coopted the global order which continues to destroy rather than revive communities or encourage alternative spaces. As governments are becoming more partial towards neoliberal frameworks, they increasingly distance themselves from welfare measures, facilitating the conversion of education and health services into commodities.

The progress of market fundamentalism rests in all spaces of social life. Seen in this light, neoliberalism’s endurance becomes even more telling. This, as a market-driven logic puts market interests above human necessities and desires.

Fundamentalisms are therefore the exaggerated and absolute face of the patriarchy. Its dominance that is based on an irrational form of discipline suggests a case of terror that pre-empts punishment.

Hostaged Meanings and Spaces

But communities were not the only ones destroyed but the very spaces where collective traumas could have been processed. A culture of submission was promoted by the censorship directed at debates and discussions on differences of opinions.

Such censorship indeed shakes the very core of citizenship especially among minorities for whom increasing insecurity typically means decreasing access to their abode, lands and the natural resources around them. For attacks against minorities are done through the destruction and confiscation of their land, where their identities are deeply anchored and where their basic survival depends. The recent attacks against the Christians in Kandamal in Orissa have resulted in the eviction of Christians from the forested areas where they lived much of their lives. These Christians and other minorities are further subjected to notorious profiling and surveillance.

Censorship indeed shakes the very core of citizenship especially among minorities for whom increasing insecurity typically means decreasing access to their abode, lands and the natural resources around them.

In 2002, the BJP government passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) under the pretext of insulating the country from terrorism but this was abused by the BJP who implemented the bill targeting political opponents, human rights defenders, minorities and even tribal children in Jharkhand and Chatisghard in the name of the anti-Maoism.

But mass violence is not exclusive to countries with overarching security laws. In some cases, silence is enough to sanction exclusion and violence. The Sri Lankan government, for instance, kept its eyes shut amid religious conflicts which resulted in murder and injuries among minorities, women and children. This inaction has only fortified the strength of fundamentalist groups that continuously deem illegitimate a government initiative, however potentially empowering it might be, as in the case of Sri Lanka’s 2008 National Women’s Development Policy.

Sources: AFP (25 October 2007).”Gujarat state head ‘supported Muslim massacre.’”, Rhys (24 November 2009); “World Agenda: BJP in the frame for Babri mosque massacre.” ; Rajagopa, Arvind l (20 March 2003). “Gujarat’s ‘successful experiment.’”

Photo from Anti-Caste.org

Recent incidents such as the 26/11 Mumbai Terror, the Sri Lankan war against the Tamil Tigers, the internal terror attacks in Pakistan and Afghanistan are further narrowing the definitions of nationalism, national interest and national security.

Still a Struggle

Yet feminists in the sub-continent are not about to give up. Instead, they persistently challenge notions of nationalism, national interest and national security. For them, a genuine understanding of security must be less State-centric but more society-centric. They further assert that there can be no security without social, economic and political liberty and justice.

For years, women’s agenda are always the first to be sacrificed especially by reactionary forces that are tied up with religious fundamentalist institutions. Such effacement cuts across class, race and nations. Divide and rule policies further subject women to the margins. Although women may not share the standing of minorities, their bodies are at once the object and foundation of unfair social stratification. Nonetheless, the long-standing and variegated experience of exclusion has informed and sharpened women’s perspective on the linkages among religious fundamentalisms, militarism and neoliberal globalisation.

Photos from Citizen Trust

Women’s daily lives can be likened to their occupying “paradoxical spaces.” One must continue to understand the ways by which militarism, religious fundamentalisms and economic globalisation converge and thrive.

What is becoming more difficult to reconcile towards a universal struggle is the series of differences in our experiences of sexuality and reproduction. While this makes the struggle for universality in women’s human rights more difficult, it also makes the struggle more critical and necessary.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.