Beijing Meets WTO

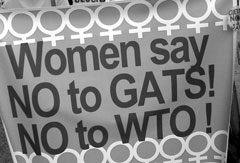

“National Consultative Forum on Beijing+10 Meets WTO+10” held on 09 December 2004 at Miriam College, Philippines was attended by 120 participants from 31 different trade and women’s networks and organisations in the country. Together with the International Gender and Trade Network (IGTN)-Asia, and with funding contribution from Oxfam Great Britain, the following national networks co-organised the forum to ensure a substantive exchange and dialogue on gender and trade issues: Fair Trade Alliance, Stop the New Round Coalition, Task Force Food Sovereignty, Freedom from Debt Coalition, Kilos Kabaro, Isis International-Manila, and International South Group Network. The IGTN is a network of feminist gender specialists that provides technical information on gender and trade issues to women’s groups, nongovernment organisations, social movements, and governments.

Built-in and new issues in the WTO were examined, assessing both the past ten-year experience and the potential implications on specific sectors and areas of the economy. Another forum objective was to allow the different women and trade networks to present their ongoing campaigns and determine any initial basis for future collaboration and intersecting action in terms of campaign strategies. Hence, the forum’s programme had three parts:

1. panel discussion on agriculture, clothing and textile, trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS) and the drug industry, and privatisation of public utility services;

2. panel discussion on the fisheries sector, cultural products, non-agricultural market access (NAMA), and General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS); and

3. plenary sharing on campaigns.

Highlights and Main Findings

A.Overarching BPFA commitments on macroeconomic and trade policies

In reviewing the implementation of the BPFA in relation to trade and macroeconomic policies in the Philippines, two BPFA commitments were identified as overarching. These commitments provided the main reference points for assessing what has been the role of trade and macroeconomic policies in either advancing or retarding the economic status of women, and in either alleviating or worsening women’s poverty. These commitments are the following:

BPFA Government Commitment 165(k): “Seek to ensure that national policies related to international and regional trade agreements do not have an adverse impact on women’s new and traditional economic activities”; and BPFA Government Commitment 58(b): “Analyse, from a gender perspective, policies and programmes–including those related to macroeconomic stability, structural adjustment, external debt problems, taxation, investments, employment, markets and all sectors of the economy–with respect to their impact on poverty, inequality and particularly on women; assess their impact of family well-being and conditions and adjust them, as appropriate, to promote more equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities, income and services.”

BPFA Government Commitment 165(k): “Seek to ensure that national policies related to international and regional trade agreements do not have an adverse impact on women’s new and traditional economic activities”; and BPFA Government Commitment 58(b): “Analyse, from a gender perspective, policies and programmes–including those related to macroeconomic stability, structural adjustment, external debt problems, taxation, investments, employment, markets and all sectors of the economy–with respect to their impact on poverty, inequality and particularly on women; assess their impact of family well-being and conditions and adjust them, as appropriate, to promote more equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities, income and services.”

The Philippines ratified the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade-Uruguay Round (GATT-UR) in late 1994 and was a signatory to the BPFA in 1995. Prior to these agreements, the country was already implementing, as early as the 1970s, a series of International Monetary Fund (IMF) structural adjustment programmes that pushed for trade and investment liberalisation. It was, however, in the 1990s that most of these policies went into full swing, largely influenced by the “Asian bandwagon” of finance liberalisation, the institutionalisation of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), the conclusion of the GATT-UR, and the generally triumphalist dominance of the neo-liberal ideology. During this period, tariff reduction was done unilaterally beyond WTO-bound rates. State enterprises and assets were privatised starting with government-owned and -controlled corporations (GOCCs), such as Petron Corporation and Philippine National Bank. This was followed by the sale of prime assets, such as the Philippine Estate Authority-Amari estate and Fort Bonifacio; the Build-Operate-Transfer scheme for public works; and the privatisation of water and power/energy utilities. Key sectors and industries were also deregulated–for example, banking, retail trade, capital markets, oil, mining, telecommunications, and other sectors.

Following the Asian financial crisis in 1997, and although the Philippines was not hit as badly as most of its neighbours, the government assumed a considerable chunk of the nonperforming loans owed by major private and public corporations, and resold Philippine debt papers beyond prevailing market prices. This action significantly increased the country’s foreign debt. At present, the country is experiencing a fiscal crisis that is further diminishing public expenditures for basic social services and development efforts. The government’s solution, however, is to burden the people with increased taxes instead of raising tariffs and reviewing its policy on debt repayment and borrowing.

Poverty indicators in the last ten years in the Philippines show a worsening trend, with 40% of Filipinos now living below the poverty threshold. Unemployment rate rose from 8.5% in 1997 to 12% in 2003, despite increases in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), indicating a phenomenon of “jobless growth.” Real wages have also fallen to almost their previous level in 1980.

At a time when real wages are declining, female labour force participation is increasing, especially in the services sector where women traditionally dominate employment in trade, community, social, and personal services. This development impact on poverty, inequality and particularly on women; assess their impact of family well-being and conditions and adjust them, as appropriate, to promote more equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities, income and services.”

The Philippines ratified the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade-Uruguay Round (GATT-UR) in late 1994 and was a signatory to the BPFA in 1995. Prior to these agreements, the country was already implementing, as early as the 1970s, a series of International Monetary Fund (IMF) structural adjustment programmes that pushed for trade and investment liberalisation. It was, however, in the 1990s that most of these policies went into full swing, largely influenced by the “Asian bandwagon” of finance liberalisation, the institutionalisation of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), the conclusion of the GATT-UR, and the generally triumphalist dominance of the neo-liberal ideology. During this period, tariff reduction was done unilaterally beyond WTO-bound rates. State enterprises and assets were privatised starting with government-owned and -controlled corporations (GOCCs), such as Petron Corporation and Philippine National Bank. This was followed by the sale of prime assets, such as the Philippine Estate Authority-Amari estate and Fort Bonifacio; the Build-Operate-Transfer scheme for public works; and the privatisation of water and power/energy utilities. Key sectors and industries were also deregulated–for example, banking, retail trade, capital markets, oil, mining, telecommunications, and other sectors.

Following the Asian financial crisis in 19 97, and although the Philippines was not hit as badly as most of its neighbours, the government assumed a considerable chunk of the nonperforming loans owed by major private and public corporations, and resold Philippine debt papers beyond prevailing market prices. This action significantly increased the country’s foreign debt. At present, the country is experiencing a fiscal crisis that is further diminishing public expenditures for basic social services and development efforts. The government’s solution, however, is to burden the people with increased taxes instead of raising tariffs and reviewing its policy on debt repayment and borrowing.

Poverty indicators in the last ten years in the Philippines show a worsening trend, with 40% of Filipinos now living below the poverty threshold. Unemployment rate rose from 8.5% in 1997 to 12% in 2003, despite increases in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), indicating a phenomenon of “jobless growth.” Real wages have also fallen to almost their previous level in 1980.

At a time when real wages are declining, female labour force participation is increasing, especially in the services sector where women traditionally dominate employment in trade, community, social, and personal services. This development is partly explained by the growth in the services sector (while the shares of industry and agriculture to the GDP were consistently falling) and the need to increase household income (as evidenced in the general decline of the income share of households in GDP). Aside from a general decline in real wages, wages in sectors where women are dominant remain below the average wage rate. It is also in the services sector where economic activities have a higher degree of informalisation, denoting lesser protection of workers’ welfare and labour rights. Even in manufacturing, where the garments and electronics industries predominate in labour employment, of which 7% are women, casualisation (both in electronics and garment factories) and proliferation of home-based work (specifically in garments) characterise the conditions of labour.

The deterioration of public services resulting from the government’s fiscal constraints, coupled by policies of privatisation and deregulation, has intensified the “double burden” of women who straddle between productive and social reproductive work. With increased participation of women in production and the absence of publicly provided services, provision of social reproductive care in the household is replaced by time-saving household appliances or passed on to unpaid female members of the family or to hired domestic helpers.

Trade propensity in agriculture has done little to alter the economic and social status of rural women. Although there may be high demand for labour in export-intensive agriculture, the paid returns to labour are very minimal and often subject to very exploitative conditions. In recent years, as the terms of trade deteriorated for primary exports and cheaper agricultural imports flooded the domestic market, the decline in rural incomes and loss of livelihoods had affected almost all sectors–from food to export crops, to farming, to poultry and livestock.

The “July Framework Agreement” for negotiations approved last year by the WTO General Council basically advances the Doha agenda and puts forth concrete modalities for areas such as NAMA, GATS, and trade facilitation while at the same time justifies the agricultural subsidy regime of developed countries. Parallel to multilateral negotiations in the WTO, bilateral and regional free trade agreements are proliferating, which are more comprehensive as these cover areas such as investments and are outpacing the WTO’s timetable of implementation.

The NAMA modalities, as contained in the “July Framework Agreement,” called for a comprehensive coverage of all products not covered by the “Agreement on Agriculture,” subjecting both bound and unbound tariff lines to tariff reduction and elimination. Once all products are subject to tariff binding, government flexibility in adjusting tariffs as an instrument to pursue specific national development strategies such as protection of an industry from competitive imports, is therefore restricted. Critics aver that NAMA is a recipe for de-industrialisation.

The Philippines submitted bindings for about 2,998 non-agricultural tariff lines (61.8%) and 783 agricultural products (99.4%). Total binding coverage for all products is 66.8% of 5,640 tariff lines. The country’s average bound rate at the Uruguay round for non-agricultural product is 23.4%; and for agricultural products, 34.6%. For all products, the average bound rate of the Philippines is 25.6%. As a general rule, the Philippines bounds tariffs on these tariff lines at a ceiling rate of 10 percentage points above the 1995 applied rate. The actual tariff rates (or applied rates) in 2002 averaged 5.2% for non-agricultural products and 9.2% for agricultural items. Overall average was 5.7%. The low applied tariff rates are the result of the Philippine government’s unilateral “Tariff Reform Programs.” This unilateral act entails no reciprocity from the country’s trading partners, and no credit for this autonomous liberalisation can be demanded based on existing draft of NAMA modalities.

Tarrif bindings

Countries typically impose tarriffs on imported products to protect local industries producing the same products. In international trade, trading countries prefer that tarrifs be "bound" or fixed to a range of rates so that trading is more predictable. However, some developing countries prefer to keep rates unbound so that they can have the flexibility to protect their industries from unfair competition.

Source: Blouin, Chantal and Weston, Ann (2002), "The Reality of Developing Countries"

GATS involves four modes of supplying services, namely:

1. cross-border supply (service crosses national boundaries, e.g., remittances, telecommunications, courier and internet services);

2. consumption abroad (consumer crosses national boundaries, e.g., tourism);

3. foreign commercial presence (sets up shop in another country); and

4. movement of natural persons (to provide service but not to seek employment).

Among these four, Mode 3 appears to be the main thrust of the GATS negotiation, which is essentially an investment agreement.

European Union (EU) requests for the Philippines include professional services ( e.g., accountancy ), business services (including printing and publishing services), postal and courier services, telecommunications services (including electronic data exchange and radio frequencies), distribution services (including franchising), environmental services, financial services (including branching), tourism and related services, news agency services, transport services (air, maritime, land), and energy services (e.g., distribution and construction of facilities).

For the Philippines to comply with the EU requests and GATS in general, it has to amend its Constitution in order to allow foreign ownership of land and real estate, foreign ownership of media and advertising, and a 100% foreign equity in banks. It has to relax citizenship requirements for foreign investors and their personnel and permit the free entry of investors into mining exploration, energy distribution and retailing, transport, and other utilities. GATS, and specifically the provisions on procurement and competition policy, undermines the social dimensions and universal concept of public service since government will have to privatise public service and break its monopoly as provider of key social services.

Gender issues are ignored in GATS despite the fact that women predominate in the service sector and are the ones most exploited by "labour flexibilisation." Prostitution and trafficking are also expected to further rise in unregulated service liberalisation, such as in tourism.

Mode 4 (on movement of natural persons) only involves the movement of technical and managerial personnel of transnational corporations (TNCs) with commercial presence in the host-country and does not, in any way, refer to promoting employment for migrant workers from developing countries seeking jobs abroad.

B.BPFA commitments on macroeconomic and sectoral policies

BPFA Government Commitment 58(c): "Pursue and implement sound and stable macroeconomic and sectoral policies that are designed and monitored with the full and equal participaton of women, encourage broad-based sustained economic growth, address the structural causes of poverty and are geared towards eradicating poverty and reducing gender-based inequality within the overall framework of achieving people-centred sustainable development."

Specific sectors and issues considered to be essential in the review of BPFA vis-a-vis trade and macroeconomic policies formed the main body of the discussions. BPFA commitments pertinent to these sectors were also identified and assessed.

B.1 On agriculture, fisheries and food security

BPFA Government Commitment 58(e): "Develop agricultural and fishing sectors, where and as necessary, in order to ensure, as appropriate, household and national food security and food self-sufficiency, by allocating the necessary financial, technical and human resources."

BPFA Government Commitment 58(n): "Formulate and implement policies and programmes that enhance the access of women agricultural and fisheries producers (including subsistence farmers and producers, especially in rural areas) to financial, technical, extension and marketing services; provide access to and control of land, appropriate infrastructure, and technology in order to increase women's incomes and promote household food security, especially in rural areas and, where appropriate, encourage the development of producer-owned, market-based cooperatives."

In the last ten years, since the inclusion of agriculture in the disciplines of GATT, three trends characterised the terms of trade and overall state of development in Philippine agriculture, namely:

1. import dumping or the entry of highly subsidised, low-priced agricultural surpluses coming mainly from developed countries;

2. import surges or the influx of large volumes of agricultural imports; and

3. withdrawal of domestic support to agriculture.

These trends resulted in huge agricultural trade deficits and unsustained growth in production output, especially in key food sectors (e.g., rice and corn) on which depends a large majority of local farmers. In eager anticipation of the supposed benefits of trade liberalisation, the Philippine government unilaterally reduced tariffs, bringing the nominal average tariff rate in agriculture to 12%, a figure much lower than WTO-bound rates of 30%.

Notwithstanding the fact that developed countries have not been complying with the agreed on rules on subsidy reduction, the WTO "Agreement on Agriculture" is fundamentally imbalanced or biased against developing countries. To cure this imbalance, developing countries must be given the right to develop their agriculture through domestic support and protection from unfair trade and competition with highly subsidised imports from the North. In their history of development, even developed countries, for example, the United States and EU members, employed protection and massive domestic support as key instruments in order for them to reach the level of agricultural development that they have now.

The recent inclusion of fisheries sector under WTO negotiations on NAMA is quite misplaced from the point of view of most developing countries whose fishing industry remains undeveloped, as characterised by small-scale artisanal fishing that employs 50 million of the world's 51 million fishers. Hence, in the event that trade liberalisation is implemented in the fisheries sector, it could easily affect the livelihoods of almost all of the world's fishers.

In the July (2004) framework agreement of the WTO General Council, there is no timeframe for subsidy reduction in NAMA despite World Bank reports that around USD14-20 billion worth of subsidies are poured in by developed countries into their fishing industry. The July framework is also silent on the issue of conservation, implicitly passing the responsibility and burden of conserving fishery resources on communities.

The structural imbalances in world agricultural trade, exacerbated by the Agreement on Agriculture and further still by the coverage of fisheries in NAMA, has limited the capacity of developing countries to achieve both household and national food security and sufficiency. Redefining food security in terms of access to cheaper food imports in order to support arguments for trade liberalisation is not only simplistic but also false. With half of developing countries' population depending on agriculture for their livelihood, food security is an issue, not of food supply but of economic survival; and for the nation-state, an issue of food sovereignty.

B.2 On external debt, privatisation and allocation of funds to public services

BPFA Government Commitment 58(d): "Restructure and target the allocation of public expenditures to promote women's economic opportunities and equal access to productive resources and to address the basic social, educational and health needs of women, particularly those living in poverty."

BPFA Government Commitment 167(d): "Ensure that women's priorities are included in public investment programmes for economic infrastructure, such as water and sanitation, electrification and energy conservation, transport and road construction; and promote greater involvement of women beneficiaries at the project planning and implementation stages to ensure access to jobs and contracts."

BPFA Government Commitment 165(i): "Facilitate, at appropriate levels, more open and transparent budget processes."

BPFA Commitment of WB, IMF and regional development institutions 59(b): "Strengthen analytical capacity in order to more systematically strengthen gender perspectives and integrate these into the design and implementation of lending programmes, including structural adjustment and economic recovery programmes."

BPFA Commitment of WB, IMF and regional development institutions 59(c): "Find effective development-oriented and durable solutions to external debt problems in order to help them to finance programmes and projects targeted at development, including the advancement of women, inter alia, through the immediate implementation of the terms of debt forgiveness agreed upon in the Paris Club in December 1994, which encompassed debt reduction, including cancellation or other debt relief measures, and develop techniques of debt conversion applied to social development programmes and projects in conformity with the priorities of the Platform for Action."

The Philippines national government's total debt stood at PHP3.36 trillion (USD60 billion) as of the end of 2003, split almost equally between foreign and domestic liabilities. This amount is equivalent to 78% of GDP, and eats up 30% of annual spending for interest payments alone. The marked increase by PHP2.01 trillion (USD40 billion), or by almost 200% from PHP1.35 trillion (USD24 billion) in 1997 to PHP3.36 trillion (USD60 billion) in 2003 ostensibly occurred in the last seven years, following the Asian financial crisis. This sharp increase in the national government debt is accounted for mainly by two factors. One is the huge national budget deficits largely also caused by the rising share of debt service in the budget, falling revenue efforts, and spending for salaries, maintenance and operating expenses of the bureaucracy that all leave little room for infrastructure spending and development efforts. Second, and which has been controversial, is the government bail-out and assumption of liabilities and net lending to GOCCs, most of which have been notorious for scandalous deals and graft-ridden contracts, and for serving as milking cows of corrupt government officials. How much of the consolidated public sector debt, which now represents 130% of GDP, would be further assumed by the national government is a matter that has recently invited congressional and public scrutiny.

Such a problem, therefore, makes an argument for privatisation efforts in the public sector.

However, the Philippine experience in privatising public utility services is also a classic case. It does not only defy the widely propagated belief that privatisation brings about efficiency in public service, it also shows that corruption in government could only be equally matched by corporate corruption.

Water distribution and energy/power generation are the first two public utility service sectors that underwent privatisation in the 1990s. Two corporations, owned by the richest families in the country, were granted separate franchises to operate water distribution in the eastern (Manila Water Corporation) and western (Maynilad) sections of the whole metropolitan Manila (covering several cities). The immediate effect on consumers was the unregulated increases in water rate prices without any significant improvement in service delivery. Worse, the government in 2003 was forced to assume the debts of Maynilad (whose indebtedness is on account of its parent company's losses in other businesses), besides not being paid correctly of its franchise fees.

The same is true in the energy sector when, in the early 1990s, several private independent power producers (IPPs) were granted "power purchase agreements (PPAs)" by the government-owned National Power Corporation (NPC) to produce electricity. The PPA stipulated "take-or-pay" clauses that committed the government to pay the IPPs a fixed amount, regardless of whether the NPC sold all the electricity or not. Not only were the contracts overpriced but some of the IPPs are not even operating due to oversupply, and yet they continued to receive payments from government, which were, in turn passed on to consumers in the form of power rate increases. The government-owned NPC is also up for privatisation. But its huge debts, now representing a significant chunk in the government's assumed liabilities, make it a potential candidate for another scandalous deal.

B.3 On women's employment and income

BPFA Government Commitment 58(h): "Generate economic policies that have a positive impact on the employment and income of women workers in both the formal and informal sectors and adopt specific measures to address women's unemployment, in particular, their long-term unemployment."

BPFA Government Commitment 165(a): "Enact and enforce legislation to guarantee the rights of women and men to equal pay for equal work of equal value."

BPFA Government Commitment 165(r): "Reform laws or enact national policies that support the establishment of labuor laws to ensure the protection of all women workers, including safe work practices, the right to organise and access to justice."

BPFA Government Commitment 165(r): "Reform laws or enact national policies that support the establishment of labuor laws to ensure the protection of all women workers, including safe work practices, the right to organise and access to justice."

BPFA Government Commitment 165(l): "Ensure that all corporations, including transnational corporations, comply with national laws and codes, social security regulations, applicable international agreements, instruments and conventions, including those related to the environment and other relevant laws."

BPFA Government Commitment 178(h): "Recognise collective bargaining as a right and as an important mechanism for eliminating wage inequality for women and to improve working conditions."

BPFA Government Commitment 58(k): "Ensure the full realisation of the human rights of all women migrants, including women migrant workers, and their protection against violence and exploitation introduce measures for the empowerment of documented women migrants, including women migrant workers; facilitate the productive employment of documented migrant women through greater recognition of their skills, foreign education and credentials, and facilitate their full integration into the labour force."

As mentioned earlier, trade liberalisation and global economic integration facilitated the increased labour force participation of women. However, women's employment continues to be confined to occupations traditionally dominated by women such as in the service sector, specifically in sales as well as community, personal and social services. However, wages in these occupations remain to be lower than the national average wage rate. The service sector also accounts for economic activities that have a high degree of informalisation.

Aside from increased employment in the service sector, women have also dominated labour employment in the garments and electronics industries, the two major industries in exports manufacturing that were subcontracted to developing countries in the last three decades as part of an internationalised production process. The practice of labour flexibilisation schemes in these two industries has worsened in recent years as the Philippines tried to compete with other developing countries in terms of lower wage regimes and deregulated labour standards.

With the phase-out of the quota regime of the "Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA)" in December 2004 under the terms agreed on in the WTO "Agreement on Textile and Clothing", the Philippine garments industry, which has at least enjoyed assured quota in the U.S. market, faces bleak prospects. The local textile industry has long been dead since the 1980s when cheaper textile imports flooded the local market as the main supply source of garment manufacturers. International subcontracting in the garments industry facilitated such market pattern, where TNCs profited from lower wage regimes in garments manufacturing while controlling the input and output end of the production process.

Eighty percent of workers in garments are women. The industry represents the worse forms of labour conditions like low wages, contractualisation, flexibilisation, non-recognition of trade union rights, and many others-a manifestation of the "race to the bottom" phenomenon among Third World countries competing against one another for their most sought-after foreign direct investments. The Philippines is losing out to Bangladesh, Pakistan and other South Asian countries where wages are much lower. Since the late 1990s, many local garment manufacturers have either closed down or reduced production volumes resulting in massive loss of jobs and more oppressive working conditions. With the elimination of the MFA quota in the U.S., the local garments industry is in a quandary.

B.4 Regulations in the pharmaceutical industry and women's health

BPFA Government Commitment 106(e): "Provide more accessible, available and affordable primary health care services of high quality, including sexual and reproductive health care, which includes family planning information and services, and giving particular attention to maternal and emergency obstetric care, as agreed to in the 'Programme of Action of International Conference on Population Development (ICPD)'".

BPFA Government Commitment 106(u): "Rationalise drug procurement and ensure a reliable, continuous supply of high quality pharmaceutical, contraceptive and other supplies and equipment, using the WHO Model List of Essential Drugs as a guide, and ensure the safety of drugs and devices through national regulatory drug approval processes."

Drug prices in the Philippines are among the highest in the world, and the cost is largely borne by consumers rather than by government and social health institutions. In the country, 44% of health expenditures go the cost of medicines, and social health institutions shoulder only 5% of drug costs. Unlike in India and Thailand where a two-year patenting apply only on the process, in the Philippines, patents are applied also on the chemical composition of a drug. Other profit-maximising schemes of drug companies also contribute to higher costs, such as transfer pricing, promotional incentives to doctors, and "follow-the-leader" pricing.

Notwithstanding the Doha development agenda, which opened up opportunities for some concessions to developing countries on this aspect of access to cheaper medicines, the Philippine government has, in fact, many readily available options at its disposal-if only it has the political will to do so. For instance, the Cut the Cost, Cut the Pain Network has been lobbying the government to fully utilise the PHP65 billion (USD1.16 billion) fund in medical reimbursements that is in the coffers of the Philipppine Health Insurance Corporation, of which only PHP2billion (USD35M) is being used for the said purpose.

B.5 Trade in the media industry

BPFA Commitment of national and international media systems 240: "Develop, consistent with freedom of expression, regulatory mechanisms, including voluntary ones that promote balanced and diverse portrayals of women by the media and international communication systems and that promote increased participation by women and men in production and decision-making."

BPFA Commitment of governments and international organisations 243(d): "To the extent consistent with freedom of expression, encourage the media to refrain from presenting women as inferior beings and exploiting them as sexual objects and commodities, rather than presenting them as creative human beings, key actors, and contributors to and beneficiaries of the process of development."

Cultural products in the era of globalisation are not simply those seen in museums or galleries, the work of artists, books, or knowledge and customs handed down by older generations. Under globalisation, the media has played a central role in influencing people's day-to-day way of life and thinking in various ways, for example, TV, radio, internet, billboards, cellphones, newspapers, and many others. In the WTO, these cultural products and services are those covered in TRIPS as intellectual property, and in GATS as well as those found in bilateral and regional trade agreements as services. Some of the issues involved in the trading of cultural products include: monopoly control of the media (media outfits and producers of computer software and hardware belong to the richest corporations in the world), outsourcing of services abroad where labour is cheaper, and insufficiency or lack of regulations to control content. Monopoly control of cultural products has not only raked in billions of profits for these corporations but has also become their instrument of ideological control, threatening cultural diversity, propagating militarism and the dominance of one race, class, gender, and set of beliefs over the rest of the world.

Recommendations and Campaign Strategies

The synthesis of main points and recommendations that came out in the Forum in December 2004 is as follows:

1. The country's trade and macroeconomic policies in the last ten years have followed the neo-liberal dictum of the WTO and the international financial institutions (IFIs). Prior to 1995, much of the trade and investment liberalisation policies carried out were part of structural adjustment programmes, although some were done (such as the "Tariff Reform Programs") on account of the Philippine government's unilateral attempt to be at pace with the "globalisation bandwagon."

2. There is conflict between neo-liberal economic policies and the human development commitments made by governments and multilateral institutions in Beijing as well as in many other United Nations conventions. Compared to the WTO which is vested with "police powers", the UN Committee on the Status of Women (UNCSW) can only monitor and report on government implementation of the BPFA and use moral suasion to push compliance to commitments. Nonetheless, the BPFA provides a platform for advocacy, especially for civil society, that can be used as a point of reference in pressuring governments and multilateral institutions for its implementation. There is, in a sense, a "convergence and tension" between the WTO and BPFA.

3. The WTO "July Framework" represents still a fragile consensus, especially because the General Council cannot and should not be appropriating the final and plenary powers of the Ministerial Conference. From now on and until the Ministerial Conference in Hongkong in December 2005, efforts should be concentrated on shattering this fragile consensus, and lobbying efforts in Geneva negotiations should be strengthened. And while lobbying is done with trade negotiators in Geneva, comprehensive and coordinated national campaigns should be built up to pressure governments at home.

4. In countries where bilateral and regional free trade agreements are a threat, national campaigns should be stepped up. These campaigns could be coordinated on a regional scale or between people's campaigns in countries involved in bilateral FTAs. Nuances in the power play or competitive positioning of major players in the WTO could be exploited as a potential arena in de-centering the U.S.

5. Particular calls and demands on the Philippine government regarding specific issues that are the subject of current WTO negotiations include the following:

5.1 On NAMA, the Fair Trade Alliance proposes that even as the government is now negotiating for new bound rates that should provide flexibility in tariff setting for the Philippines, it should, in the meantime, avail of existing flexibilities by selectively re-calibrating tariffs on imported products that compete with locally manufactured goods. This call also fits well with the need to raise revenues from tariffs to address the country's current fiscal crisis.5.2 Also on NAMA, fishers' organisations in the Philippines have called on government to retain the law (Republic Act 8550) banning the sale of fish imports in wet markets and supermarkets to provide domestic subsidies for small-scale fishers and to retain the quantitative restrictions (QRs) on fisheries. While ultimately demanding to get fisheries out of NAMA, these organisations also support calls to input "externalities" in fishery-product costing and to count non-implementation of laws as "implicit subsidy."5.3 On agriculture, the demand is to retain the QR on rice and raise the unilaterally reduced applied tariff rates on agricultural products to the maximum bound rates in the WTO. The flexibilities on subsidy reduction given to developed countries in the WTO July Framework should be opposed while supporting the efforts of developing countries to push for concrete modalities on special and differential treatment.5.4 On GATS, the myth that Mode 4 could promote the employment of migrant workers from developing countries should be shattered while concentrating the attack on Mode 3 as the real and main agenda of developed countries in GATS, which basically is an investment agreement.

6. As the BPFA's implementation is reviewed in its tenth year and WTO negotiations heat up leading to the Hongkong Ministerial Meeting, women's campaigns and mobilisations in the Philippines are set to focus on issues and demands around poverty and economic globalisation. The year-long and nationwide campaign, dubbed "Women's March Against Poverty and Globalization" kicked off on March 8, 2005 (International Women's Day) and will culminate in December during the WTO Hongkong Ministerial Meeting in the form of a nationally coordinated mobilisation march of around half a million women in all the major cities of the country.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.