More Under the Veil: Women and Muslim Fundamentalism in MENA

It is important to begin any discussion related to religious fundamentalism with an exploration of what is meant by the term “fundamentalism.” The word “fundamentalism” was originally coined in reference to a movement within the Protestant community of the United States in the early part of the 20th century. In the broadest sense, fundamentalism can be understood as “a selective retrieval and imposition of...[religious] law and sacred texts as the basis for a modern socio-political order” (Hardacre 1994:130).

Source: Amnesty International (25 November 2009). “Yemeni women face violence and discrimination.”

In photo is the city of Sanaa from Wikimedia Commons

But religious fundamentalism is not a monolithic entity. Around the world, there is a wide range of fundamentalisms and fundamentalist movements that display a number of similarities – most notably their interpretation of the family, gender roles and interpersonal relations – but in no way share identical plans. Generally speaking, the ideologies of fundamentalisms have translated into movements that show little respect for the principles of human rights and have little tolerance for people of other faiths. They are often anti-women (Rouhana, 2005).

The issue of women – their status, rights, roles and responsibilities, both within the family and the community – is one of the main focuses of fundamentalist discourses.

For quite some time, women from Middle East and North Africa have been the subject of concern. Yet there is much more to be explored about their methods of resistance.

Women are seen as the bearers of cultural authenticity (Kandiyoti,1993) and their complicity within the religious framework is necessary to its survival. As Gita Sahgal and Nira Yuval-Davis in Refusing Holy Orders pointed out, “(t)o conform to the strict confines of womanhood within the fundamentalist religious code is a precondition for maintaining and reproducing the fundamentalist version of society.”

For quite some time, women from the Middle East and North Africa have been the subject of concern and the rallying point of feminist advocacies and campaigns whose language has been coopted by right-wing fundamentalist regimes in the West on many occasions. Yet there is much to be teased out the deprivation and violence these women experience and much more to be explored about their methods of resistance.

Muslim Fundamentalism in MENA

The rise of Muslim fundamentalisms since the 1970s should be viewed through the trends towards modernisation and perceived threats of neocolonialism. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, which is characterised by the rapid spread of globalisation, newly-formed nation-states attempted to hastily develop and compete in a globalised world.

In many regions, this often translated into the adoption of neoliberal economic policies and the further inclusion of women in the public sphere. Women had already begun to take a more active public role through anti-colonial and independence movements.

New nation states indeed emerged in the 1950s, many of them formally severing their links to various empires. There are obvious exceptions to this trend though such as Palestine as it is still in the throes of its struggle for independence and Iran which was never a formal colony.

This resurgence could be partly viewed as a backlash against the failure of secularised states to effectively develop and maintain “cultural” integrity – the issue of women’s sudden inclusion in public spaces being at the forefront. It was a period of great upheaval in reaction to social failures such as the non-provision of basic social services, rampant corruption and the growing gap between rich and poor, among others.

The dissatisfaction in the Muslim Middle East was further bolstered by the Arab states’ defeat by Israel in the 1967 war and the Western powers’ support for Israel, which was perceived as an outright attack on Islam and Arab “cultural authenticity” and an entrenchment of neocolonialism. All of these forces culminated in the coming of the 1979 Iranian Revolution which led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the first and only Islamic state in the region. But these factors have strengthened the resolve of Muslim fundamentalist movements across the entire region and have shaped the essential elements of Muslim fundamentalisms in the Middle East today.

Battle for the Hijab

Battle for the Hijab

In 2008, people gathered on the streets of Ankara to protest the decade long ban on the hijab or the head covering in public places and univeristies. While the government saw it as an aid to women who would like to participate more in public life, the ban has discouraged many women to study. The hijab, which covers the head up to the nape and the niqab, which covers the whole body save for a slit for the eyes, have been donned by Muslim women in the name of modesty. Islamic scholars remain torn though in interpreting the use of the hijab in moden times. But Open Democracy’s Fred Halliday put it nicely, “There is only one consistent, universalist and secular position on the wearing of religious headwear - for Muslims, Catholic nuns, or Orthodox Jewish haredim alike: to be against it, but to defend the right to wear it.”

Sources: Al Jazeera (6 June 2008). “Turkey’s AKP discusses hijab ruling.” ; Asser, Martin (5 October 2006). “Why Muslim women wear the veil.” and Halliday, Fred (16 December 2004). “Turkey and the hypocrisies of Europe”

Photos from Story og a Muslimah and the Lebanese Development Network

Muslim Fundamentalisms and Women

While women’s attire in Muslim contexts, the hijab – chador, burka, abiya – always receives ample attention from Western news sources, it is far from being the most important issue that women face in their confrontation with Muslim fundamentalisms.

In reality, it is the Shari’a–derived personal status laws governing women and the family where the influence of fundamentalisms is felt most acutely. Personal status laws govern marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance (Ziai,1997). In essence, personal status laws outline what women’s rights are and what they are allowed to do within the confines of the dominant interpretation of Islam in each specific country. Whether it be “Islamisation from above” or “Islamisation from below,” these are the most contentious laws around which both Islamists and women mobilise (Legrain,1994).

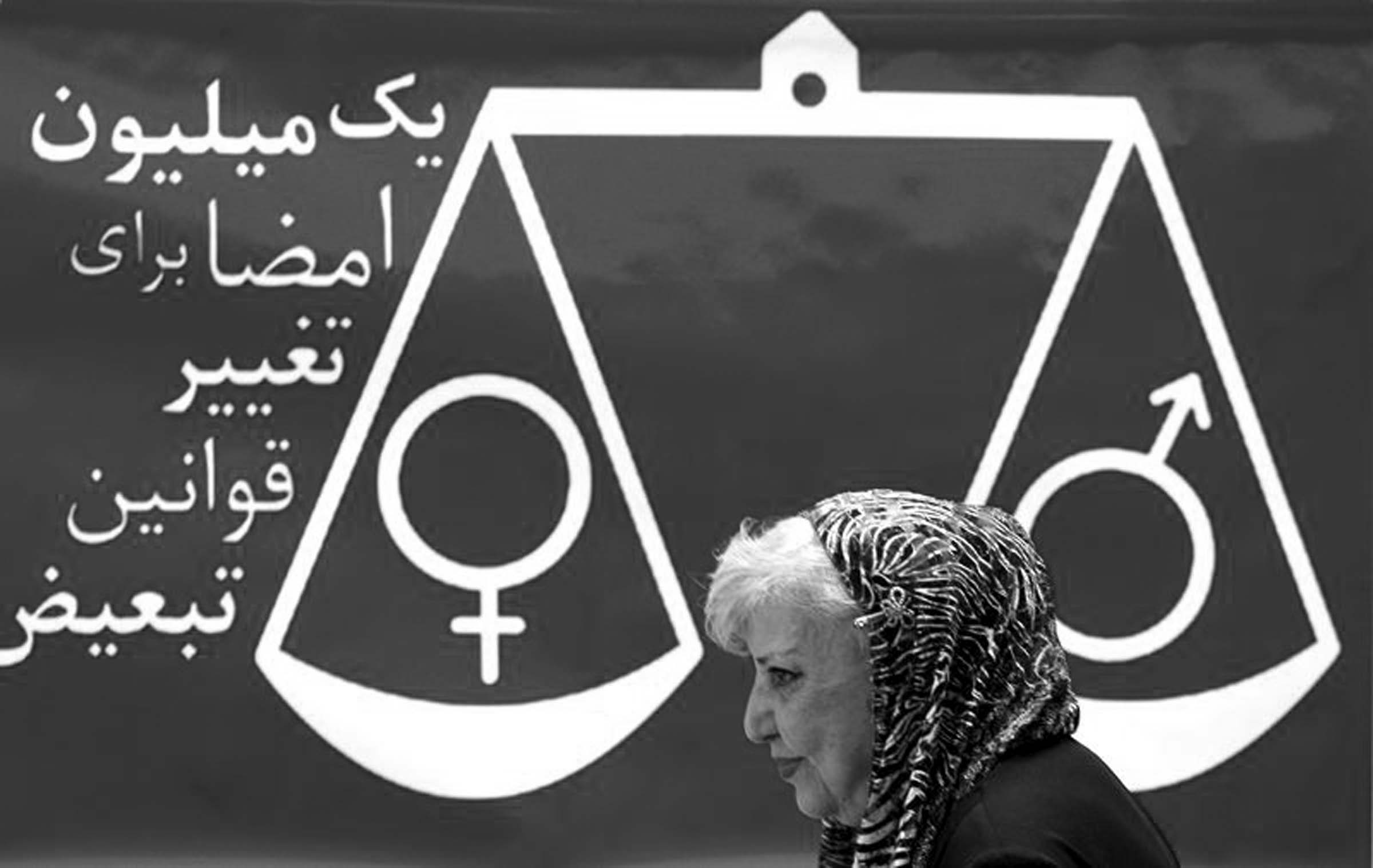

Although women in these contexts are sometimes represented as passive victims of fundamentalists’ projects, this is far from being the case. As previously noted, women were active participants in the struggle against colonialist and neocolonialist impositions and even up to the present with the continuing fight for Palestinian statehood. Moreover, women, including those observing the hijab, have actively mobilised around the perceived injustices enshrined in personal status laws. The One Million Signatures Campaign in Morocco in 1992, the One Million Signatures Campaign in Iran since 2006 and the protest movement in Iraq against the abolition of Iraq’s progressive personal status laws in 2003 are only a few examples of women-led mobilisations. These courageous women often expose themselves to reactionary criticism and risk being targeted as “puppets” in the neocolonial project.

Unlike bygone colonial times, when the enemy was defined quite clearly as the foreign occupier, during the current times of neo-colonialism and ongoing imperialism, “the other” can be found in the midst of the national fabric. And, the “other within” generally turns out to be the westernised middle classes, the nouveau riche, the religious and ethnic minorities, and . . . the human rights activist trying to uncover his or her government’s atrocious human rights record. But the “real favourites” when it comes to identifying “traitors” and “infiltrators”; are those “appalling women” who dare to defy tradition and struggle for their legal rights and greater equality. (Al-Ali, 2001:5)

The concepts of women’s rights as human rights and feminism are presented by these reactionary forces as a Western import in contradiction to “authentic” Muslim culture. These forces oppose proliferation of women’s rights movements and foreignfunded non-governmental organisations (NGOs), coupled with the new rhetoric propagated by the international community of women’s rights for democracy – as if democracy is inherent only to Western culture. But as Aili Mari Tripp in Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organizing, and Human Rights pointed out, “Regardless of the common perception in the West that ideas regarding the emancipation of women have spread from the West outward into other parts of the world. In fact, the influences have always been multidirectional, and that the current consensus is a product of parallel feminist movements globally that have learned from one another but have often had quite independent trajectories and sources of movement.”

Photo from Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty.

Furthermore, various feminisms have developed in the South. But even though there is ample evidence that feminism is by no means a purely Western conception, oftentimes just the use of the word feminism evokes accusations of Western cooption in confrontation with Muslim fundamentalisms.

Feminism is not a monolithic entity. In fact, feminism in Muslim contexts, has taken many forms. I will break down these feminisms into two broad categories, but it should be noted that these categorisations are in no way static and are continuously subject to debate. There are feminists, both non-religious and religious women, who choose to work within a secular framework in the articulation of their rights. These women demand that the laws governing the family not be based on Shari’a. They are, of course, under the most pressure from fundamentalisms.

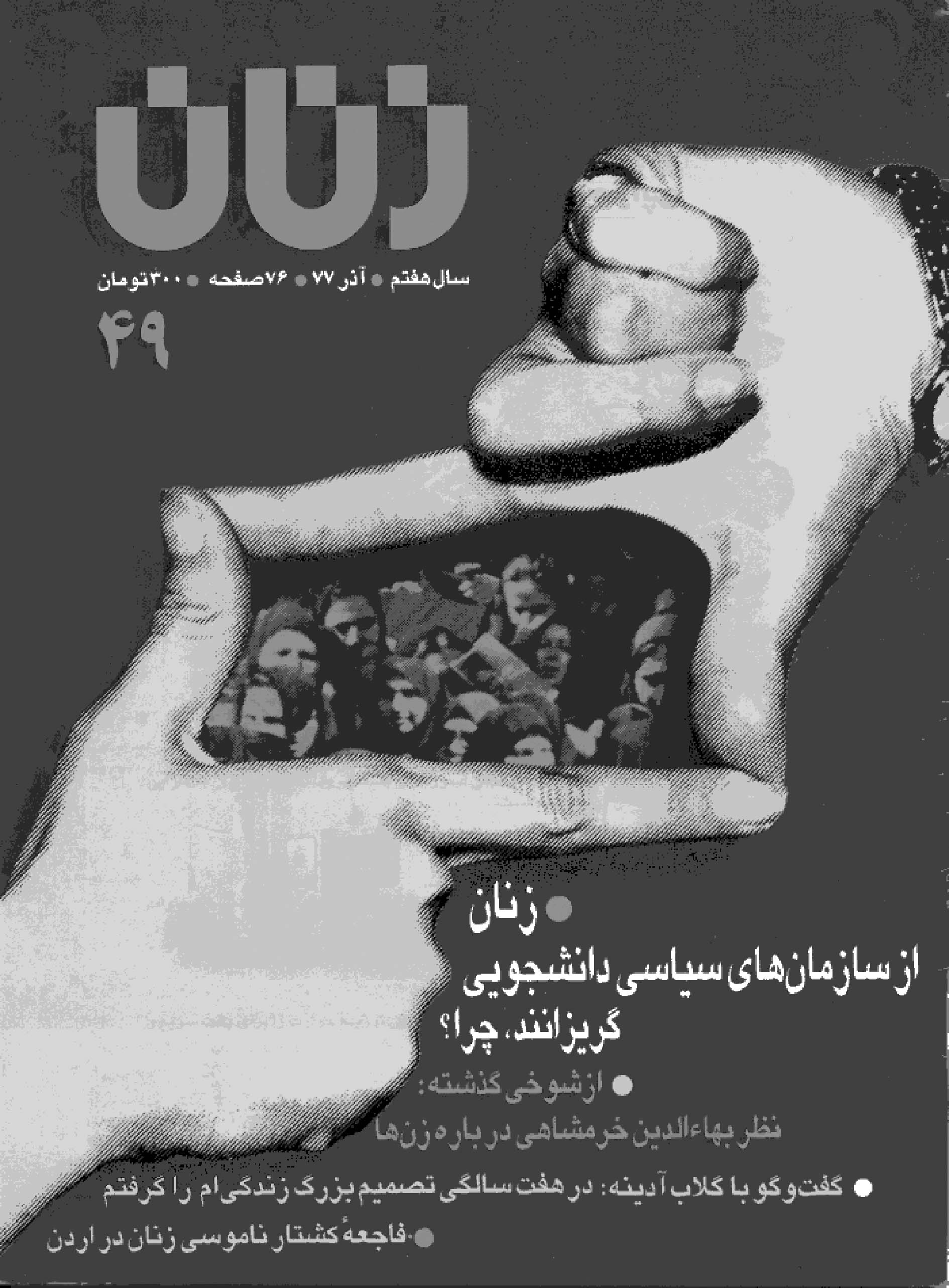

Recently the term Islamic feminism has also joined the debate on feminism in this region. Broadly speaking, Islamic feminism works to reconcile feminism with Islam in its cultural and political forms. This is why there is more than one conception of what Islamic feminism is. The first and most often articulated notion stresses a rereading of textual sources and a more egalitarian approach to Islam yet is also not hostile towards Western feminism. The women’s magazine Zanan, which began publication in Iran in 1992, can be seen as an example of this brand of feminism.

Zanan

After 16 years, Iran’s leading women’s magazine was ordered to be closed in early 2008. Meaning “women” in Persian, Zanan was accused of “offering a dark picture of the Islamic Republic through the pages of Zanan” and of “compromising the psyche and the mental health” of its readers by providing them with “morally questionable information.” Zanan featured articles on health, parenting, law, literature and other women’s issues.

Photo from the International Women’s Media Foundation.”

In photo is the city of Sanaa from Wikimedia Commons

More than 120 academics and humanMore than 120 academics and human rights activists like Noam Chomsky, Jurgen Habermas, Betty William and Shirin Ebadi protested the ban. Zanan was founded by one of Iran’s leading feminists, Shahla Sherkat.

Sources: Tehrani, Hamid (14 February 2008). “Iran: Protests over ban of women’s magazine.”; Learning Partnership (8 February 2008). “Zanan, Iran’s Leading Women’s Magazine, Shut Down by Government.” and New York Times (7 February 2008). “Shutting Down Zanan.”

As Ziba Mir-Hosseini described, Zanan advocated a brand of feminism that “takes its legitimacy from Islam, yet makes no apologies for drawing on Western feminist sources and collaborating with Iranian secular feminists to argue for women’s rights.” It reveals the lack of correlation between patriarchy and Islamic idealism but it does not conceal the gender inequalities in Islamic law. Moreover, it addresses such inequalities within the very context of Islam.

The second strand of Islamic feminism is an incredibly contentious one. It generally refers only to a small group of Iranian women who “seek the amelioration of the Islamied gender relations, mainly through lobbying for legal reforms within the framework of the Islamic Republic” (Mojab, 2001:130). These women, unlike women in the more “liberal” view of Islamic feminism, are quite hostile towards the use of the term feminism and Western feminism in general. One should also consider that these women are working to enhance their rights within the existing political structure of Iran. Its hostility towards the West might be a purely strategic choice. Hence there is an ongoing debate, both within and outside academia as to whether or not these women can actually be categorised as feminists.1

Even with women in parliament, women’s issues are still not a priority or even on the agenda. Rather, they represent the party in power and are only there to toe the line.

Although women in Muslim fundamentalist-influenced societies have been incredibly active and have participated in the gradual growth of civil societies, this activism has not been incorporated into official political power structures to any significant extent. In recent times there have been more women representatives in political institutions, but this has not translated into the representation of women’s interests. For example, the new Iraqi Constitution requires that 25 per cent of the 444 parliamentary seats must be occupied by women. This was a hard fought battle by Iraqi women activists because as Sundus Abass stated, “the quota in Iraq was actually put in the Constitution by the influence of the Iraqi women, because even the Americans were against adopting the quota in the Constitution.”

Even with women in parliament, women’s issues are still not a priority or even on the agenda. Similarly Iran installed some women members in parliament but they are not interested in women’s issues. Rather, they represent the party in power and are only there to toe the line.

Sources: Brown, John (19 September 2005). “Semi-Slave Conditions for Foreign Workers in Dubai.”; Sharp, Heather (4 August 2005). “Dubai women storm world of work.” and Shreck, Adam and Jamal Halaby (7 January 2010). “Dubai downturn sends ripples throughout Arab world. ”

Photo by Josa Piroska from Wikimedia Commons.

Conclusion

I have painted a general picture here of the situation of Muslim fundamentalisms and women in the Middle East and North Africa. Even though similarities can be drawn between different movements all over the region, in truth, the details of each specific context have led to the emergence of a distinct type of Muslim fundamentalism. Thus it is difficult to compare the situation in Morocco with that in Iran. Although religious fundamentalisms have been on the rise for a long time in this region, women are in no way passive victims. Many women actively resist. They fight for their rights, engage in social justice projects, and espouse various forms of feminism. While there is no doubt that veiled, homebound and uneducated women exist, such image in no way encapsulates nor acknowledges the lives and struggles of women in Muslim contexts.

References

Abass, Sundus (2006). “Campaigning for Women’s Rights in Iraq Today”. In WLUML Occassional Paper 15: Iraq Women’s Rights Under Attack – Occupation, Constitution, and Fundamentalisms, edited by S. Masters and C. Simpson. London: Women Living Under Muslim Laws.

Al-Ali, Nadje (2001). “Reflections on Globalization”. Unpublished paper presented at annual Gulf Studies conference at the Institute of Arab & Islamic Studies. University of Exeter.

Al-Ali, Nadje and Nicola Pratt (2009). What Kind of Liberation?: Women and the Occupation of Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gerner, Deborah J. (2007). “Mobilizing Women for Nationalist Agendas: Palestinian Women, Civil Society, and the State-Building Process”. In From Patriarchy to Empowerment: Women’s Participation, Movements, and Rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. Edited by V. Moghadam. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Hardacre, Helen (1993). “The Impact of Fundamentalisms on Women, the Family, and Interpersonal Relations”. In Fundamentalisms and Society: Reclaiming the Sciences, the Family, and Education. Edited by M. Marty and R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kandiyoti, Deniz (1993). “Identity and Its Discontents”. In Colonial Discourses and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. Edited by P. Williams and L. Chrisman. Essex: Pearson Education Ltd.

Keddie, Nikki (2007). Women in the Middle East: Past and Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keddie, Nikki (1998). “The New Religious Politics: Where, When, and Why do ‘Fundamentalisms’ Appear?.” In Comparative Studies in Society and History 40 (4): 696-723.

Legrain, Jean-François (1994). “Palestinian Islamisms: Patriotism as a Condition of Their Expansion”. In Accounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements. Edited by M. Marty and R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mira-Hosseini, Ziba (2005). “Muslim Women, Religious Extremism and the Project of the Islamic State in Iran”. In Muslim Women and the Challenge of Islamic Extremism, edited by N. Othman. Kuala Lumpur: Sisters in Islam.

Mojab, Shahrzad (2001). “Theorizing the Politics of ‘Islamic Feminism.” In Feminist Review, The Realm of the Possible: Middle Eastern Women in Political and Social Spaces, 69: 124-146.

Ottaway, Marina (2005). “The Limits of Women’s Rights”. In Uncharted Journey: Promoting Democracy in the Middle East. Edited by T. Carothers and M. Ottaway. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Rouhana, Hoda (2005). “Women Living Under Muslim Laws (WLUML) Network’s Understanding of Religious Fundamentalisms and Its Responses”. In Muslim Women and the Challenge of Islamic Extremism. Edited by N. Othman. Kuala Lumpur: Sisters in Islam.

Saghal, Gita and Nira Yuval-Davis (1992). “Introduction: Fundamentalism, Multiculturalism, and Women in Britain”. In Refusing Holy Orders: Women and Fundamentalism in Britain. Edited by N. Yuval-Davis and G. Saghal. London: Virago Press.

Shahak, Israel and Norton Mezvinsky (2004). Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel (New Edition). London: Pluto Press.

Tripp, Aili Mari (2006). “The Evolution of Transnational Feminisms: Consensus, Conflict, and New Dynamics”. In Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organizing, and Human Rights. Edited by M. Ferree and A. Tripp. New York: New York University Press.

Ziai, Fati (1997). “Personal Status Codes and Women’s Rights in the Maghreb”. In Muslim Women and the Politics of Participation: Implementing the Beijing Platform (1st ed.). Edited by M. Afkhami and E. Friedl. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Footnotes

1 This is an incredibly rich debate. It ranges from people like Hamed Shahidian who believe “Islamic feminism” to be an oxymoron, to those who believe Maryam Behrouzi – Iranian Majles deputy – to be a feminist. Maryam Behrouzi, who would not claim to be a feminist herself, pushes for more female political representation within the Iranian Majles (from her own conservative Islamist party). She and many other practising Muslims do not believe in equality between the genders, because the individual is not counted as the unit of society. The unit of Muslim society is the traditional family which is constructed by marriage between one man and at least one woman). Therefore, men’s and women’s roles, responsibilities, and hence rights are not equal but complimentary – for the sake of the family.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.