In this issue of WIA, women farmers and indigenous women, rural and urban poor women, women fish workers, women organisers and activists speak about the impact of the global food crisis on their lives and communities.

They describe how the crisis has aggravated already difficult situations of poverty and how it has been made worse by climate change, the global financial crisis and ever-decreasing access to land and natural resources.

They describe how the crisis has aggravated already difficult situations of poverty and how it has been made worse by climate change, the global financial crisis and ever-decreasing access to land and natural resources.

These women, from all corners of the world, also speak about how they are meeting the challenges of the crisis in creative ways. They share their strategies, struggles and solutions for overcoming the crisis. Their responses range from survival strategies and coping mechanisms to empowering initiatives.

These initiatives are not the “success stories” or “best practices” of development projects and programmes. They have arisen from the ground up, from women and their communities themselves. Many of these initiatives point to long-term alternatives for their communities that could be adopted on a wider scale.

While the voices of these women are the heart of this publication, this WIA also presents analyses and perspectives on key issues surrounding the food crisis. Several articles propose macro-level alternatives to the neo-liberal economic models that have brought on the crisis.

The opening article, “Inseparable: The Crucial Role of Women in Food Security Revisited,” looks at one of the root causes of the food crisis: lack of knowledge and insufficient promotion of women’s essential contribution to food security. The article ends with the demands of the women farmers who participated in the Rural Women’s Workshop co-organised by Isis International at the time of the World Food Summit in 1996. If the demands of these women farmers had been listened to and acted upon earlier, the food crisis might not have hit women and their families so severely.

In these pages, women from Africa, Asia, Latin America and North America describe how the food crisis is affecting women worldwide. We present a particular look at how it is affecting indigenous women in different parts of the world. These descriptions also give a glimpse of the determination of women in these situations to meet and overcome the challenges of the food crisis.

This issue of WIA also presents provocative critiques of the orthodox account of the food price crisis, of trade agreements and of biofuels. An article on the Gift Economy presents an alternative to patriarchal capitalism. This issue is also a first for Cai Yiping as Isis International’s executive director. She shares the challenges of the food crisis for mainland China.

We thank all those who took the time out of their busy lives, struggles and activism to contribute their stories, examples, critiques, views, perspectives and responses to the food crisis. We also thank all those who interviewed women at the grassroots and translated their stories from local languages and dialects. We are grateful to the Asian Farmers Association for Sustainable Rural Development (AFA) for further linking us with farming communities in the Asian region as well as to Verso Books for allowing us to publish excerpts of Walden Bello’s upcoming provocative book, Food Wars.

The voices we present here come from many different countries around the world, including Argentina, Armenia, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Chile, Ecuador, Fiji, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Laos, Nicaragua, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, the USA, and Vietnam.

We place these articles before you in the hope that they will make a difference.

| Marilee Karl |

| Guest Editor |

EditorialThis issue of WIA features and analyses the impact of the food crisis on women, especially poor rural women, women farmers and fish workers in the global South. The dominance of grassroots women’s views on the crisis, testimonies on their lived experience, reflection on their struggles and hopes in their initiatives are extremely valuable and crucial. This, as much of the analyses on the crisis have come from a rather academic and economistic perspective.

EditorialThis issue of WIA features and analyses the impact of the food crisis on women, especially poor rural women, women farmers and fish workers in the global South. The dominance of grassroots women’s views on the crisis, testimonies on their lived experience, reflection on their struggles and hopes in their initiatives are extremely valuable and crucial. This, as much of the analyses on the crisis have come from a rather academic and economistic perspective.

The challenge then is how we can go beyond this crisis:

How can we transform these women’s voices from different corners of the world and integrate their visions into policy processes at the international, regional, national and community levels? There is still little information on the impact of policies and emergency measures being implemented by the goverments on women. We must think of further demands and measures to ensure that women’s needs and concerns are being addressed, that their voices are being heard, that their initiatives are considered in the planning and implementation of policies and coping mechanisms.

In this globalised world, no crisis can occur on its own and can be solved without a holistic set of strategies.

Fortunately, several articles in this issue of WIA contribute insightful analyses on the inter-linkage of the food crisis with other compounding crises such as the economic, climate and energy crises and its implication on women and the latter’s access to social justice. However, there are some issues which are equally important to further discuss and address as these are likely to be aggravated by the food crisis: the right to food in situations of armed conflict and in contested territories. It is hard to imagine how food security can be achieved while some women are raped or even killed on their way to farmland so as to feed themselves and their families.

We thank all those who shared their stories, critiques and perspectives on the food crisis. We also thank our guest editor and Isis International’s co-founder Marilee Karl, who has been passionately working on this issue, among many others for decades. Their contributions have made this issue of WIA truly empowering.

| Cai Yiping |

| Editor-in-Chief |

Whatever happened to the pledges of world leaders to reduce the number of hungry in the world?

Hunger is on the rise. A food crisis is hurting the poor all over the world, hitting the landless and women the hardest. It struck even before the current global economic meltdown and rising food prices aggravated people’s access to food. Those who were already food insecure find themselves in worsening conditions. They are joined by millions more of newly food-insecure people.

Misguided agricultural and trade policies have contributed to the current food crisis, including the failure to recognise women’s crucial roles in agricultural production and household food security.

Now that we are at the crux of compounding crises, what lessons can we draw? More importantly, how can we avoid the same mistakes in the future?

As the 2008 State of Food Insecurity reported, “The vast majority of urban and rural households in the developing world rely on food purchases for most of their food and stand to lose from high food prices. High food prices reduce real income and worsen the prevalence of food insecurity and malnutrition among the poor by reducing the quantity and quality of food consumed.”

Promises, promises, promises

In the hopeful days of 1996, heads of governments gathered at the World Food Summit (WFS) in Rome, Italy and declared: “We pledge our political will and our common and national commitment to achieving food security for all and to an ongoing effort to eradicate hunger in all countries, with an immediate view to reducing the number of undernourished people to half their present level no later than 2015.” In terms of numbers, this meant reducing the undernourished people in the world from 800 million to 400 million by 2015.

The Milennium Development Goals (MDGs) also pledged to reduce hunger by 2015, but the goal was more modest. MDG 1 is committed to halve the proportion of hungry people rather than the absolute number.

More than halfway towards 2015, the world is nowhere near to approaching the targets of the WFS and MDGs. On the contrary, hunger is increasing around the world. By mid-2008, the number of malnourished people in the world had risen to 923 million, according to the most recent estimates of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The sharpest rise came in 2007 with an increase of 75 million hungry since the period of 2003 to 2005.

Asia-Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 750 million of the hungry people in the world from 2003 to 2005. As a result of the global food crisis, an additional 41 million people in Asia-Pacific and another 24 million in sub-Saharan Africa have plummeted into hunger (FAO, 2008). But no continent or country has been spared. In the United States (US), for instance, more than 38 million people were struggling to put food on the table as of 2006 (Learner, 2006).

Food security? Right to food? Food sovereignty?

The WFS declared that: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life.”

Since the WFS, there has been a groundswell of support especially from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other civil society organisations (CSOs), to recognise the right to food as a human right. NGOs and CSOs, including people’s and peasant’s organisations have rallied around the concept of food sovereignty as essential for food security.

Back in 2001, when governments gathered to assess their progress vis-a-vis their WFS commitments, NGOs and CSOs declared: “Food Sovereignty is the RIGHT of peoples, communities, and countries to define their own agricultural, labour, fishing, food and land policies which are ecologically, socially, economically and culturally appropriate to their unique circumstances. It includes the true right to food and to produce food, which means that all people have the right to safe, nutritious and culturally appropriate food and to food-producing resources and the ability to sustain themselves and their societies” (International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty, 2001).

Availability vs. accessibility

Development agencies often focus on the availability of food through increased food production. Immediately after the WFS, there was an emphasis on improving yields and high-potential productive areas to achieve and maintain sufficient food production to feed the growing world population. Research, technology and a “new green revolution” were seen as the main ways toward food security. This was a continuation of the focus by development agencies on commercial agriculture and cash crops for exports.

Hunger, however, is very much a problem of unequal access to food, both within and among countries. The availability of an adequate supply of food to feed the world’s population at the international level does not mean food security at the national level if a country cannot grow, purchase or otherwise obtain food to feed its people. Likewise the availability of food at the national level does not guarantee food security for all people in the country.

As a result of the global food crisis, an additional 41 million people in Asia-Pacific and another 24 million in sub-Saharan Africa have plummeted into hunger.

Even within households, there are disparities in food security: women and girls get less food than males, both in absolute and nutritional values. The World Food Programme (WFP) revealed: “Gender inequality is a major cause and effect of hunger and poverty: It is estimated that 60 per cent of chronically hungry people are women and girls [and] 20 per cent are children under five.”

Hunger in the midst of abundance

In countries with a super-abundance of available food, people are still going hungry because they do not have access to that food. This is true even in rich countries like the US where over 30 million people, or more than the entire population of some countries, lack enough and sufficiently nutritious food.

In less rich countries, there are also huge gaps between the rich, who can afford to eat sumptuously, and the poor who starve.

Small farmers and peasants squeezed out and hungry

Advocates of the right to food and food sovereignty attribute rising hunger to the promotion of big agro-industrial corporations and the international trade in food and its detrimental effects on local and national food production, especially small farmers. According to the NGO Declaration at a recent high-level meeting on food security in Madrid, Spain, “As the vicious food price crisis deepens,...millions of peasants will be pushed out of food production, adding to the hungry in the rural areas and the slums of the big cities.”

In a statement made by peasants, farmers, NGOs and CSOs at the Madrid meeting in 2009, they asserted: “Peasant-based agriculture and livestock-raising and artisanal fisheries can easily provide enough food once these small-scale food producers can get access to land and aquatic resources and can produce for stable local and domestic markets. This model produces far more food per hectare than the corporate model, enables people to produce their own food and guarantees stable supply.”

Green Revolution

With the increasing incidents of hunger and dependency on food aid in the Southern hemisphere in the middle of the 20th century, governments, donor agencies and other international organisations collaborated on more intensive research on plant varieties and later promoted the proven high-yielding seeds and farming methods, including the heavy use of fertilisers. Such collaboration resulted in the huge volumes of yields especially of rice and wheat in the following decades. By 1968, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Administrator William S. Gaud described this phenomenon, “green revolution.”

The decline of poverty and increase of incomes in Asia were attributed to the green revolution. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) claims that the absolute number of poor people fell from 1.15 billion in 1975 to 825 million in 1995 while real per capita incomes doubled in Asia between 1970 and 1995.

However, the green revolution is also blamed for environmental degradation as well as income inequities. The heavy use of fertilisers has driven away fishes in the rice fields. High yielding varieties were working only in well-irrigated areas. Bigger farms also have greater access to these varieties and corresponding techniques than small farmers.

As Paul Goettlich remarked: “While there can be no argument that the ‘Green Revolution’ created major increases in shear quantity, it’s been a major disaster for efficiency, quality of life, productivity, and the environment. The norm today is monoculture farming, which is founded on highly flawed logic -- massive plots of thousands of acres planted with one highly inbred crop that is drowned in highly toxic chemicals and managed by behemoth machinery. Small traditional farmers around the world are being driven into bankruptcy and worse.”

Sources: Goettlich, Paul. (10 October 2000). “Green Revolution: A Critical Look.”

More food choices or less?

At first glance, it may seem that today’s markets offer more food choices. Supermarkets in rich countries and even in poor ones are stuffed full of food products flown or shipped in from all over the world, leaving great carbon footprints in their wake. You can buy mangoes in Norway and apples in the Philippines. You can find Coca-Cola just about everywhere in developing countries. On the other hand, you may not be able to find locally grown fruits because all the best ones have been exported to richer countries. Some nutritious local foods are disappearing as they are replaced by commercial crops and imported foods.

Similarly, fast food restaurant chains are ubiquitous not only in rich countries but increasingly in poorer ones, often putting local food vendors out of business.

The freedom of choice is on the decline due to the increasing agribusiness control of what is and what is not grown, exportoriented agricultural policies, the decline in biodiversity, and the dominance of transnational mass media which promote certain lifestyles and food. In Madagascar in early 2009, for instance, thousands of local farmers were protesting the plan to allow a 99-year lease of 1.3 million hectares of agricultural land to the South Korean corporation, Daewoo for corn and palm oil cultivation for export to South Korea. This would displace farmers who cultivate red rice, vanilla and other indigenous crops and who are part of the local Terra Madre food communities that promote local organic food production.

Women’s Multiple Roles in Food Security

Women play important roles in food security as food producers, keepers of traditional knowledge and preservers of biodiversity, food processers and preparers and food providers for their families. Because of their multiple roles, women are key players in overcoming food insecurity.

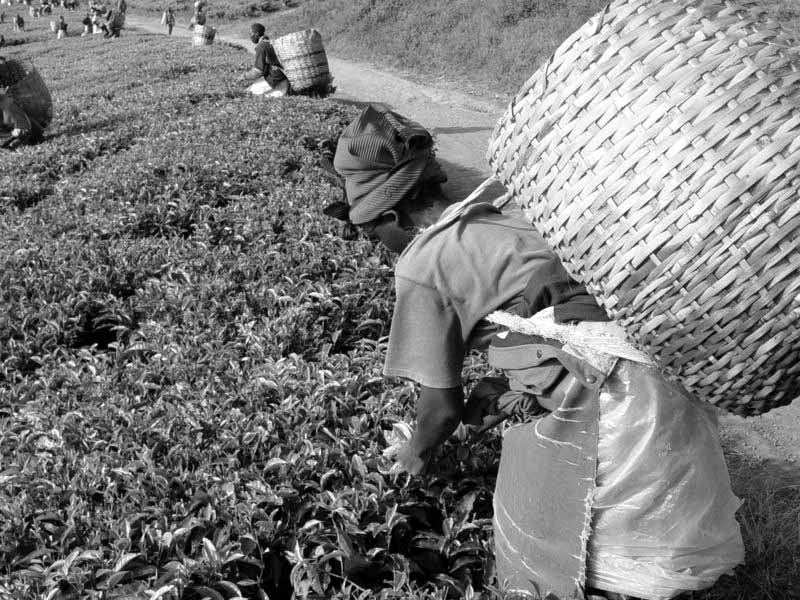

Women as farmers and food producers

Women produce a large part of the world’s food. Exact data is very hard to come by but FAO estimates that women are the main producers of the world’s staple foods: maize, wheat and rice. Overall, women are responsible for about 50 per cent of the world’s food production and, in some countries of sub-Saharan Africa, women provide between 60 and 80 per cent of the food for household consumption, mainly as unpaid labourers on family plots.

Women’s contribution to agricultural production varies from country to country, crop to crop and task to task. In Southeast Asia, women provide up to 90 per cent of the labour for rice cultivation. In Colombia and Peru, women perform 25 to 45 per cent of agricultural field tasks. In Egypt, women contribute 53 per cent of the agricultural labour. Men are found more often in agricultural wage labour and cash crop production, while women are mostly found producing food for their families and local markets.

Women are also found in agricultural wage labour. In Northwest Brazil, for example, women make up 65 per cent of the field workers in vineyards. In Chile, women comprise 60 per cent of the contractual workers in the fruit sector. In Sinaloa, Mexico, women are 40 per cent of the field workers for vegetables and 90 per cent of the packers. In Kenya, women provide 70 to 80 per cent of the labour in packing, labeling and bar-coding of horticulture.

Women perform many tasks in household crop production, including sowing seeds, weeding, applying fertilisers and pesticides, and harvesting and threshing of the crops. They are also responsible for post-harvest food processing, storage, transport and marketing. In addition to producing staple crops, women in many countries also grow legumes and vegetables to feed their families.

They also play an important role in raising poultry and small livestock such as goats, rabbits and pigs. They also feed and milk larger livestock. Their tasks vary from country to country: Latin American women are less involved in crop production than women in sub-Saharan Africa, but are largely responsible for small livestock. In Nepal, women have almost the sole responsibility for fodder collection for buffalo while in Pakistan, women provide the majority of the labour for cleaning, feeding and milking cattle.

Exact data is very hard to come by but FAO estimates that women are the main producers of the world’s staple foods: maize, wheat and rice.

Women likewise assume significant roles in forestry, planting and caring for seedlings and gathering forest products for fuel, fodder and food. With most rural areas dependent on fuel wood, women are almost always the ones responsible for gathering fuel wood that is used not only for cooking but also for food processing and other basic needs such as warmth, light and boiling water for drinking.

Small-scale fisheries, which provide more than 25 per cent of the world’s fish food catch, depend on women’s contributions. In most parts of the world, women in fishing communities catch fish with nets and traps and by baiting and diving. They raise fish and crustaceans; make and repair nets and traps; assist men with launching and beaching operations, sorting and gutting the haul; and process and market their catch.

Women as preservers of biodiversity

Women are often the preservers of traditional knowledge of indigenous plants and seeds. As the ones responsible for supplying their families with food and care, they have a special knowledge of the value and diverse uses of plants for nutrition, health and income. They grow traditional varieties of vegetables, herbs and spices in their home gardens. Women also often experiment with and adapt indigenous species. They are involved in the exchange and saving of seeds. This has important implications for the conservation of plant genetic resources. Unfortunately, the importance of women’s knowledge and expertise on biodiversity is often overlooked or ignored by development planners.

Indigenous women of Chile know the value of biodiversity and ancestral knowledge. The National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women of Chile, Anamuri, has run a Seed Campaign since 2002, with activities that include seedbeds, seed exchanges, biodiversity fairs and ecologically-friendly farming groups, who grow their own vegetables (Alordo, 2008).

As providers of basic foods, fuel and water for their families, women have an important stake in the preservation of the environment and combating environmental degradation. Women recognise the importance of forests as a source of food, fodder, medicine and many other products. Mainly responsible for providing water for the household, women are acutely aware of the importance of water sources. Consequently, women have a particular interest in natural resource management, sustainable development and preservation of the environment.

Villages in the hilly areas of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, India depend on forests for basic needs like water, firewood and fodder. As managers of these natural resources for their families and communities, the women have taken an active role in conserving them. Alarmed by the deforestation of the area which had led to floods and landslides, the women of Dasholi Village began a non-violent protest in 1976, acting as human shields to prevent trees from being cut down. This has grown into an ongoing natural resource conservation movement and spread throughout the whole area. The women first mobilised women’s groups in neighbouring villages and other districts in the region, involving all women and men of the communities which were coordinated by an organisation called the Dasholi Gram Samaj Mandal. These women and their communities have succeeded in regenerating the forests, reducing the damage from floods and landslides and making their own work and lives easier (ISDR, 2008).

Women as food processors, preparers and providers

Women are universally responsible for food preparation for their families and engaged in various stages and steps of processing this food. In many cultures and countries, women have the main responsibility for the provision of food—if not by producing it, then by earning income to purchase it. This applies to urban and non-farming women as well as women farmers, and is not limited to the large percentage of female-headed households in the world.

This gender division of responsibilities is often unrecognised by development planners. False assumptions about households as a unit can have detrimental effects on food security.

Development planners often assume that the increase of household income through the employment of men in cash crop production will benefit everyone and enable the household to purchase food. But in many cases, incomes are not pooled although women remain responsible for supplying the food. A classic example is Central America, where sugar cane was introduced as a cash crop employing men. The result was increased money in the community, but increased malnutrition as well. As men were no longer available for clearing land, women cultivated smaller plots of food crops for their families. The cash earned by men did not go to the purchase of food and everyone in the community suffered greater food insecurity.

Chile: Saving the roots of biodiversity— Women farmers promote ecologicallyfriendly farming and seed preservation*

by Rocío Alorda

Faced with increasing monoculture and use of genetically-modified crops, Chile´ s campesinos are fighting to preserve their ancestral seeds by protecting them from disappearing or becoming contaminated by transgenic varieties.

Since 2002, the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women of Chile, known as Anamuri, has run the Seed Campaign, which includes campesino seedbeds, seed exchanges and biodiversity fairs.

Jacqueline Arriagada, a leader in the Quillon community in the Bio Bio region has fought hard to protect local food sovereignty and ancestral seeds. Rural women´s organisations are defending local and regional biodiversity. The women participate in ecologically-friendly farming groups, where they grow their own vegetables. The organisations are mainly composed of women, for which healthy food for our families is, without a doubt, a great concern,” says Arriagada.

As a response to large-scale industrial food production, many organic crops have sprouted up in these communities, producing clean, safe and environmentally-friendly crops.

Francesca Rodríguez, Anamuri’s director, denounces “biopirates” or foreign companies that are stealing campesino farming methods. Campesino movements and international biodiversity defense movements have identified a series of biopiracy groups that travel the world patenting ancestral seeds from rural and indigenous communities.

“What is developing now is ecological farming, which is nothing more than ancestral farming, recovering forms of farming from our ancestors and continuing to develop them and combine them with new practices because agriculture has never been static, and has always been in a state of evolution,” Rodríguez says. These methods produce safe and healthy foods, work with the land, not simply exploiting it, and are also chemical-free.

In this way, Chile´s rich biodiversity is being protected by those who have traditionally lived off of it and treated it with respect.

*This is a condensed version of the article by the author, orginially published in Latin American Press. (12 October 2008). URL: http://www.latinamericapress.org/ articles.asp?item=2&art=5769

Moving beyond gender analysis Gender analysis is a tool that development agencies began using in the mid-1980s to find out more precisely the roles and tasks of women in agriculture in relation to those of men. Previously, most agricultural development projects and resources were directed to men on the assumption that men were the principal farmers. Women were assumed to be responsible only for food preparation and so they became the recipients of nutrition and home economics programmes.

Gender analysis shows that the men and women in food production vary from place to place. Often they are complementary, with men and women sharing or dividing tasks in the production of certain crops. Sometimes men and women have distinct tasks or responsibilities for different crops or livestock. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, men on the whole perform about 90 per cent of clearing the land and 75 per cent of turning the soil. Planting and caring of domestic livestock are shared about equally by men and women. Women are responsible for 60 to 80 per cent of hoeing, weeding, harvesting, transporting, storing and marketing of produce. Women also perform 90 per cent of food processing, fuel and water collection. They are virtually 100 per cent responsible for feeding the family.

New understandings about gender and gender mainstreaming

Gender analysis alone is insufficient to enable women to optimise their contributions to food security. Gender perspectives – the views of both women and men – must be taken into account. Women must have the opportunity to express their views and bring their perspectives into development and food security policies and programmes. There must be equitable participation of women in decision-making and policy-making.

Feminism has brought a greater depth of understanding about gender. One important contribution is the concept of intersectionality: Gender roles cannot be seen in isolation. Gender intersects and is intertwined with other factors such as race, class and ethnicity that affect or even determine the condition of men and women, their opportunities and choices.

Gender analysis has sometimes had the unintended effect of marginalising women in development programmes. Once women’s specific roles and tasks were identified, projects were devised to direct resources and assistance to women. Unfortunately, in most cases, these resources were miniscule and women ended up being isolated in small income generating projects, tacked onto larger development programmes. There is no doubt that many of these small-scale projects have provided much needed help to women in their tasks of providing food for their families. However, in comparison to overall development aid and assistance, resources allotted to women have been small.

Gender mainstreaming by development agencies is the attempt to counter the marginalisation of women in small projects and bring them into the mainstream of development projects and programmes. On the surface, this may seem like a good idea, but in practice, it is more complex and may have negative effects on women.

Gender mainstreaming can be critiqued from a feminist point of view when it overlooks the importance of first empowering women to participate in decision-making and policy-making. While structures, legislation and attitudes can be changed to enable women’s participation, women’s empowerment comes from themselves. For this to happen, women need to organise themselves as women to raise their awareness, build solidarity and mobilise. This has always been true of marginalised or oppressed groups, whether workers, indigenous peoples or ethnic minorities. It is also true of women.

Feminists also strongly critique the notion of mainstreaming women into a patriarchal model of development. We do not want to integrate or mainstream women into patriarchal systems. Uncritical mainstreaming of women could mean drowning women in the “male stream.” Only if we can enter the mainstream in sufficient numbers and with sufficient strength and ability to challenge and change the mainstream, does it make sense to mainstream women.

As feminist scholar Vandana Shiva pointed out, “Gender analysis...needs to take into account the patriarchal bias of paradigms or models, processes, policies and projects of global economic structures. It needs to take into account how women’s concerns, priorities and perceptions are excluded in defining the economy, and excluded from how economic problems and solutions are proposed and interpreted.”

Mainstream Obstacles to Food Security

Misguided mainstream economic models and development policies have led to the present food crisis. Unfortunately, most proposals that tackle the crisis only promise more of the same. These are obstacles, not solutions.

Development policies continue to promote large-scale commercial agriculture to the detriment of small food producers. Agriculture and agricultural trade are increasingly dominated by large agroindustrial corporations that control crop, livestock and fishery production, food processing and marketing as well as seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, and farm and fishery equipment. Transnational companies are also taking over millions of hectares of land in developing countries for the purpose of converting them to monoculture of industrial biofuels. As a consequence, millions of peasants and small farmers, especially women food producers, are losing the ability to produce and provide food for themselves and their households.

In spite of some very positive efforts, development agencies as a whole have failed to bring substantial representation of peasants, farmers, fisherfolk, and indigenous people into discussions on how to address the problems of the food crisis. Above all, the voices of women food producers and food providers are missing.

Climate change is speeding up environmental degradation and loss of natural resources caused by the intensification and industrialisation of agriculture, destruction of forests for commercial purposes, over-exploitation of fisheries, the loss of biodiversity due to monoculture cropping and the decreasing varieties of seeds. As the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction(UN-ISDR) stated: “Climate change is expected to increase the severity and frequency of weather-related hazards such as storms, high rainfalls, floods, droughts, landslides, water stress and heatwaves. Together with sea level rise caused by global warming, such phenomena will lead to more disasters in the future – unless prompt action is taken.”

Brazil: Peasant women struggling for food sovereignty against agribusiness

On 4 March 2008, around 900 women of Via Campesina Rio Grande do Sul occupied the 2,100 hectares “Fazenda Tarumã” in Rosário do Sul, Brazil. The women cut the eucalyptus and planted native trees in a land illegally purchased by the giant Finish-Swedish paper and celluloses company Stora Enso. The police violently attacked the peaceful gathering, injuring badly as many as 50 women.

This action was one of the activities organised for the International Women Day on the 8th of March. Women farmers are the most affected by the current export-oriented agriculture model based on the plundering of natural resources and the exclusion of small farmers by transnational companies. All around the world, eucalyptus plantations as well as other monoculture plantations (green deserts) destroy the environment and prevent small farmers from making a living and producing food for all.

From Via Campesina

Gender dimensions of continuing food insecurity

Despite the two decades of gender analysis, a great accumulation of data and information on women’s roles in agricultural production and food security and the establishment of gender units within development agencies, there is still a bias toward men. Women’s needs, perspectives and knowledge are not given sufficient consideration by development agencies in policies, programmes and projects – or by NGOs and other organisations. This, despite the progress of women in empowering themselves and making their voices heard more and more in their communities as well as organisations of farmers, peasants, fisherfolk and indigenous peoples.

Women also represent an immense source of potential and power to combat the increased disaster risks that climate change will bring. Women in developing countries are already on the front line of adapting to climate change, with increasing floods and droughts impacting upon their livelihoods.

The promotion of large-scale commercial farming for export is detrimental to smallscale food production for household consumption. Women are particularly affected as they tend to make up the great majority of small-scale food producers in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia.

Lack of land rights and access to resources is a major obstacle. Discriminatory legislation in many countries limits women’s access to land, credit and membership in agricultural cooperatives. Even where legislation does not limit women’s rights to land titles and membership in cooperatives, tradition may do so. Similarly, women have benefited little from agrarian reform programmes which are often restricted to men or male heads of households. This usually means that women also have less access to agricultural inputs, extension services and training which are still mainly directed to men.

Agricultural research focuses mainly on cash crops that men grow while the food crops that women grow are neglected. And yet the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) maintained, women farmers can be experts in their own domain. It cited the productive results of the collaboration among local women farmers with scientists from the Rwandan Agricultural Research Institute (ISAR) and Colombia’s International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in an attempt to breed improved bean varieties. IFPRI reported, “the selections of the women farmers substantially outperformed the selections of the bean breeders. Similar results have come from India and the Philippines, demonstrating that a vast reservoir of expert human capital remains largely untapped: few women are agricultural extension agents, and agricultural research and extension institutions rarely seek the expertise of local women farmers.”

Climate change, environmental degradation and the loss of natural resources increases the work load of women who have to walk farther to collect fuel wood and water. As a result of deforestation, women have also lost the source of many food items, medicinal products and other products used in the household.

According to the UN-ISDR: “It is a wellknown prediction that women in the developing world will suffer the most from the effects of climate change. What needs equal emphasis, however, is the fact that women also represent an immense source of potential and power to combat the increased disaster risks that climate change will bring. Women in developing countries are already on the front line of adapting to climate change, with increasing floods and droughts impacting upon their livelihoods. As pivotal managers of natural and environmental resources and key frontline implementers of development, women have the experience and knowledge to build the resilience of their communities to the intensifying natural hazards to come.”

In conflict and disaster situations, women and children often suffer more severely because of discrimination that hinders their access to resources. Worse, violence against women and children in these areas has escalated tremendously. Targeting emergency distribution of food aid directly to women can help as women are the ones responsible for providing food to their children and other household members, and are those most likely to distribute food aid to family members. However, measures must be taken to ensure that women do not become victims of violence and human rights abuses in situations where emergency food aid is distributed (WFP, 2009).

What must be done to ensure food security

Small holder agriculture must be promoted, including crops and livestock and artisanal fisheries. Farmers, peasants, fisherfolk and their organisations have been saying this for years, along with supportive NGOs and CSOs. In the face of the global food crisis, international development agencies are also re-looking at small holder agriculture as a way out of the crisis. FAO remarked, “focus should be on helping producers, especially smallscale farmers, to boost food production….” Women food producers must be central to this focus because they comprise a large proportion of small-scale and subsistence farmers and play multiple essential roles in food security.

Meanwhile, women food producers must be empowered and enabled to speak. They must be listened to and heard at the community level, within peasant, farmer, fisherfolk and indigenous organisations and at the tables of government and development agencies at all levels. They must be empowered to participate in debates, discussions and decision-making.

Organising and mobilisation of women are key to empowering women’s participation in decision-making in regard to food security policy and programmes. Rural organisations have the potential to promote food security, strengthen women as food producers and empower women to participate in policy and decision-making on food security. Many of these organisations are themselves maledominated, particularly at the decisionmaking level. This is gradually changing along with a growing gender awareness and as women are becoming more active. This may enable these organisations to play a more effective role for the benefit of both men and women.

This is a change from the situation at the time of the WFS and parallel NGO Forum on Food Security in 1996. At that time, not only were there no women farmers represented at the government Summit, but very few women farmers were able to participate in the NGO Forum. A significant exception was a group of women farmers, peasants and indigenous women food producers from every region of the world who gathered in a Rural Women’s Workshop before the Summit and the NGO Forum to strategise and present their views at the Forum. This workshop was organised by Isis International, Via Campesina and the People Centred Development Forum.

These women deplored their exclusion from the process of food policy deliberation and formulation and declared that “food is a fundamental human right.” These women drew up a statement for action and strategies for an alternative policy to ensure food security. Now that the failure of mainstream food security policies has brought about a global food crisis, it is time to re-examine the wisdom of these peasant, farmer and indigenous women and consider their proposed strategies:

The democratisation of the access to resources, especially land, water, seeds and intellectual property.

- Promotion of sustainable agriculture and community-based resource management.

- Establishment of local, people-based trade systems and infrastructure.

- Empowerment of women through equal representation in decision-making bodies at local, regional, national and global levels.

- Access to education for women and girls.

- Access to credit and other financial support for women.

- Appropriate education, health, recreation, child care and other infrastructure support systems designed by and for rural communities with consideration for all genders.

Empowering and Creative Solutions

Women are rising to the challenges of food insecurity and the food crisis. They are intensifying creative and empowering efforts and actions. These initiatives, small though many of them may be, are not only helping women and their families to survive and cope with the food crisis. They are part of a growing movement and consciousness in which women and communities are not waiting for top down solutions, but coming up with their own.

References

Alordo, Rocio. (2008). Saving the roots of biodiversity. Lima: Latin America Press.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2008). State of food insecurity in the world 2008. Rome.

FAO, World Bank and International Fund for Agricultural Development. (2009). Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook. Rome.

FAO/NGO Regional Consultation for Asia and the Pacific on the World Food Summit, Bangkok, Thailand, 29-30 April 1996. Report.

International Baby Foods Action Network (IBFAN),

International Food Policy Research Institute. (1995). “Women as Producers, Gatekeepers, and Shock Absorbers.” in 2020 Vision Brief (17).

International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty

International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR). (2008). Gender perspectives: integrating disaster risk reduction into climate change adaptation good practices and lessons learned.

Learner, Michele.(2006). “Budgeting for Justice.”

Shiva, Vandana. (1995). Trading our lives away: an ecological and gender analysis of ‘free trade’ and the WTO. New Delhi: Research Foundation for Science.

Smith, Alex Duval. (22 February 2009). “Defiant Mugabe’s birthday banquet.”

World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA)

World Food Programmes. (2009). Gender policy: Promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women in addressing food and nutrition challenges. Rome.

Very ow food insecurity (described as “food insecurity with hunger” prior to 2006) means that, at times during the year, the food intake of household members was reduced and their normal eating patterns were disrupted because the household lacked money and other resources for food.

This means that people were hungry, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “the uneasy or painful sensation caused by want of food,” for days each year.

Although hunger in the US is less dire than in developing nations, it is nonetheless quite serious. Starvation is rare here, but malnourishment is not.

According to the Food Research and Action Center, 36.2 million people lived in households considered to be food insecure in 2007. Of these 36.2 million:

- 23.8 million are adults (10.6% of all adults) and 12.4 million are children (16.9% of all children).

- The number of people in the worstoff households increased to 11.9 million from 10.8 in 2005. This is consistent with other studies and the Census Bureau poverty data, which show worsening conditions for the poorest Americans.

- Black (22.2%) and Hispanic (20.1%) households experienced food insecurity at far higher rates than the national average. These are households headed by a single woman or have incomes below the official poverty line. The food insecurity rate for families with children is double that for adults—15.8 per cent compared to 8.7 per cent

Use of Emergency Food Assistance and Federal Food Assistance Programmes

There are federal and state programmes that work with families who are poor and food insecure. In 2007, 53.9 per cent of food insecure households received help from at least one of the three major federal food programmes, which are implemented by the USDA — Food Stamps, the National School Lunch Programme and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Programme for Women, Infants and Children.

- 49 per cent of food stamp recipients are children.

- 51 per cent of client households with children under the age of three participated in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

- During the 2007 federal fiscal year, 17.9 million or 62 per cent of all client households with children under the age of 18 participated in a school lunch programme, but only 13 per cent— just under 2 million—participated in a summer feeding programme that provides free food when school is out.

Spending for government nutrition programmes has for decades lagged far behind the need. Meanwhile, Congress generally responds to increased demand by tightening the eligibility for assistance.

Food banks are a treasured source of aid for millions of needy Americans, but they increasingly face shortfalls in supplies and their ability to help. Nationally, donations are up about 18 per cent but demand has grown to 25 to 40 per cent. As fuel costs increase, food stores stock fewer inventories to reduce shipping costs, thus making them less available to contribute to food banks. Food producers are also cutting inventory with like results while government surplus programmes make far less food available than they did in years past.

Sadly, this results in the nation’s food banks having less resource in carrying on their charitable work of combating hunger, even as the demand for their help increases. Feeding America, formerly America’s Second Harvest, has a network of 206 food banks. About 70 per cent of new clients are making their first visit to a food bank and many are working at jobs:

- Among members of Feeding America, 65 per cent of pantries, 61 per cent of kitchens, and 52 per cent of shelters reported that there had been an increase since 2001 in the number of clients who come to their emergency food programme sites.

- More than nine million children are estimated to be served by Feeding America. Over 2 million of them are children under five. These more than nine million children represent nearly 13 per cent of all children under age 18 in the US and over 72 per cent of them live in poverty.

- 3.4 per cent of all US households (3.9 million households) accessed emergency food from a food pantry one or more times in 2007.

- In the same year, food insecure households were 17 times more likely than food secure households to have obtained food from a food pantry.

- Food insecure households were 19 times more likely than food-secure households to have eaten a meal at an emergency kitchen in 2007.

- Feeding America provides emergency food assistance to an estimated 25 million low-income people annually, an eight per cent increase from 23 million since Hunger In America 2001.

- Feeding America provides emergency food assistance to approximately 4.5 million different people in any given week.

While work on the Farm Bill is finished, there are other legislative opportunities for addressing hunger, primarily in the US. Child Nutrition Programmes, including the school breakfast and lunch programmes and programmes for women, infants and children will expire soon and must be reauthorised in 2009.

NGO Response to Hunger

Many non-profit organisations are working together to make sure that there are new programmes that address the issue of hunger as well as adequate funding in order to carry out those programmes.

It has been proven that children and low income families are not getting the nutrition that leads to a healthy lifestyle. Many foods that are consumed are high in sodium and high-fructose corn syrup, causing high blood pressure and obesity.

In all of this dire news of hunger and malnutrition, there are a number of bright spots where community-based organisations are creating programmes and activities that help eliminate hunger. Many of these organisations operate under these principles:

- Community food security includes a comprehensive strategy to address many of the ills affecting our society and environment due to an unsustainable and unjust food system.

- Community focus A community-foodsecurity approach builds the community’s food resources to meet the community’s own needs. Resources may include supermarkets, farmers’ markets, gardens, transportation, communitybased food-processing ventures and urban farms.

- Self-reliance and empowerment Community food security projects build the abilities of people to provide for their food needs. Community food security builds upon community and individual assets instead of focusing on deficiencies. Community-food-security approaches engage community residents in all phases of project planning, implementation and evaluation.

- Local agriculture Stable local agricultural is the key to a communityresponsive food system. Farmers need more access to markets that pay them a decent price for the results of their labour. And farmland needs land-use planning to protect it from suburban development. By building stronger ties between farmers and consumers, consumers gain a greater knowledge of and appreciation for their food source.

- Systems-oriented Community food security programmes are typically inter-disciplinary. They cross many boundaries and incorporate collaborations with multiple organisations.

There are over 70 million gardeners in the US and about 25 million people who are chronically hungry, including 9.9 million children.

Plant a Row for the Hungry encourages gardeners to plant an extra row, and donate the produce to local food banks and community service agencies. There is no organisation that oversees this programme but it has taken hold in the US where people are growing food to feed their communities.

In Wisconsin, the Kane Street Community Garden, a part of the Hunger Task Force of La Crosse, aims to eliminate hunger within and by the community. Volunteers plant and harvest the many crops that grow in the nearly two-acre garden. What is not handed out to the public and volunteers are added to the Food Recovery Programme, which goes out to any of the 42 agencies served by the Hunger Task Force.

Also in Wisconsin is Growing Power, a national non-profit organisation and land trust that supports people from diverse backgrounds and the environments where they live by helping to provide equal access to healthy, high-quality, safe and affordable food for people in all communities.

Growing Power implements this mission by providing hands-on training, on-the-ground demonstration, outreach and technical assistance through the development of community food systems that help people grow, process, market and distribute food in a sustainable manner.

Growing Power is a global model for sustainable community food systems, having done outreach trainings in Macedonia, Ukraine, Tennessee, London, Arkansas and other places. Their Farm-City Market Basket (FCMB) Programme is a year-round food security programme that supplies safe, healthy and affordable vegetables and fruit to communities at a low cost. FCMB provides a market for small farmers to sell their food while feeding communities in “food deserts” affordable healthy food.

US Farm Bill

The Farm Bill is a compherensive legislation on agriculture in the United States. Annually reviewed and ratified, the bill sets the the government’s subsidies to farmers, especially agri-businesses among others. Despite the inconsistency of these subsidies with the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the threat of a veto from then US President George W. Bush, the strong lobbying in Congress managed to reinstate these subsidies.

As US Department of Agriculture Secretary Edward Shafer said, “Today, the United States House and Senate announced the completion of a farm bill that unfortunately fails to include much needed reform and increases spending by nearly $20 billion.”

Estimated to cost the government US$289 billion in the next five years, the Farm Bill of 2008 earmarked US$200 billion for domestic food aid; US$43 billion for subsidies for rice, cotton, corn, soybeans, wheat and other crops; US$27 billion for conservation programmes; and US$23 billion for crop insurance.

Sources: Khor, Martin. (19 May 2008). “New US farm bill will anger the world.” ; Ryan, Missy. (12 May 2008). “U.S. farm bill could run afoul of global trade rules.” ; The Farm Bill of 2008 webpage of the USDA

In New York, Rochester Roots develops selfreliance by providing the education and tools that help low-income people obtain nutritious and locally grown food through the development and marketing of urban produce and products. They strive to achieve this vision through their participation in the local food system and through education and advocacy.

Sharing the Harvest is a programme in which produce is distributed to participating lowincome youth and neighbouring residents so that they feed their families, or for educational purposes in the classroom.

Through their South Wedge Farmers Market, Rochester Roots engages in entrepreneurial activities with vendors, youth and seniors. Rochester Roots also teaches the community how to cook produce into nutritious meals in their Community Kitchen Cooking Class programme and offers teenagers the opportunity to intern with local chefs.

Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Rescue Mission Inc. (BRM) is a community-based organisation in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York that develops creative solutions to food justice, community health and the economic challenges their community endures on a daily basis. Its programmes include the Bed- Stuy Farm, the Neighbourhood Farming Institute, the Food Outreach Programmes and the Malcolm X Boulevard Community Farmers Market.

In 2007, the Bed-Stuy Farm yielded 7,000 pounds of fresh organic produce, which was distributed to families at risk of hunger through BRM’s emergency food programmes. Community education programmes are held at the Farm. These include topics such as nutrition and urban agriculture, entrepreneurship and leadership skills.

Their Neighborhood Farming Institute is a classroom and community center focused on the Farm while the Food Outreach programme provides weekly food pantry services. BRM also runs the Malcolm X Boulevard Community Farmers Market.

Food Not Bombs

Food Not Bombs is a movement that promotes the distribution of food and other resources over other spending priorities such as warfare. Formed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States by antinuclear activists in 1980, Food Not Bombs has been growing, expanding its advocacies as well as bases. While serving communities especially during disasters and tragedies such as September 11 events, the Asian tsunami, Hurricane Katrina and also protesters during rallies, Food Not Bombs has also been opposing neoliberal capitalism which has resulted in the current food and financial crises.

The recent International Labour Organisation (ILO) reports on the global and regional employment trends paint a stark picture of rapidly increasing unemployment in 2008 as a result of the global economic crisis. The situation is expected to worsen in 2009 with more massive job losses. Low income workers and the poor are already paying heavily for the economic crisis, with women being the hardest hit.

Global unemployment rates increased from 5.7 per cent in 2007 to six percent in 2008 of some 10.7 million people – the highest year on year increase since 1998. Unemployment rate for women is higher with 6.3 per cent compared to 5.8 per cent for men. Young people constitute much of the unemployed, with fewer work opportunities.

Work Scenes for 2009

The ILO presents several worrying scenarios this year. A more “realistic” scenario will see unemployment increase by 30 million people. A “worst case” scenario—which given recent trends in decline in growth rates and job losses, is probably the more likely scenario— sees global unemployment increase with 51 million unemployed people.1

Under the “realistic” scenario, the number of unemployed in Asia would increase by 5.1 per cent to 7.2 million. But even in the most optimistic scenario, the number of unemployed women would rise to 4.4 per cent, compared with 3.8 per cent for men. Meanwhile, under the “pessimistic” scenario, the number of unemployed in the Asian region could spiral up by 23.3 million. A drastic and staggering increase of those in extreme and working poverty to 140 million is projected in 2009.

Youth are also likely to be disproportionately affected by the crisis. Already in 2008, youth in Asia were more than three times as likely as adults to be unemployed. In Southeast Asia, youth unemployment rate stood at 15 per cent in 2008. This figure could rise sharply, as young workers are likely to be among the first to be sacked, while first-time jobseekers are likely to find themselves at a substantial disadvantage when competing against a rising pool of more experienced and recently unemployed jobseekers.

Last year, some 250,000 workers in plant and machine operation and assembly were sacked in the Philippines while over 40,000 were laid off in Indonesia in the last two months of 2008. In China, tens of millions of workers have lost their jobs and some 20 million migrant workers have returned to their homes in the rural areas, thus causing massive pressure on the rural economies. Meanwhile, some 300,000 additional workers in the formal sector could lose their jobs in Vietnam in 2009.

Reenacting the 1997’s Impact on Women

An analysis of seven industry groups most affected by the crisis to-date2—based on Labour Force Surveys of Thailand and the Philippines, and the 2004 Living Standards Measurement Survey of Vietnam—shows that the impact of the job losses follows gender lines. Women dominate garments, textiles and electronics at the ratio of 2 to 5 female workers for every male worker and are thus experiencing some of the initial blows of job losses.3

These job losses represent a massive attack on the living standards of low-income women, who mostly gained some level of regular employment with the partial industrialisation of the 1980s and 1990s. Any remaining gains made in the standard of living of the working population in this period are now being wiped out.

Based on early 2009 trends, growth in the Asian region is now expected to fall to its lowest level since the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

- Current forecasts indicate that economic growth in the Asian region will drop to 2.3 per cent in 2009, with 2.7 per cent growth projected in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines, compared to a forecast of 4.2 per cent in November last year.

- In China, the government’s target for growth in 2009 is eight per cent, but the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects growth to decline to 6.5 per cent.

- In India, current government estimates are 6.5 to 7.5 per cent, but IMF projections are a fall of growth to 5.1 per cent.

- Indonesian officials expect a further deceleration in 2009 to between 4.5 and 5 per cent.

- In Korea, some analysts project negative growth for 2009.

- In the Philippines, growth is expected to fall as low as 2.2 per cent from 7.2 per cent in 2007.

- Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry now expects growth to fall to between negative 5 and 2 per cent.4

This follows the experience of the 1997 Asian crisis. In the Philippines, unemployment rose to 12 per cent for men and 15 per cent for women in 1999.5 After the crisis, the decline in labour force participation rates for women of all ages exceeded those for prime- age men, except in Indonesia. The decline in hours worked by women were greater than that by men in the formal sector, with hours by men declining by 1.4 per week and by women, 2.9 per week. At the other extreme, the incidence of long hours for women increased, rising from 20 per cent in 1994 to 24.9 per cent in 1998. For men, it fell following the crisis.6

There were also significant erosions in real wages in countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea. In Thailand, real wages declined particularly for women in urban areas.7 There was also a drastic drop in incomes in the informal sector which is almost exclusively the preserve of women (Sing, Zammit, 2000)8.

Young workers, including young women workers, are especially vulnerable during an economic crisis due to their lack of experience, slowdown in hiring and seniority practices. Youth unemployment rose to very high levels during the Asian crisis. In 1998, young male unemployment rates ranged from 11.2 per cent in Thailand to 20.8 per cent in South Korea, with female youth unemployment ranging from 8.6 per cent in Thailand to 22.1 per cent in the Philippines.9

Recent migrant workers are also likely to lose their jobs. There is evidence from the Asian crisis that a majority of South East Asian region’s migrant workers expelled from some of the crisis countries were women (Singh, Zammit 2000).10 With the feminisation of overseas migration, women migrants who tend to predominate in unregulated domestic, entertainment and agriculture jobs are more likely to lose their jobs and be increasingly vulnerable to working in exploitative conditions.

Many Asian economies rely on remittances from overseas workers, as well as rural to urban migrant workers. In countries such as the Philippines, the world’s fourth largest recipient of remittances after China, India and Mexico, the growth of remittances from overseas Filipino workers is predicted to slow down to as low as six to nine per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), compared to 10 to 14 per cent of GDP in 2008.11

High food prices can have a disproportionate impact on women’s nutritional status. Cutbacks of food consumption in the household due to high food prices and food insecurity are first borne by women and girls.

Women at the crux of the crisis

With the crisis, women work harder inside and outside the home to make up for reduced incomes, inadequate social protection and government cutbacks in social services. This results in increasing time pressure on women in “making ends meet.”

During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, women also took on extra income generating activities to make ends meet. In the Philippines, both male and female unemployment rates rose between 1997 and 1998. However, the mean weekly work hours for those employed moved in opposite directions for men and women, with those falling for men and rising for women.

Among the factors that may explain an increase for women is an increase in the hours of work undertaken by home-based women working on subcontract. In the Philippines, findings show that subcontracted home-based women workers took on second and even third jobs in the informal labour market during the crisis (Lim, 2000). This increase in average hours that women spend in paid work is in a context where women spent almost 8 hours a day on housekeeping and childcare, compared to 2.5 hours for men.12

Resource-strapped families also end up pulling children out of school, resulting in an increase in child labour. Girl’s education tends to suffer, with long-term negative implications for women’s income-earning power, reproductive health and even the well-being of future generations.

High food prices can have a disproportionate impact on women’s nutritional status. Cutbacks of food consumption in the household due to high food prices and food insecurity are first borne by women and girls.

According to an Oxfam research on food price increases in Cambodia, mothers and elder sisters eat less than the other members in the 21 per cent of researched households. In the worse cases, eight per cent of mothers and elder sisters skip meals so that other household members have enough to eat (CDRI, 2008).

With food price increases and reduced household income as a consequence of the economic slowdown, staples tend to consume more of the household food expenditure, resulting in a reduction of micro-nutrients which are present in vegetables, meat, fish and other sources and which are needed particularly by girls and women. Pregnant and lactating mothers are often considered the most at risk due to the poor nutrition.

Studies also show that stress and conflict within households become commonplace as a result of diminishing resources, increasing incidents of domestic violence and women’s involvement in prostitution.

Of Imperatives and Alternatives

Women must not bear the burden of the crisis. It is essential that spending on social protection systems and social services is maintained and even increased when economic shocks strike. Public provision of basic social services ameliorates the impact of gender inequality within households while cutbacks in these services affect women and girls disproportionately.13

Nevertheless, except in Malaysia, education and health budgets were severely cut in countries affected by the crisis of 1997 just when the need was the greatest. In 1998, for example, Thailand’s public health budget shrank by nine per cent and education budget fell six per cent.14 Some of the current fiscal margins have already been used up by governments as they were forced to respond to the food price crisis through emergency assistance and increased safety nets, thus putting more pressure on budgets for social protection and essential social services such as health and education.

The Asian financial crisis and the 2008 food price crisis also exposed the inadequacy of existing social protection systems and the need to strengthen them and address their inherent gender biases. While improvements have been made since the 1997 crisis, critical gender gaps continue to persist.

A majority of wage support policies such as severance pay and unemployment insurance are still biased in favour of prime- age male workers. In China, Vietnam and Thailand, women are often not covered by their husbands’ pension funds.

In general, women are disadvantaged by social protection systems that are linked to labour market status as they are concentrated in non-standard conditions of employment, lower-wage employment, and the informal economy.15

Social protection systems should be designed not only to mitigate and protect, but also to promote the livelihoods. They could have a greater impact if they incorporate women’s needs as workers and mothers.

In developing countries, a majority of the poor, including poor women, obtain security through infor mal mechanisms. These informal mechanisms include community and social networks and patronage. But even in these informal systems of social security, there is an inherent gender bias, with the burden falling disproportionately on women due to their role as primary carers in the home.

Any economic stimulus package must start with job protection with an immediate moratorium on lay-offs, and genuine job creation in order to stimulate national consumption and economic recover y. Restructuring the economy by breaking from export-dependent neoliberal policies is crucial. Other important measures include:

- In nationalising banks and financial institutions, governments must ensure that the funds are used not for profits but for social development that creates jobs. The nationalisation of banks, instead of their continued privatisation, is the only step forward to prevent the collapse of the banking system and the entire economy.

- The banks’ books must be opened. Bank oversight must be strengthened as must the mechanisms of strict regulation. This, to make the national banking systems transparent for they are public service institutions carrying the populations’ savings.

- Massive increase in budgetary allocations for social spending. Priorities are employment security, a living wage, public health and education, and housing.

- The repudiation of public debt and an immediate moratorium on debt payment.

- Withdrawal of onerous taxes such as consumption taxes on the poor and vulnerable.

- The shifting of the military budgets and war expenditures towards productive endeavour and job creation.

- For migrants, the immediate creation of a social fund that covers their smooth reintegration, decent local employment and livelihood and substantial welfare projects.

- For farmers and agricultural workers, the implementation of genuine agrarian reforms that include a land-to-the tillers programme, access to agricultural credit and assistance, job security and market access.

- Policies that guarantee women’s access to and control over resources, including land and titling rights.

- Payment for women’s unpaid labour in the home, as introduced in the Venezuelan constitution.

- The introduction of gender budgeting in economic policy making, covering the budgets of all line ministries, to ensure that women benefit from all economic policy measures.

- Participatory budgeting to enable civil society and women’s organisations to participate in the budget process such that government processes become more transparent, accountable and receptive to the needs of women and the poor.

- The discourse on new financial architectures must take into account gender equity considerations, such that the development of new institutions with new responsibilities are based on a framework of enabling gender equity, providing spaces which are accessible from the kitchen for public dialogues on priorities and alternatives which address the needs of poor women and men.

Footnotes

1 ILO, Global Employment Trends, January 2009.

2 Identified by the ILO as: garment textiles, garments, footwear & leather products, electronics (plus electrical and telecommunications products), car manufacturing and auto-parts, hotels and restaurants (key parts of tourism), and construction.

3 ILO Technical Note, Asia in the Global Economic Crisis: Impacts and Responses from a Gender Perspective, February 2009.

4 ILO, The fallout in Asia: Assessing labour market impacts and national policy responses to the global financial crisis, February 2009.

5 www.unifem-eaeasia.org/Resources/GlobalEconomy/Section4.html

6 ILO, WB 2001, pp 391

7 http://www.unescap.org/dr pad/publication/protecting%20marginalized%20groups/ch1.pdf

8 Singh, Zammit, pp 1261

9 Ibid pp 17

10 Singh, Zammit, pp 1261

11 ADB draft working paper on the Global Economic Slowdown and the Impact on Poverty and Non-Income MDGs, January, 2009.

12 Elson, D, A View from the Kitchen, 2002, pp 8

13 Pp 18

14 ADB draft working paper on the Global Economic Slowdown and the Impact on Poverty and Non-Income MDGs, January, 2009.

15 ILO Technical Note, Asia in the Global Economic Crisis: Impacts and Responses from a Gender Perspective, February 2009.

Page 1 of 3

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.