Political Violence, The State and the Anti-State

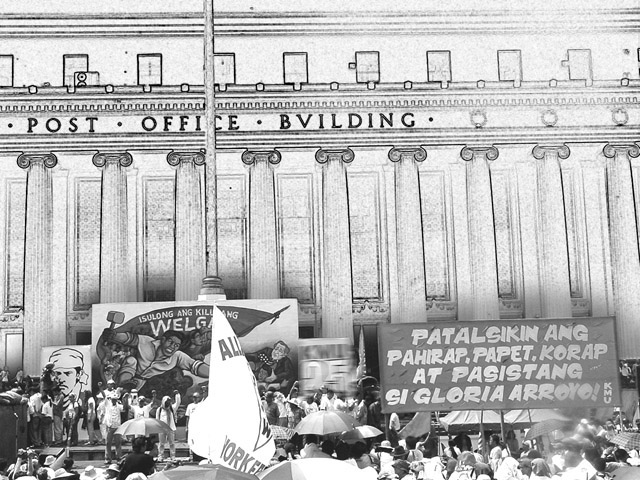

This paper discusses the Philippine context of a state facing off with socialist revolutionary groups threatening its power. However, the typical solution is violence, specially now that the government’s anticommunist stance is now re-stated as anti-terrorism. Meanwhile, anti-state forces also use violence to challenge state power.

For centuries, national security options of states straddled between two approaches: one based on power, the other based on peace. The first option, power, may be better said as “power over” or the principle of domination over the groups posing a challenge to the state—its policies, actions, and more fundamentally, its nature. “Power over,” at the minimum, aims to neutralise, and at the maximum exterminate, eliminate, subjugate contending forces in the name of the state and its desired attributes— sovereignty, stability, survival. At a glance, this approach seems to be the only logical option for a weak state, whose very weakness forces it to make a show of being strong.

The second approach is peace—that is, to seek peace as a precondition to and/or an outcome of security. This approach is founded on the core values of tolerance, pluralism, and dialogue, the exact opposite of the values in the first approach: intolerance, exclusivity, brute force and monologue. It involves statebuilding through much needed reforms. Its guiding principle is “do no (more) harm” to the situation as it is.

Collective impact measures

What we have been witnessing in the Philippines in the last years is an internal security approach founded on the state’s attempt to dominate and subjugate critical socio-political forces. Its guiding principle is precisely to “do harm”. It incorporates the usual military operations against communist guerillas operating in the countryside. Such an approach relies heavily on the Philippine army entailing the participation of state agencies.

Reports of de facto curfews, arbitrary searches, harassment, imposition of the cedula, and mopping up operations, reflect that the classic counter-insurgency approach of draining the fish of its water continues. To suffocate the fish, the water is contained, drained or rendered unable to resist military pressure.

These methods have been referred to as “collective impact measures.” This type of measures intends to hurt the populace in order to render them submissive. A local resident who gets killed in the process is seen as collateral damage to the intent.

Collective impact measures also function as “collective punishment.” Residents are scolded and threatened for acts deemed sympathetic to the enemy. In general assemblies recently held in Central Luzon by the military under General Jovito Palparan, a former commander of the Philippine Army, residents are beseeched and courted, entertained with songs and sexy dancers in exchange for their sympathies. They are urged to speak out despite the asymmetry in the situation: unarmed, poor farmers facing fully armed lieutenants, colonels, and generals. But when they speak out and complain of abuses of government soldiers, they are reprimanded and accused of being “influenced” by the insurgents or by being members of the New Peoples Army (NPA). They become the brunt of displaced aggression, the easy target of traumatised soldiers faced with elusive “enemies.”

The society endures a high level of criminal violence, and delivery of socioeconomic goods is limited. Its institutions are flawed; its infrastructure, deteriorating or destroyed.

The unprecedented high number of killings of political activists in the Philippines associated with national democratic organisations as well as other left-wing groups in compressed time is part of this “collective punishment” frame. The extrajudicial killings share the same features of rural community-based counter-guerilla warfare: indiscriminate or dismissive of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, and clouded by “hate language” and demonisation of the enemy. A slight difference is that the killings are somewhat disguised: they are not done by men in military uniform, whereas the usual counter-insurgency is marked by troops descending in communities who seek security and cover in numbers.

The killings’ desired impact is the same: fear, paralysis, scuttling of the organisational network, albeit not just in the local but the national sense. The goal is to break the political infrastructure of the movement whose good showing in the past election under the party list system and corresponding access to pork barrel funds were, from the point of view of the anti-communist state, alarming. National politics is after all the bigger pond where the fish swim. But here the instructions are straight to the point: kill the fish.

In this power-based approach manifested in collective punitive measures, victory is easy to measure. One is through body count: how many are dead and wounded? Another is through weapons count: how many weapons were seized? The final measure is on the number of communities, organisations, and people neutralized.

Collective impact measures create more problems due to the social tensions and resentment they generate in the communities and the affected public. They erode the fabric of society, confuse its norms, polarise, and desensitise. They provide fodder to counter-violence, and diminish faith in the system and peaceful change. They are sure-fire formulas for greater violence. They are our own “low-tech” version of weapons of mass destruction which nonetheless leads to the same MAD-ness or “mutually assured destruction.” The victory they lay claim is short-term, flaky, and one sided.

Multi-Layered Contexts

There are multi-layered contexts on this intensified state violence against a certain social force, its various apparatuses, but ultimately, violence or assault on the citizens at large.

One context is the short term: President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s (GMA) political survival.

The long and short of this context is the legitimacy question raised against her administration. Here, the national democratic left has played a major role, whether in the attempts at setting off an impeachment process or in military coup-cum-street protests that will force GMA to step down. The national democratic left has also put blocks to attempts of the government to strengthen its emergency powers or insulate the presidency from the checks powers in the hands of Congress and the citizens.

It is to the GMA presidency’s interest to weaken the multiple machineries of the national democratic left through both judicial and extra-judicial means. It is to GMA’s interest to reward the loyalty of key state players crucial to her political survival, notably, the military, the police and the members of Congress. It is in her interest to join the “coalition of the willing” and the US-led global fight against terrorism in order to get the backing and material support of US President Bush. In this regard, the GMA administration actively lobbied for the inclusion of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP)-NPA in the list of terrorist organisations of the US and European bodies – even though the CPP-NPA does not as a rule employ terrorist methods like bombings.

But beyond the GMA presidency is the state of affairs of the Philippine state – the more important, larger context. This is a question that will transcend GMA, and is related to but distorted by the partisan peddling of charter change. This is the specter of not just a weak state but of a disintegrating, failing state, one where governance increasingly becomes unstable and short-sighted, and reforms impossible. The prospects of a failed state result from the transgressions of the Marcos administration that the country has inherited and how its political elites have selfishly played their games in this situation. It is the bigger context where the wanton use of state violence by both civilian and political leaders, and the military’s privileged role in national security and national politics have become even more ominous.

This is the specter of not just a weak state but of a disintegrating, failing state, one where governance increasingly becomes unstable and short-sighted, and reforms impossible.

What is a failed state? Rotberg (2004) describes it as one marked by enduring violence, though not necessarily always of high level of intensity. It is tense, deeply conflicted, dangerous and contested bitterly by warring factions, with varieties of civil unrest and two or more insurgencies, different degrees of communal discontent and other forms of dissent directed against it and at groups within it. Parts of the territory, notably the peripheral regions, are not under its control. There is a high level of physical insecurity among citizens, thus they are armed or they join rebel groups. The society endures a high level of criminal violence, and delivery of socio-economic goods is limited. Its institutions are flawed; its infrastructure, deteriorating or destroyed.

The more recent line from General Palparan, said over one television program recently, is almost a tacit recognition of the situation of the Philippines as a failing state. Only in such a state can his explanation for the killings make sense. According to Palparan, the killings are perpetuated by people taking vengeance on the NPA for the latter’s abuses. Queried if these people include soldiers, he replied in the positive, saying such soldiers are probably taking revenge for the death of other soldiers. If the state were a viable state, can this kind of anarchy and lame excuse be palpable?

Anti-communism and anti-terrorism

Anti-communism as the ideological foundation of and justification for the state’s excessive use of violence remains. The language of anti-terrorism adds a new, more contemporary twist, and locates domestic wars in the context of the post-9/11 world order.

The language of anti-communism remains effective, given a general antipathy to communism, and an increasing alienation of the citizenry to national politics. To those who have fallen for this anti-communist “rhetorical hysteria,” the killings are not a case of “slaughter of innocents” given that these people are somehow allied with the CPPNPA. They do not think much about the fact that slaughter remains slaughter; that the basic principle of respect for human life and human dignity is for everyone, including the enemy number one of the state, and yes, including terrorists; that there are rules even in war that must be followed, notably distinction between those who carry arms and those who do not. Meanwhile, business executives and professionals may be morally aghast at the unabated killings of alleged communists, but are not motivated enough to put pressure to stop it, until somehow, it starts hurting their economic interests, or their immediate environment. The middle class will continue to fight for their own means of survival regardless of the course of Philippine politics.

However, class analysis alone cannot explain part of the lingering potency of anti-communism. Part of the effectiveness of the language of anticommunism and resultant alienation is also due to the CPP-NPA-NDF themselves—their excesses such as the revolutionary taxation of rich and poor and infliction of punishments; own pandering of violence and machismo; their inclusivity and dogmatic framing of Philippine society and politics; and their counter-monologue to the state’s anti-communist mantra. The purges of the 80s and 90s where the CPP killed members suspected of being deep penetration agents cannot be simply forgotten without full retribution and honest accounting before former and present comrades and the greater public. The ghosts of murdered comrades will haunt the party forever. And though not particularly convincing to explain away the recent spate of political killings among those who study their politics, and revolting for the disrespect shown the dead lying in mass graves, the purges of the 80s and 90s will remain scraps to poke around with, in the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and police forces’ operations against the insurgents.

In all, taken in the context of an untransformed state and reform-resistant state elites, the language of anticommunism coupled with anti-terrorism is actually anti-left. Thus while many human rights and peace advocates have differences with the communist left and oppose terrorist methods, these advocates cannot tolerate the rhetorical hysteria of anti-communism/terrorism. They cannot be unconcerned with the killings of branded communists/terrorists.

Ways Out

What, then, is the central political question of today? During the martial law regime and even during People Power 2, the answer seemed simple enough: Marcos, in the case of the former, and Joseph Estrada, in the case of the latter. Today, the Philippines has to find the answers beyond GMA.

The Philippines must resolve how to deal with armed challenges faced by the state: resolution through conquest of power by a dominant force using force, or through sustainable, inclusive peace through peaceful means. The state has been pursuing the former; it is time to put more stake in the latter. But this can only be done if critical mass is achieved in forcing the state to take this direction.

Civil society must work for a sustainable change founded on human rights and dignity—or a peace process alongside pursuit of specific reforms. There are key critical areas where state reforms are needed and where civil society should spread out and simultaneously intervene: reform of the electoral institutions and processes; reform of the security sector  like the cleansing and professionalisation of the military and police; enhancing governance processes such as the depoliticisation and upgrading of the bureaucracy, strengthening of local governments leading to greater autonomy; and putting more resources in the educational system so that education is provided for all, and it is the kind of education where the values of human rights and peace are at the core.

like the cleansing and professionalisation of the military and police; enhancing governance processes such as the depoliticisation and upgrading of the bureaucracy, strengthening of local governments leading to greater autonomy; and putting more resources in the educational system so that education is provided for all, and it is the kind of education where the values of human rights and peace are at the core.

Correspondingly, counter-violence as the better or best way to fight state violence cannot be accepted.

The Philippine society is festering in a culture of violence—violence that begets violence that dehumanises the victims and the perpetrators, reduces all forums to monologues, and elevates killing to the status of a national sport. The country finds in its midst self-righteous protagonists out to lay claim to their rights while blinded by their dogma and politics to the rights of others. There is much to untangle in the orthodoxy of class antagonism, of class struggle being necessarily violent, the state being the instrument of the ruling class, and the primacy of armed struggle in achieving political change. There is much to question about the soundness of the Maoist injunction to encircle the cities from the countryside as the route to revolutionary victory, of the national democratic revolution as a stepping stone to a socialist revolution. Certainly, people should discuss and debate these but not kill each other.

There should be a discussion on how to reach some national consensus to best achieve social and political change. Without a shared norm or ground rules, and a consensual road map, the Philippines is doomed as a nation.

The campaign against political killings of leftwing activists requires focused, casespecific response directed against the perpetrators and their chain of command. It also compels citizens to ask hard questions about the national security orientation and national security policies of the state and concerned agencies.

Hence, advocacy should be extended to become a campaign for a peace process; a movement against political violence as a whole, promoting human rights and extracting accountability from all parties; a dialogue for norms founded on lifeaffirming means and ends; a national quest for peace built on respect for human rights.

Human rights, peace, and development workers, students and other groups should come together to work for new politics, the kind of politics that makes a firm stand against political violence.

References:

Buzan, Barry. 1983. People States & Fear, The National Security Problem in International Relations. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Rotberg, Robert . 2004. When States Fail, Causes and Consequence. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Soyinka, Wole. 2004. Climate of Fear. London: Profile Books Ltd.

Stepanova, Ektarina. 2003. Anti-terrorism and Peace-building During and After Conflict. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.