More Under the Veil: Women and Muslim Fundamentalism in MENA

It is important to begin any discussion related to religious fundamentalism with an exploration of what is meant by the term “fundamentalism.” The word “fundamentalism” was originally coined in reference to a movement within the Protestant community of the United States in the early part of the 20th century. In the broadest sense, fundamentalism can be understood as “a selective retrieval and imposition of...[religious] law and sacred texts as the basis for a modern socio-political order” (Hardacre 1994:130).

Source: Amnesty International (25 November 2009). “Yemeni women face violence and discrimination.”

In photo is the city of Sanaa from Wikimedia Commons

But religious fundamentalism is not a monolithic entity. Around the world, there is a wide range of fundamentalisms and fundamentalist movements that display a number of similarities – most notably their interpretation of the family, gender roles and interpersonal relations – but in no way share identical plans. Generally speaking, the ideologies of fundamentalisms have translated into movements that show little respect for the principles of human rights and have little tolerance for people of other faiths. They are often anti-women (Rouhana, 2005).

The issue of women – their status, rights, roles and responsibilities, both within the family and the community – is one of the main focuses of fundamentalist discourses.

For quite some time, women from Middle East and North Africa have been the subject of concern. Yet there is much more to be explored about their methods of resistance.

Women are seen as the bearers of cultural authenticity (Kandiyoti,1993) and their complicity within the religious framework is necessary to its survival. As Gita Sahgal and Nira Yuval-Davis in Refusing Holy Orders pointed out, “(t)o conform to the strict confines of womanhood within the fundamentalist religious code is a precondition for maintaining and reproducing the fundamentalist version of society.”

For quite some time, women from the Middle East and North Africa have been the subject of concern and the rallying point of feminist advocacies and campaigns whose language has been coopted by right-wing fundamentalist regimes in the West on many occasions. Yet there is much to be teased out the deprivation and violence these women experience and much more to be explored about their methods of resistance.

Muslim Fundamentalism in MENA

The rise of Muslim fundamentalisms since the 1970s should be viewed through the trends towards modernisation and perceived threats of neocolonialism. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, which is characterised by the rapid spread of globalisation, newly-formed nation-states attempted to hastily develop and compete in a globalised world.

In many regions, this often translated into the adoption of neoliberal economic policies and the further inclusion of women in the public sphere. Women had already begun to take a more active public role through anti-colonial and independence movements.

New nation states indeed emerged in the 1950s, many of them formally severing their links to various empires. There are obvious exceptions to this trend though such as Palestine as it is still in the throes of its struggle for independence and Iran which was never a formal colony.

This resurgence could be partly viewed as a backlash against the failure of secularised states to effectively develop and maintain “cultural” integrity – the issue of women’s sudden inclusion in public spaces being at the forefront. It was a period of great upheaval in reaction to social failures such as the non-provision of basic social services, rampant corruption and the growing gap between rich and poor, among others.

The dissatisfaction in the Muslim Middle East was further bolstered by the Arab states’ defeat by Israel in the 1967 war and the Western powers’ support for Israel, which was perceived as an outright attack on Islam and Arab “cultural authenticity” and an entrenchment of neocolonialism. All of these forces culminated in the coming of the 1979 Iranian Revolution which led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the first and only Islamic state in the region. But these factors have strengthened the resolve of Muslim fundamentalist movements across the entire region and have shaped the essential elements of Muslim fundamentalisms in the Middle East today.

Battle for the Hijab

Battle for the Hijab

In 2008, people gathered on the streets of Ankara to protest the decade long ban on the hijab or the head covering in public places and univeristies. While the government saw it as an aid to women who would like to participate more in public life, the ban has discouraged many women to study. The hijab, which covers the head up to the nape and the niqab, which covers the whole body save for a slit for the eyes, have been donned by Muslim women in the name of modesty. Islamic scholars remain torn though in interpreting the use of the hijab in moden times. But Open Democracy’s Fred Halliday put it nicely, “There is only one consistent, universalist and secular position on the wearing of religious headwear - for Muslims, Catholic nuns, or Orthodox Jewish haredim alike: to be against it, but to defend the right to wear it.”

Sources: Al Jazeera (6 June 2008). “Turkey’s AKP discusses hijab ruling.” ; Asser, Martin (5 October 2006). “Why Muslim women wear the veil.” and Halliday, Fred (16 December 2004). “Turkey and the hypocrisies of Europe”

Photos from Story og a Muslimah and the Lebanese Development Network

Muslim Fundamentalisms and Women

While women’s attire in Muslim contexts, the hijab – chador, burka, abiya – always receives ample attention from Western news sources, it is far from being the most important issue that women face in their confrontation with Muslim fundamentalisms.

In reality, it is the Shari’a–derived personal status laws governing women and the family where the influence of fundamentalisms is felt most acutely. Personal status laws govern marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance (Ziai,1997). In essence, personal status laws outline what women’s rights are and what they are allowed to do within the confines of the dominant interpretation of Islam in each specific country. Whether it be “Islamisation from above” or “Islamisation from below,” these are the most contentious laws around which both Islamists and women mobilise (Legrain,1994).

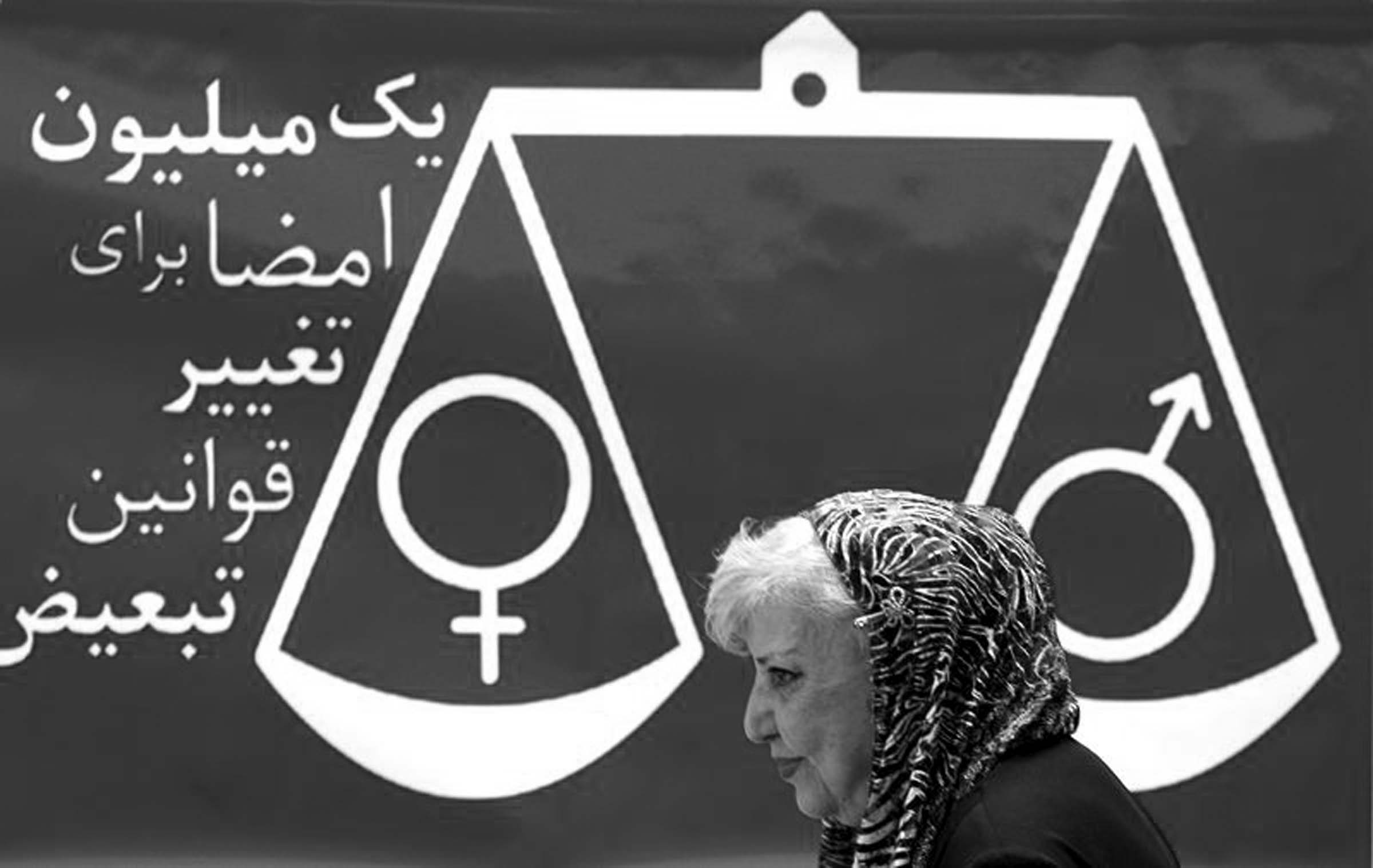

Although women in these contexts are sometimes represented as passive victims of fundamentalists’ projects, this is far from being the case. As previously noted, women were active participants in the struggle against colonialist and neocolonialist impositions and even up to the present with the continuing fight for Palestinian statehood. Moreover, women, including those observing the hijab, have actively mobilised around the perceived injustices enshrined in personal status laws. The One Million Signatures Campaign in Morocco in 1992, the One Million Signatures Campaign in Iran since 2006 and the protest movement in Iraq against the abolition of Iraq’s progressive personal status laws in 2003 are only a few examples of women-led mobilisations. These courageous women often expose themselves to reactionary criticism and risk being targeted as “puppets” in the neocolonial project.

Unlike bygone colonial times, when the enemy was defined quite clearly as the foreign occupier, during the current times of neo-colonialism and ongoing imperialism, “the other” can be found in the midst of the national fabric. And, the “other within” generally turns out to be the westernised middle classes, the nouveau riche, the religious and ethnic minorities, and . . . the human rights activist trying to uncover his or her government’s atrocious human rights record. But the “real favourites” when it comes to identifying “traitors” and “infiltrators”; are those “appalling women” who dare to defy tradition and struggle for their legal rights and greater equality. (Al-Ali, 2001:5)

The concepts of women’s rights as human rights and feminism are presented by these reactionary forces as a Western import in contradiction to “authentic” Muslim culture. These forces oppose proliferation of women’s rights movements and foreignfunded non-governmental organisations (NGOs), coupled with the new rhetoric propagated by the international community of women’s rights for democracy – as if democracy is inherent only to Western culture. But as Aili Mari Tripp in Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organizing, and Human Rights pointed out, “Regardless of the common perception in the West that ideas regarding the emancipation of women have spread from the West outward into other parts of the world. In fact, the influences have always been multidirectional, and that the current consensus is a product of parallel feminist movements globally that have learned from one another but have often had quite independent trajectories and sources of movement.”

Photo from Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty.

Furthermore, various feminisms have developed in the South. But even though there is ample evidence that feminism is by no means a purely Western conception, oftentimes just the use of the word feminism evokes accusations of Western cooption in confrontation with Muslim fundamentalisms.

Feminism is not a monolithic entity. In fact, feminism in Muslim contexts, has taken many forms. I will break down these feminisms into two broad categories, but it should be noted that these categorisations are in no way static and are continuously subject to debate. There are feminists, both non-religious and religious women, who choose to work within a secular framework in the articulation of their rights. These women demand that the laws governing the family not be based on Shari’a. They are, of course, under the most pressure from fundamentalisms.

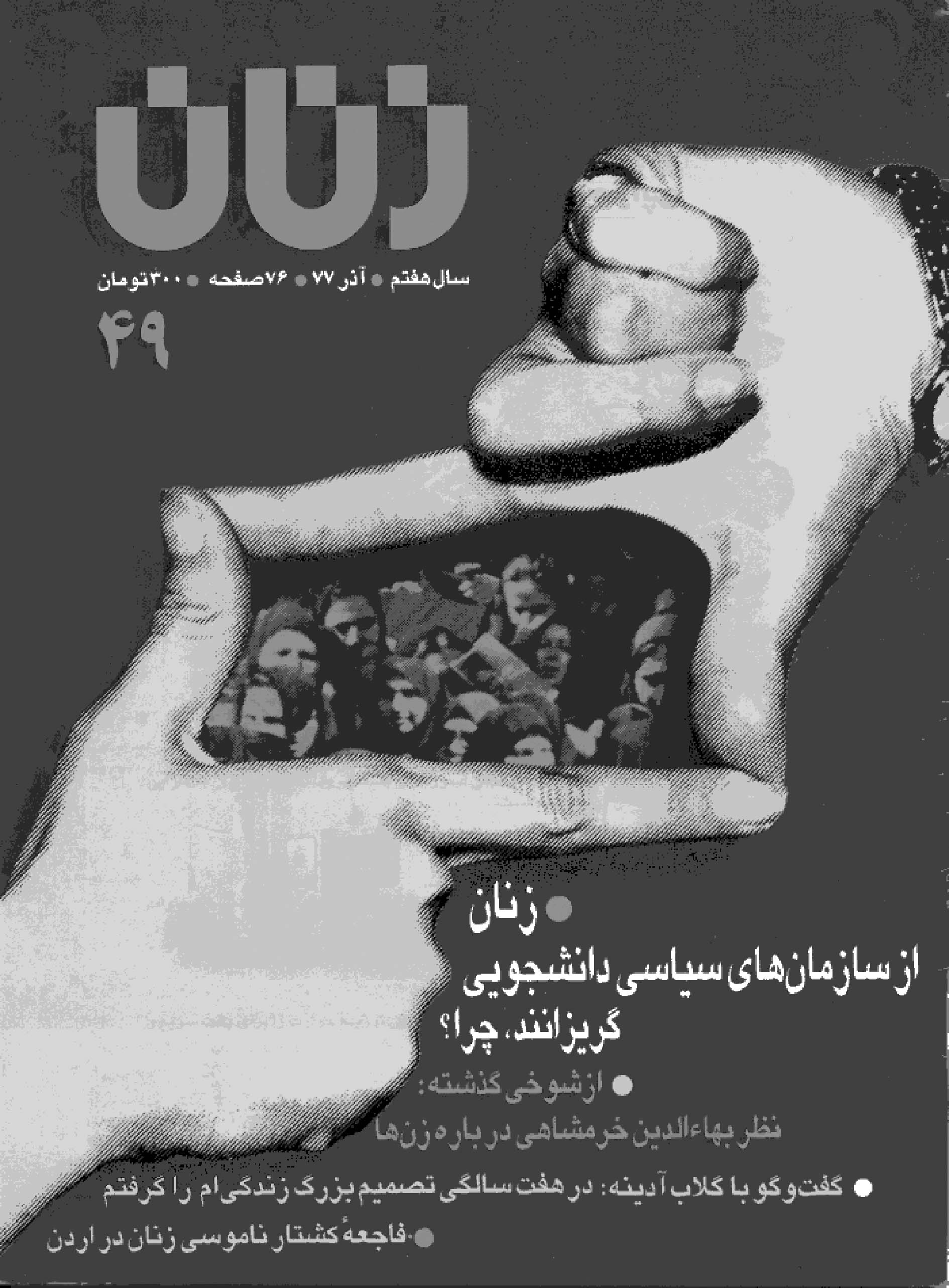

Recently the term Islamic feminism has also joined the debate on feminism in this region. Broadly speaking, Islamic feminism works to reconcile feminism with Islam in its cultural and political forms. This is why there is more than one conception of what Islamic feminism is. The first and most often articulated notion stresses a rereading of textual sources and a more egalitarian approach to Islam yet is also not hostile towards Western feminism. The women’s magazine Zanan, which began publication in Iran in 1992, can be seen as an example of this brand of feminism.

Zanan

After 16 years, Iran’s leading women’s magazine was ordered to be closed in early 2008. Meaning “women” in Persian, Zanan was accused of “offering a dark picture of the Islamic Republic through the pages of Zanan” and of “compromising the psyche and the mental health” of its readers by providing them with “morally questionable information.” Zanan featured articles on health, parenting, law, literature and other women’s issues.

Photo from the International Women’s Media Foundation.”

In photo is the city of Sanaa from Wikimedia Commons

More than 120 academics and humanMore than 120 academics and human rights activists like Noam Chomsky, Jurgen Habermas, Betty William and Shirin Ebadi protested the ban. Zanan was founded by one of Iran’s leading feminists, Shahla Sherkat.

Sources: Tehrani, Hamid (14 February 2008). “Iran: Protests over ban of women’s magazine.”; Learning Partnership (8 February 2008). “Zanan, Iran’s Leading Women’s Magazine, Shut Down by Government.” and New York Times (7 February 2008). “Shutting Down Zanan.”

As Ziba Mir-Hosseini described, Zanan advocated a brand of feminism that “takes its legitimacy from Islam, yet makes no apologies for drawing on Western feminist sources and collaborating with Iranian secular feminists to argue for women’s rights.” It reveals the lack of correlation between patriarchy and Islamic idealism but it does not conceal the gender inequalities in Islamic law. Moreover, it addresses such inequalities within the very context of Islam.

The second strand of Islamic feminism is an incredibly contentious one. It generally refers only to a small group of Iranian women who “seek the amelioration of the Islamied gender relations, mainly through lobbying for legal reforms within the framework of the Islamic Republic” (Mojab, 2001:130). These women, unlike women in the more “liberal” view of Islamic feminism, are quite hostile towards the use of the term feminism and Western feminism in general. One should also consider that these women are working to enhance their rights within the existing political structure of Iran. Its hostility towards the West might be a purely strategic choice. Hence there is an ongoing debate, both within and outside academia as to whether or not these women can actually be categorised as feminists.1

Even with women in parliament, women’s issues are still not a priority or even on the agenda. Rather, they represent the party in power and are only there to toe the line.

Although women in Muslim fundamentalist-influenced societies have been incredibly active and have participated in the gradual growth of civil societies, this activism has not been incorporated into official political power structures to any significant extent. In recent times there have been more women representatives in political institutions, but this has not translated into the representation of women’s interests. For example, the new Iraqi Constitution requires that 25 per cent of the 444 parliamentary seats must be occupied by women. This was a hard fought battle by Iraqi women activists because as Sundus Abass stated, “the quota in Iraq was actually put in the Constitution by the influence of the Iraqi women, because even the Americans were against adopting the quota in the Constitution.”

Even with women in parliament, women’s issues are still not a priority or even on the agenda. Similarly Iran installed some women members in parliament but they are not interested in women’s issues. Rather, they represent the party in power and are only there to toe the line.

Sources: Brown, John (19 September 2005). “Semi-Slave Conditions for Foreign Workers in Dubai.”; Sharp, Heather (4 August 2005). “Dubai women storm world of work.” and Shreck, Adam and Jamal Halaby (7 January 2010). “Dubai downturn sends ripples throughout Arab world. ”

Photo by Josa Piroska from Wikimedia Commons.

Conclusion

I have painted a general picture here of the situation of Muslim fundamentalisms and women in the Middle East and North Africa. Even though similarities can be drawn between different movements all over the region, in truth, the details of each specific context have led to the emergence of a distinct type of Muslim fundamentalism. Thus it is difficult to compare the situation in Morocco with that in Iran. Although religious fundamentalisms have been on the rise for a long time in this region, women are in no way passive victims. Many women actively resist. They fight for their rights, engage in social justice projects, and espouse various forms of feminism. While there is no doubt that veiled, homebound and uneducated women exist, such image in no way encapsulates nor acknowledges the lives and struggles of women in Muslim contexts.

References

Abass, Sundus (2006). “Campaigning for Women’s Rights in Iraq Today”. In WLUML Occassional Paper 15: Iraq Women’s Rights Under Attack – Occupation, Constitution, and Fundamentalisms, edited by S. Masters and C. Simpson. London: Women Living Under Muslim Laws.

Al-Ali, Nadje (2001). “Reflections on Globalization”. Unpublished paper presented at annual Gulf Studies conference at the Institute of Arab & Islamic Studies. University of Exeter.

Al-Ali, Nadje and Nicola Pratt (2009). What Kind of Liberation?: Women and the Occupation of Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gerner, Deborah J. (2007). “Mobilizing Women for Nationalist Agendas: Palestinian Women, Civil Society, and the State-Building Process”. In From Patriarchy to Empowerment: Women’s Participation, Movements, and Rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. Edited by V. Moghadam. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Hardacre, Helen (1993). “The Impact of Fundamentalisms on Women, the Family, and Interpersonal Relations”. In Fundamentalisms and Society: Reclaiming the Sciences, the Family, and Education. Edited by M. Marty and R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kandiyoti, Deniz (1993). “Identity and Its Discontents”. In Colonial Discourses and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. Edited by P. Williams and L. Chrisman. Essex: Pearson Education Ltd.

Keddie, Nikki (2007). Women in the Middle East: Past and Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keddie, Nikki (1998). “The New Religious Politics: Where, When, and Why do ‘Fundamentalisms’ Appear?.” In Comparative Studies in Society and History 40 (4): 696-723.

Legrain, Jean-François (1994). “Palestinian Islamisms: Patriotism as a Condition of Their Expansion”. In Accounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements. Edited by M. Marty and R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mira-Hosseini, Ziba (2005). “Muslim Women, Religious Extremism and the Project of the Islamic State in Iran”. In Muslim Women and the Challenge of Islamic Extremism, edited by N. Othman. Kuala Lumpur: Sisters in Islam.

Mojab, Shahrzad (2001). “Theorizing the Politics of ‘Islamic Feminism.” In Feminist Review, The Realm of the Possible: Middle Eastern Women in Political and Social Spaces, 69: 124-146.

Ottaway, Marina (2005). “The Limits of Women’s Rights”. In Uncharted Journey: Promoting Democracy in the Middle East. Edited by T. Carothers and M. Ottaway. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Rouhana, Hoda (2005). “Women Living Under Muslim Laws (WLUML) Network’s Understanding of Religious Fundamentalisms and Its Responses”. In Muslim Women and the Challenge of Islamic Extremism. Edited by N. Othman. Kuala Lumpur: Sisters in Islam.

Saghal, Gita and Nira Yuval-Davis (1992). “Introduction: Fundamentalism, Multiculturalism, and Women in Britain”. In Refusing Holy Orders: Women and Fundamentalism in Britain. Edited by N. Yuval-Davis and G. Saghal. London: Virago Press.

Shahak, Israel and Norton Mezvinsky (2004). Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel (New Edition). London: Pluto Press.

Tripp, Aili Mari (2006). “The Evolution of Transnational Feminisms: Consensus, Conflict, and New Dynamics”. In Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organizing, and Human Rights. Edited by M. Ferree and A. Tripp. New York: New York University Press.

Ziai, Fati (1997). “Personal Status Codes and Women’s Rights in the Maghreb”. In Muslim Women and the Politics of Participation: Implementing the Beijing Platform (1st ed.). Edited by M. Afkhami and E. Friedl. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Footnotes

1 This is an incredibly rich debate. It ranges from people like Hamed Shahidian who believe “Islamic feminism” to be an oxymoron, to those who believe Maryam Behrouzi – Iranian Majles deputy – to be a feminist. Maryam Behrouzi, who would not claim to be a feminist herself, pushes for more female political representation within the Iranian Majles (from her own conservative Islamist party). She and many other practising Muslims do not believe in equality between the genders, because the individual is not counted as the unit of society. The unit of Muslim society is the traditional family which is constructed by marriage between one man and at least one woman). Therefore, men’s and women’s roles, responsibilities, and hence rights are not equal but complimentary – for the sake of the family.

“I hope the victory will be spreading around the world and there will be no criminalization for Sexual orientation anymore,” said Poedjiati Tan, Female Representative of International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) Asia1

Photo from gaylife.org

On June 30, 2009 the Delhi High Court overturned a 148-year-old colonial law criminalising consensual homosexual acts, saying that it was a violation of fundamental human rights protected under India’s Constitution. This moment of joy for the LGBTIQ2 movement in India is shared by many in the world who supported them in their struggle.

In the last decades, the world has seen incredible changes in terms of LGBT rights in many countries across the globe and in all continents. In December 2008 the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity was signed by 66 countries. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Ms Navanethem Pillay described the criminalisation of same sex relations “in defiance of established human rights law”3.

At the same time, 80 countries around the world are still criminalising LGBT people for what they are. In five of them - Iran, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, parts of Nigeria and Somalia, LGBT risk death penalty by being themselves. In Burundi, Africa despite international protests a revision of the Penal Code was signed into law in April 2009 that for the first time in the countries’ herstory criminalises same-sex relations.

ILGA published its updated report on state sponsored homophobia in May 2009. It describes the legal situation in these 80 countries. It also shows the progress and victories with regards to LGBT rights such as which countries penalise discrimination on the bases of sexual orientation and recognise gender identities different from heterosexual patterns and which countries introduced same sex registered partnership or marriage.

The governments that criminalise LGBT people’s choices in life “cry out against a homosexual orientation as totally extraneous to their national culture, a poisoned gift imported from the decadent west, without noticing the paradox of enforcing – at the same time – homophobic laws, which represent the worst legacy of their colonial past or of a religion imported from elsewhere.”4

The decriminalisation of homosexuality and the protection of LGBT rights as well as the introduction of same sex registered partnership had in most countries a very positive effect such as less violence against LGBT people. People who were once confined to the closet are able to come out and live their love and gender identity openly, less stigmatisation and stereotyping. There is more tolerance towards variances to patriarchal heteronormativity. “Even though I am not a supporter of the patriarchal institution of marriage, it feels differently walking in public hand in hand with my partner knowing that my love has the blessing of the majority of the Swiss voting population who accepted the law on a registered partnership inferior to marriage.” commented a Swiss lesbian activist in 2005 after the plebiscite on same sex registered partnership. Unfortunately by no way all this positive developments mean an end to violence against LGBT people. Lesbians and female transgender persons are among the most vulnerable to so called hate crimes.

The countries’ macho politics lead to lack of action despite hate crimes against lesbians

South Africa was the first state worldwide that placed sexual orientation under the protection of constitutional law. Lately, an alarming number of black lesbians are being raped for their gender identity and s e x u a l orientation. Triangle, a South African gay rights organisation, says they are dealing with up to 10 new cases of “corrective rape” every week.

Despite more than 30 reported murders of lesbians in the last decade, the trial against the murder of the famous out lesbian player of the national female football squad Eudy Simelane produced the first conviction of all the “corrective rapes” perpetuated against black lesbians in South Africa. Eudy Simelane was gang-raped and brutally murdered in 2008. “When we try and report these crimes nothing happens, and then you see the boys who raped you walking free on the street.”5

Photo and sources: Black Looks (14 January 2009).”Accused for murdering lesbian soccer player go to trial" and (12 July 2007). “A Time of Hurt: lesbians raped, tortured and murdered”

Support groups claim an increasingly aggressive and macho political environment is contributing to the inaction of the police over attacks on lesbians and is part of a growing cultural lethargy towards the high levels of gender-based violence in South Africa. “When asking why lesbian women are being targeted you have to look at why all women are being raped and murdered in such high numbers in South Africa. So you have to look at the increasingly macho culture, which seeks to oppress women and sees them as merely sexual beings. So when there is a lesbian woman she is an absolute affront to this kind of masculinity.”6

The failure of police to follow up eyewitness statements and continue their investigation into another brutal double rape and murder of lesbian couple Sizakele Sigasa and Salome Massooa in July 2007 has led to the formation of the 07-07-07 campaign, a coalition of human rights and equality groups calling for justice for women targeted in these attacks.

Transgender persons are the most likely to be targeted by anti-gay commands in Brazil

Homophobia has been responsible for the killing of 2,403 gays, lesbians, and transgender persons in Brazil in the last 20 years, making Brazil have the highest number of homosexuals killed in the world. This prompted the government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silvato launch the Brazil without Homophobia program in 2003.

This was a historic moment for the advance of homosexuals’ human rights. Among many others it lead to Gay Prides in 49 cities, with Sao Paolo being the largest gay pride world wide with 1,8 million supporters. It also encouraged twenty-two candidates (13 gays, 6 transgenders, and 3 lesbians) to run in the 2004 municipal elections. A gay council member was elected in Vitória da Conquista and a transgender Vice Mayor was elected in the city of Colônia.7

On the sad side the campaign was not able to stop the violence against LGBT people in Brazil. The headquarter of the Brazilian gay organisation SOMOS in Porto Alegre has been the target of a neo-Nazi group on January, 21, 2009. Three swastika graffitis were painted on the walls of SOMOS headquarter building. The swastika cross is a symbol of hate against homosexuals, black and Jewish people.8

Source: Pink News – UK (2 December 2007). “Brazilian president calls national LGBT conference.

Photo by Fabio Rodrigues Pozzebom from Wikimedia Commons

In 2008, 190 homosexuals were killed in Brazil, one every two days, representing a 55 percent increase on the previous year. The Annual Report on Murders of Homosexuals, produced by the Grupo Gay da Bahia (GGB) documents crimes that are “specifically motivated by homophobia and prejudice”. It states among others that “A transvestite (female transgender person) is 259 times more likely to be murdered than a gay man.”9 While majority of the gay men were killed in their homes often stabbed using knives, 80 percent of the transgender persons were killed by fire arms in public places.

Marcelo Cerqueira from GGB, said the sharp rise in gay-bashing murders does not mean that more people were murdered but it rather indicated that more cases are being reported and is a result of “more effective instruments to monitor and register this kind of homicide.”

The LGBT movement in Brazil welcomes the Brazil Free of Homophobia programme by the National Commission on Human Rights. But it needs to take more compelling action. Special police units should be created to deal with hate crimes. Sex education should be included in school curricula “to teach young people to coexist with sexual diversity,” Cerqueira said. Another important step, would be to carry out official media campaigns against homophobia, along the lines of the government’s “Water for All”, “Electricity for All” or “Homes for All” campaigns.

Photo from Marion Cabrera.

The activist criticised the Brazilian media, especially comedy shows, saying they fuelled homophobia by ridiculing homosexuals. This kind of humour strengthens the idea that “it’s ok to laugh at or insult gays,” and from there to homophobic hate is just one small step, Cerqueira argued.

Two steps forwards in Asia one step backwards

While the court decisions in Nepal and India that decriminalise homosexuality are great victories for the LGBT rights movement, there are still 24 countries in Asia and nine countries in the Pacific that criminalise people who live their sexual orientation and gender identity. On the other side Australia, Fiji, Israel, Japan and New Zealand do prohibit discrimination in employment based on sexual orientation and same-sex registered partnership has been introduced in Israel and New Zealand. In Australia a respective law is being discussed in parliament. Japan, Turkey, Australia and New Zealand have a Law on Gender recognition after Gender Reassignment treatment.10

Many countries in Asia and the Pacific are indifferent about LGBT rights, neither do they have laws that criminalises homosexuality nor laws that protect people’s human right to freely live their gender identity and sexual orientation. But with the LGBT community becoming more visible and coming out in gay prides, demanding their basic human rights, we can observe the appearance of hate speech and insults by citizen groups against gay prides in countries where the societies are rather indifferent or tolerant to variances of patriarchal heteronormativity.

Many countries in Asia and the Pacific are indifferent about LGBT rights, neither do they have laws that criminalises homosexuality nor laws that protect people’s human right to freely live their gender identity and sexual orientation.

The gay pride marches last December 2008 and 2009 in Manila were attacked by members of Christian fundamentalist religious groups. They confronted the participants of the march with placards saying “Hell is waiting for you Gay, Lesbian Transsexual Repent”, “God will judge the sexually immoral” or “It is not ok to be gay it’s sin” and threatened and insulted them over megaphone. This had never happened before.

When Ang Ladlad, the first guy political party worldwide filed their canidacy for the elections in the Philippines the party was disqualified by the Commission on Election (Comelec) on the ground of immorality. Despite the Philippines being a secular country, Comelec included quotes of the Bible and the Koran in its resolution. After widespread protests the Supreme Court temporarily restrained the Comelec from disqualifying “Ang Ladlad” from the elections in May 2010. As of January 23 the final decision was still pending.

Practising Pluralist Politics: Implications on Feminist and LGBT Organising

by Tesa Casal de Vela and Mira Alexis P. Ofreneo

Fifteen years ago, women’s groups fighting for women’s sexual health and sexual rights successfully negotiated for the inclusion of women’s right to control their sexuality in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPFA). Though the terms “sexual orientation” and “sexual rights” were eventually excluded from this historic UN document, the inclusion of matters related to “sexuality” paved the way for discussing sexual health and sexual rights in feminist agendas. Fifteen years later, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activists ask if the recognition of sexual orientation and gender identity as legitimate concerns of feminists has moved beyond symbolic recognition to concrete action.

Fifteen years ago, women’s groups fighting for women’s sexual health and sexual rights successfully negotiated for the inclusion of women’s right to control their sexuality in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPFA). Though the terms “sexual orientation” and “sexual rights” were eventually excluded from this historic UN document, the inclusion of matters related to “sexuality” paved the way for discussing sexual health and sexual rights in feminist agendas. Fifteen years later, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activists ask if the recognition of sexual orientation and gender identity as legitimate concerns of feminists has moved beyond symbolic recognition to concrete action.

In the recently concluded Asia Pacific Forum for Beijing +15 last October 2009, a group of feminist and LGBT activists created a space for a discussion on “Practising Pluralist Politics: Implications for Feminist and LGBT Organising”. The workshop was sponsored by the Kartini Asia Network, the International Lesbian & Gay Association (ILGA), Isis International and Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN).

As we organised the workshop, our premise was that heteronormativity still exists in feminist movements, a hegemony that privileges heterosexual women’s concerns. Such heteronormativity marginalises the issues of lesbians, bisexual women, and transgendered people and reinforces their social, cultural, political, and economic invisibility. It seems that there is a need to learn about the sexual hierarchies that not only exist in dominant mainstream cultures but also the sexual hierarchies that exist in ‘alternative’ subcultures such as feminist and LGBT movements.

The workshop attracted a handful of women from diverse geographic locations. Wanting to create an atmosphere of openness, a circle was formed and all were asked to freely share their experiences related to issues of sexuality, within and outside political movements. The sharing started with the three assigned “speakers” who jumpstarted the conversation. Because a number of attendees of the workshop expressed concern about the confidentiality of their identities, all names are kept in confidence – in solidarity with those who cannot come out for one reason or another.

Identity as facilitating and hindering my politics

The first speaker, identifying herself as a lesbian traced her experience with sexuality as far back as when she was six No.3, 2009 WOMEN IN ACTION years old. It was then that she realised that she was attracted to girls and not boys. For years, she had to secretly deal with these same-sex attractions. She recalled how the process of naming her experience was important to her selfhood. Coming out and embracing her lesbian identity during her teenage years was part and parcel of her struggle for social acceptance and self-affirmation. However, now that she is very much identified as a lesbian activist, she has found this same identity as limiting her political involvement. She finds that her lesbian identity becomes her prime and often sole political identity.

Affinity with the marginalised identity of others as my politics

The second speaker talked about her strong empathy and commitment to addressing the issues and concerns of those from marginalised identities and locations, despite or because of her own identity as a heterosexual, white, middle class woman. She talked about her work with men and women of diverse sexualities, as well as her development work with black Africans as a cultural artist-activist. But this empathy and commitment had not necessarily been enough for some of the circles she moved in. She experienced her own share of being perceived as belonging to a privileged socio-economic position and therefore often found herself having to explain why she did the work she did, why she believed in the politics that she did.

Identity as not having the space to be expressed or discovered

The third speaker did not label her identity and instead went into how, in her culture, there is no opportunity to express, explore, or even discover one’s sexual identity. She described that the degree of socio-political repression in her culture was such that sexuality was not a matter an individual could control or even think about. Rather heterosexuality was dutifully performed. Women like herself get married and have children, growing old without exploring who they are as sexual beings or what they really want or desire. Exploring homosexuality could have consequences of criminalisation, even death. It was only through her activist work outside the country was she able to learn about sexual rights and sexual identity.

A sharing of and from multiple identities

An open sharing of experiences from the small group of women ensued. Many women talked about coming out as a lifelong struggle in their personal and political lives. Within this safe space, a young woman activist came out though she has not carried a lesbian identity in her own country. One lesbian activist felt marginalised within the larger feminist space of the conference. But the women acknowledged that they could not obligate a movement to be open and inclusive, they could only advocate it. Still, the feminist movement was seen as having not a right but a duty to take on the struggles of women with marginalised sexual identities. An older heterosexual feminist posed the idea that women had multiple identities, with sexual identity being only one of these. And in certain situations within political organising, women may project one identity over the other, making sexual identity not necessarily always the prime in a given political space. She likened this process to wearing different masks. But a young lesbian feminist begged to differ. While she agreed that women had multiple identities, she did not think these identities could be taken off that easily when engaging in political work. She believed her multiple identities were pieces of one mask, a mask that she could not take off because it was who she was.

Towards pluralist politics

Surfacing differences within LGBT activists and feminists should not be a threat to collective political action. Rather, our alliance can be strengthened if we organise not because of the same identity or an essential sameness but rather because of a shared commitment to freedom from all forms of oppression. Hence, pluralist politics is a politics informed by multiple, conflicting identities and locations. It means living in tension but being comforted by a shared commitment to fight for the freedom from oppression, even if these oppressions are diverse. It means embracing conflict and contradiction but moving towards continually articulating and rearticulating the social movements’ agenda. Pluralist politics then allows for the recognition of specificity and difference without letting go of the dream for equal rights for lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgenders, within and beyond the feminist movement; and the vision for freedom for people of diverse genders and sexualities.

- Originally published in Dawn Informs (January 2010)

After a very successful first gay pride in Chiang Mai in conjunction with the third ILGA Asia conference in January 2008, LGBT rights activists organised the second gay pride in Chiang Mai in 2009. Before the event suddenly a lot of complaints and false information was circulated and the organisers were struggling hard to make the gay pride happen. The participants of the gay pride were stopped and verbally attacked by fanatics wearing read t-shirts and carrying placards saying “Stop Gay Parade now” (Stop Now! Parade’s Gay) “We do not want Gay Parade” (No Want Parade’s Gay).

“Homophobia is often the result of a certain time and context in history, a time and a context always marked by a strong inequality between men and women. Indeed, at the heart of homophobia, lesbophobia and transphobia lies the belief that men and women should not be equal, should play roles incompatible with each other and should be confined in a hierarchy where the former dominate the latter.

No wonder that in such a context a man perceived as treating another man as a woman or a woman perceived as behaving like a man are considered a threat to a supposedly natural order, an order so natural that it takes all the force of organised agencies, be it of traditional, religious or governmental kind to maintain itself. But if homophobia is a cultural phenomenon, something which is learned, it is every decent person’s duty to fight and isolate those who are teaching it.”11

Footnotes

1 ILGA International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Association

2 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer (in this article referred to as LGBT people)

3 State-Sponsored Homophobia by Daniel Ottosson and ILGA, May 2009, www.ilga.org

4 Gloria Careaga & Renato Sabbadini, Co-secretaries General of ILGA in State-Sponsored Homophobia, May 2009

5 Zakhe Sowello, Raped and killed for being a lesbian: South Africa ignores ‘corrective’ attacks, www.guardian.co.uk, March 12 2009

6 Carrie Shelver, or the South African NGO Powa, same

7 Toni Reis, General Secretary of the Brazilian Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender Association

8 www.ilga.org press release

9 Fabiana Frayssinet, “RIGHTS-BRAZIL: Gay-Bashing Murders Up 55 Percent”, April 22 2009

10 Report on State Sponsored Homophobia by Daniel Ottossonand ILGA report, www.ilga.org, May 2009

11 Gloria Careaga & Renato Sabbadini Co-secretaries General of ILGA in “State Sponsored Homophobia” May 2009

Where Reproductive Rights Are A Joke: Poland, Politics and the Catholic Church

May and June is the time of first communion celebrations in Poland. Since Polish people are predominantly Roman Catholic, little girls and boys who are dressed up like smaller versions of brides and grooms are to be seen everywhere – on the streets, shopping malls, returning from different church occasions. A couple of days ago, I came upon an article1 on how this tradition is turning into a more and more commercial event.

What frightened me more than the stories of children driven to church in pink limos was the mention of pledges taken by these 8-year-olds in some parishes. Besides swearing not to consume any alcohol and drugs, girls and boys are made to take an oath to “remain chaste” until the age of 18. I could not help but wonder – how do these kids know what their pledge really means?

Most Polish parents lack the skills and courage to talk to their children about sex. But I also assume that nobody explains the details of “chastity” to those young ones.

The Roman Catholic church in my country is not just an institution. It is a force that has been trying to control people’s thoughts and lives by repressing their sexual freedom. What makes things worse is that priests and bishops have the obedient, God-fearing politicians of the right-wing parties ready to turn the most conservative Catholic teachings into binding laws. This combination of circumstances has never brought any good to women and discriminated groups.

Why exactly is the church in Poland so powerful that almost every draft law is sent to the episcopate with request for opinion? Not so long ago, in the 1920s and 1930s, my country was a place where different cultures, religions—Catholicism, Russian Orthodox Church and Judaism—and points of view coexisted. But World War II changed everything.

Decades of communism have hindered the development of civil society and have made people passive. There was no second wave feminism, no fight for gay rights.

Today, the Polish population is extremely homogenous – everyone is white and Catholic - you hardly ever see a person of different race, ethnicity or faith. Decades of communism have hindered the development of civil society and have made people passive. There was no second wave feminism, no fight for gay rights. The only social movement that thrived during those times was the anti-communist opposition which was supported by the church. Heroes of the “Solidarity” movement are almost exclusively males – priests, bishops and devoted Catholics, like the first democratically elected president Lech Walesa who never appears in public without a brooch with the picture of Virgin Mary pinned to his jacket.

Perhaps the church and state relations would be different if it was not for pope John Paul II who had encouraged the repressed Poles to rebel against the atheist regime and contributed to the end of communism in Poland.

Photo by Slawek from Wikimedia Commons

The Catholic Church represented everything that the communist party disregarded. Practicing one’s faith in that period was not only about religion. It was a subversive act against the authorities who claimed there was no God. Sharing the conservative position of the church on such issues as division of gender roles or abortion was desired because it was a sign of disobedience.

When the communists imposed their vision of social equality, promoting it with posters of smiling women on tractors and opening free childcare facilities so that mothers could join the socialist work force, the wives of opposition activists stayed home, raising their children and supporting them in silent prayers. When the communists allowed women to terminate pregnancy on demand, protesting against it and quoting the pope’s teachings on the sanctity of life from the moment of conception was in order.

When democratic transformations in Poland began, the bishops held on to their political role. The influence of Catholic ethics is clearly seen in the Polish Constitution of 1997 where marriage is defined as a “union of a man and a woman.” 2

In 1993, on the initiative of Catholic members of Parliament, the new antiabortion law was passed, making the procedure illegal except for cases of maternal health threat, serious fetal abnormalities or rape. The law was liberalised for a brief period only to return to its restrictive form in 1997.

When the left-wing party was in power, a new law was drafted in cooperation with prochoice NGOs and experts but the bill was never voted upon. Many say that this was a result of secret dealings between politicians and church hierarchy who allegedly promised to convince Polish people to vote “yes” in the referendum on Poland’s EU accession in exchange for leaving the abortion issue alone. Nobody knows for sure how it really was but the so-called abortion compromise is still in force.

The Polish Pope

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps the most popular pope of the 20th century, John Paul II was the first non-Italian cardinal to assume the highest position in the Catholic church. He likewise came from a country that was under the influence of the Soviet Union. Although John Paul II instituted significant changes in the Catholic church, including the latter’s acknowledgement of its past crimes such as the death of Galileo, its role in the Inquisition and slavery and the murder of Muslims during the Crusades, he was quite conservative on women, abortion, contraception and sexuality.

He never approved of the ordination of women in priesthood, which was the only way for women to asumme higher positions in the Vatican. Although the church’s teachings on the viability of life have changed over time, John Paul II had an uncompromising stance on abortion and contraception especially in the South where Catholicism has a huge following. Some also consider his apology for people who have been sexually abused by priests lame. While he did not consider homosexuality as a sin, he nevertheless found immoral partnership between persons of the same sex.

Some people may say that John Paul II was a feminist pope with his position against violence against women and his appointment of a few women in critical positions such as the Vatican Theological Commission. However his term consistently followed the church’s harsh bias against women especially on issues relating to women’s bodies.

As Angela Bonavoglia, author of Good Catholic Girls: How Women Are Leading the Fight to Change the Church commented, “[The Catholic church] is against war except under very specific circumstances. But it has never said anybody who supports those things cannot come to communion, must be turned away at the altar, but it has taken that position with abortion. And on a purely political level, I think we have to ask why. You can say that to women, and you’re not going to get as much opposition as if the Church hierarchy had said to anybody who supports preemptive war or capital punishment you cannot come and receive communion.”

Source: Goodman, Amy (5 April 2005). “The Legacy of Pope John Paul II.”

The abortion status quo has had a huge impact on women’s lives and contributed to social inequality. Officially, there are about 200 legal abortions performed in Poland every year. Unofficial estimates are as high as 200,000. Only a very naïve person would believe that in a country of almost 40 million people, with poor sex education, difficult access to contraception and falling birth rates, only a handful of women would seek to end their pregnancies.

But the reality looks different – women with means go abroad to have the procedure or pay big sums for underground but usually safe abortions performed by doctor in Poland. Those who are in a difficult financial situation, for example frightened teenagers who would not want their parents to learn about their pregnancy, resort to ordering abortion pills online. Yet using these pills incorrectly can lead to serious complications.

The anti-abortion pressure has been so high in Poland that even the women who had a legal right to terminate their pregnancy have difficulty exercising their rights. The best known example is the story of Alicja Tysiac, a woman who had been denied the right to abortion and almost lost her eyesight due to her third pregnancy. Recently Tysiac has brought a civil lawsuit against the editor-inchief of a Catholic magazine Gosc Niedzielny which published a series of articles condemning the woman’s attempts to undergo an abortion as “wanting to murder her child”.

Another shocking case is that of a 14-year-old girl’s pregnancy that is thought to have been the result of rape. The girl demanded legal abortion but one hospital refused to perform the procedure on the basis of the conscience clause. Worse, it breached the patient’s right to confidentiality as the hospital notified a priest and anti-choice activists who visited the girl, obtained her telephone number and tried to convince her not to terminate. The girl traveled with her mother to Warsaw where she was followed and harassed by opponents of abortion. When they complained to the police and were taken to the precinct for interrogation, officers allowed the priest to participate in it, despite the fact that he was one of the possible suspects in the case.

Officially, there are about 200 legal abortions performed in Poland every year. Unofficial estimates are as high at 200,000.

When the girl finally had an abortion, one of the Polish bishops, Stanis Baw Stefanek commented3 that “the ideology of death was victorious” in this case. This cruel statement shows clearly the disregard of church representatives for women’s – and in this case, the girl’s well-being.

There are probably many more cases like Agata’s in Poland. Every year, about 300 girls aged under 15 years give birth. In 2008 alone, almost 20,000 Polish teenagers aged between 15 and 19 became mothers.4 This is not going to change without proper sexuality education that is based on scientific knowledge instead of ideology. Unfortunately, the present situation is far from perfect.

The existing law provides for about 14 hours a year for the subject “Preparation for Family Life” but it is not obligatory. Some schools do not bother to provide any education in this field.

For over seven years, I have been a volunteer in the Group of Sex Educators, “Ponton.” Recently we have conducted a study among young people on what their sex education inschool was like. We were shocked to see that what should have been a neutral education had been mixed up with religion. According to the law, Polish students are obliged to attend two lessons of religious education or ethics a week. In practice, the choice of the subject is very limited as most schools do not provide a teacher of ethics. But the schools assign a religious education teacher, most often a priest or nun.

Every year, about 300 girls aged under 15 years give birth. In 2008 alone, almost 20,000 Polish teenagers aged between 15 and 19 became mothers.

This version of religious education does not mean learning about different faiths and traditions for these classes focus strictly on the teachings of the Roman Catholic church and leave little room for discussion. During those lessons teachers often take up the subject of Catholic sexual morality, condemning abortion as murder or homosexuality as a deviation. What is even more worrying and curious is that in some schools, it is a priest or a nun who is assigned the classes of “Preparation for Family Life.”

This is a clear contradiction of modern sex education standards, which demand that the subject be science-based. Instead of reliable knowledge, young girls learn that they should remain virgins until marriage, otherwise they would be “like an apple that has already been bitten and nobody would want them.”

Myths and stereotypes like this cause enormous confusion with which we have to deal every day in our work as sex educators, answering letters from desperate teenagers who are worried that they will become infertile if they masturbate or believe that condoms have holes big enough to let HIV virus through. In our work, we have also received complaints from people who had been shown in class the manipulated and drastic anti-abortion films like the “Silent Scream” when they were very young.

The Polish church interprets the pro-life teachings in an extremely conservative and narrow way. Sometimes it can lead to paradoxes, like the one happening now around the debate on the new law on in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments for infertile couples. Despite the ageing population and low birth rates, the bishops have decided to go into war against IVF procedures, condemning infertile couples who have undergone this type of treatment in the hope of having a child.

When the government announced it was considering refunding IVF treatments for infertile married couples, the bishops’ conference decided to interfere. Before Christmas of 2007, they issued a letter appealing to parliamentarians not to support the solution. In a harsh language, they said that IVF was inadmissible and wicked. It described the method as a “sophisticated abortion,” 5 due to the fact that the procedure usually leads to the destruction of several embryos. Big discussions broke out and many Catholic couples felt hurt by this statement, not to mention gays and lesbians whose reproductive choices of couples have not altogether been taken into account.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people still have a hard life in Poland, especially in smaller towns and villages. Here, the attitude of the Catholic church also plays an enormous role. In 2005, when the current Polish president Lech Kaczynski was still Mayor of Warsaw, he denied LGBT activists the right to hold an Equality Parade, saying that this would upset the religious feelings of many. The sad truth is that his position was a reflection of general opinion in the society. According to a recent poll6 66 per cent of Poles are against gay pride marches, 90 per cent reject the possibility of gay men and lesbians to have the right to adopt children and a mere eight per cent regard homosexual orientation as something normal.

No surprises there if you consider that schools teach children that being gay or lesbian is a deviation and can be cured. Authors of many course books used in teaching the “Preparation for Family Life” subject were clearly guided by Catholicism on the issue, saying for example that a gay man or lesbian woman ought to remain sexually abstinent.

Respected public figures further reinforce prejudices by using hate speech in reference to the LGBT community. When a moral authority like bishop Tadeusz Pieronek tells the public that gays are not fit to work as school teachers or when the Solidarity movement hero, former Polish president Lech Walesa adds that homosexuality should be treated, people start believing something is wrong in the lives of LGBT.

It is not easy to be different in this country. When I was reading the article about first communions I was equally surprised with the idea of virginity pledges for 8-year-olds as with the hypocrisy and conformity of their parents. A typical Polish Catholic does not study Bible before going to sleep. She/he attends mass irregularly except during holidays, weddings and funerals. She/he does not practice what the Vatican preaches in terms of using condoms, the sanctity of marriage or abortion. The only problem is that few people are willing and ready to talk openly about the fact that they disagree with some of the strict teachings in the morality sphere.

Personally the road was quite different. Being raised Catholic I grew up to become a pro-choice feminist. I figured the two could never come together, not here, so I stopped practising my faith. It was only when I met people from the United States (US)-based organisation, Catholics for Choice (CFC) and became one of their European advisors did I realise that it is possible to reconcile one’s non-traditional views with one’s religion.

Still, when I openly talk about my opinions in Poland, I hear comments like “you can’t be Catholic and support liberal abortion laws, it’s not possible”. Nonetheless, these encourage me even more to continue the faith in my advocacy, my vocation, my choice.

Endnotes:

1 Pawe B. Moskalewicz, Judyta Sierakowska (10 June 2009). “Rodzice u komunii Przekrój”

2 The Constitution of the Republic of Poland (1997). Chapter I, Article 18

3 Tomasz Nie[pia B (19 June 2008). “14-latka usun ’Ba ci|’”; „Rzeczpospolita”

4 Central Statistical Office in Warsaw (2008). “Demographic Yearbook of Poland 2008"

5 Nasz Dziennik (19 January 2007).

6 Public Opinion Research Center (CBOS) (June 2008). Opinion poll “Gay and Lesbian Rights”

Cracks On a Cauldron of Cantons: The Chinese Question in Southeast Asia

The possibility of forming national communities had been initially welcomed after centuries of living under colonial rule. But contrary to its promise of inverting the restrictive and oppressive mechanisms that the colonial powers had instituted, the new national communities instead have perpetrated the same principles of inclusion and exclusion, resulting in the communities’ both cohesion and fragility.

Among the groups which have often been marginalised in the design and implementation of national communities (held together by equally suspect concepts of national identiy) are the ethnic minorities who have thrived by negotiating the spaces between the colonising powers and the colonised indigenous majority. Their survival has been almost unproblematic for the ambiguity of their presence enabled them to reap various resources without being stymied by the colonial authorities in the same way that the latter Among subjected the indigenous majority to a myriad of conditions.

Read more: Cracks On a Cauldron of Cantons: The Chinese Question in Southeast Asia

Mauritius: Communities of Paradise

Mauritius: Communities of Paradise

Walk down the main streets of Mauritius and one would perceive a striking mixture of peoples. This is a society that has come out of the grindstone of history and emerged with a plethora of ethnicities, cultures, traditions, and religions. This mélange of identities is a source of pride on one hand and a tripping point of tensions on another.

In photo is the Rodriguez beach by B. Navez from Wikimedia Commons.

And yet Mauritians would be the first to say that they live in a tolerant society, that people live harmoniously and without fear of hatred because of their colour or religion. Nevertheless, such diversity does have its pockets of discontent that is increasingly being expressed as intolerance, hate and even violence. When the mixture is stirred too much, not all things blend, they boil over.

Where does this much vaunted notion of tolerance and harmony in Mauritian society come from?

Like the spiciness that is the keenest features of its cuisine, Mauritius was cooked from various elements, the major ingredients being colonisation, slavery and immigration.

The islands that comprised Mauritius were dormant volcanic chains occupied only by tropical vegetation and a diversity of fauna including docile land tortoises and flightless birds. Its isolation from major landmasses and its vulnerability to tropical weather made it not viable enough for colonisation, such that half-hearted colonisers saw little reason to stay after beating down the dodos, clearing up the ebony trees and surviving a few cyclones.

Slavery was so pervasive that it constituted the backbone of Mauritian society under the French. More slaves were brought into the country continuously even until the British took the country by war in 1810.

Eventually the Dutch were able to set up a colony in the 17th century, bringing in sugarcane and slaves. They seem to have considered this effort a failure, and so abandoned the island in 1710. A few years later, the French took over the island and systematised the slave labour system that powered the sugarcane economy and linked it up to the trading system that connected India, the Arab peninsula and Africa. France also held naval power in the area through its colonies in Reunion and Madagascar.

Slavery was pervasive that it constituted the backbone of Mauritian society under the French. The slaves were taken either from eastern parts of the African continent or Madagascar. This outpost of the French empire was resistant to reform. Whereas in Paris there was already an abolitionist struggle, culminating in a law that abolished slavery in all its forms in 1794, in the colonies, the landowners did not even bother to follow this law. More slaves were brought into the country continuously even until the British took the country by war in 1810. The slaves developed a form of simplified French, stripped of much structure and grammar and borrowing from the languages of the enslaved peoples: Kreol became the common language for the islands in the region.

By the early 1800s, the British had set up a mode of compensation for landowners to give up their slaves. To maintain its economic production, “indentured” labourers were imported initially from China, Malaysia, Africa and Madagascar and then eventually, most labourers were brought in from various parts of the Indian subcontinent. These various peoples brought with them their own practices, belief systems, castes, biases and interests.

Mauritians in communal identities, unities and divisions

By the time of independence from the British in 1967, Mauritian society was already stratified and pluralistic. There are Creoles (who are descendants of African slaves), Franco-Mauritians (the descendants of white Europeans), people of mixed European and African descent (who are also called Creoles but some who consider themselves white to a greater degree, and who would call themselves Coloured), the people of Indian origin (Indo-Mauritian) and the people of Chinese origin (Sino-Mauritian).

Resentments have festered among the working class Creoles who see the wealth of the Franco-Mauritians as a product of slave labour and should be redistributed.

The Indo-Mauritians would distinguish themselves by religion, thus there are the Tamils, the Hindus and the Muslims. Some notion of caste is also recognised among the Hindus. In fact, caste becomes visible during election season when political observers note that the leaders of parties seem to come mostly from the dominant caste. Bhojpuri, a mixture of Hindi, French, Pharsi, Chinese among others, was historically the common language among the Indo-Mauritians, but a desire for ethnic pride is rekindling an interest in speaking Hindi among Hindus in Mauritius.

Oonk (2007) observed that the Indo- Mauritians did not begin to think of themselves as separate Hindi and Muslim communities until 1947, when Muslimdominated Pakistan was formed out of India. This historical event influenced the thinking of Indian diaspora communities in Mauritius to assert differing identities. Meanwhile, some Hindus are seeking a kind of idealised identity and fostering a kind of extreme Hindu nationalism similar to that which is on the rise in India.

Photo by Lonely Planet- Germany from Wikimedia Commons

Membership by descent and by religious affiliation in a community is a source of identity for most Mauritians; thus they refer to their own groupings as the Tamil, Hindu and Chinese communities. In terms of identity, the Creoles exist in their own hierarchy of colouredness and mixed ethnicity; they do not necessarily think in terms of a Creole community, and politically they are referred to as the “general population.”

Economic stratification also exists which is linked to ethnicity: Franco-Mauritians are still major landowners and run big industries. Increasingly their ranks are joined by some Indo-Mauritians and Chinese. Resentments have festered among the working class Creoles who still see the wealth of the Franco-Mauritians as a product of slave labour and should be redistributed. Working class Creole sentiment is expressed best in the sega, a music that has hybrid characteristics similar to other African diaspora cultural expressions. The government is making an effort to promote a sense of identity among Creoles, through concerts and cultural festivals that look back towards African roots. Meanwhile, Creole leadership has come mostly from the Roman Catholic church. Creoles, Franco-Mauritians and some Sino- Mauritians are mostly Christian, predominantly Roman Catholic.

Communalism becomes a divide-andconquer tactic when the political parties recruit and field their candidates while reserving a token number of electoral seats for those who were marginal through what is called a “best-loser” system.

“Communalism” is at once a negative word among Mauritians and also an acknowledgement that diversity does not always bring harmony. To be communal is about holding true to the values and traditions of your ethnic or religious grouping. At the same time, being communal also refers to a sense of intolerance, so that one will uphold the rights, values and traditions of one’s own community at the expense of other’s communities.

In the political arena, communalism becomes a divide-and-conquer tactic when the political parties recruit and field their candidates, seemingly employing a calculated sorting to ensure that there would be enough from certain communities to gain the votes while reserving a token number of electoral seats for those who were marginal through what is called a “best-loser” system.

Harmony and sharing, or name calling and hate-mongering?

Mauritians tend to be proud of their cultural diversity. They cite many instances when the various communities exhibit cooperation and harmony.

On religious holidays, people from a community share cakes, join festivities, greet each other: “Bonne fete!” In these instances, a sense of unity falls on the whole island, aided by the rhetoric of the government leaders speaking about multiculturalism and harmony between communities on national television. In the towns, mosques broadcast their daily calls to payer, a few hundred meters away from a colourful Tamil temple, and down the road, the Catholic church rings its bells.

The schools, which are subsidised and regulated by the state, are run by either secular or religious organisations, and yet they enrol children from different communities; a law prevents them from discriminating in favour of children from a specific community. And yet—there are many words that occur in the Kreol language, many of them used in a derogatory manner:

Nasyon = referring to a Creole

Lascar = referring to a Muslim

Malbar = referring to a Hindu

These words do not arise in polite conversation, except perhaps as banter between friends. However, a scan of online discussion groups show how Mauritians (under the relative anonymity of the Internet) feel free to call each other derogatory names when talking on Mauritian issues. On one discussion group, some Mauritians (many of whom were apparently not living in Mauritius anymore) were talking about how usually a “malbar” girl would represent the country in the Miss World contest. Some replies to this post pointed to how the current representative was actually creole-milat (mulatto), and then the conversation deteriorates from that point.

At the edge of tolerance – racial and ethnic discontent

The connectivity between intercultural conflict and economic disparity is alluded to by some analysts of Mauritian society: “If poverty hits particular groups within a small multiethnic society, the country runs the risk of having to face diverse forms of conflicts and interculturality becomes threatened. Interculturality can only be real and genuine if social justice prevails, if every citizen is given an equal chance and he or she perceives that this is the case.” (Bunwaree, 2002)

Photo by Malyn Ando

When Mauritians think of race conflict, they can look back to a fairly recent event: the riots that followed the death of the sega musician Joseph Reginald Topize, known more popularly as Kaya. A Rastafarian by belief and Creole by ethnicity, Kaya was arrested for participating in a protest calling for the legalisation of marijuana in 1999. He died in prison due to what was widely believed as police brutality. His death galvanised anti-Hindu sentiment and class discontent among working class Creoles, leading to riots in the major towns in February of 1999.

Ethno-religious conflict has not been seen in recent years. However, the media has reported the increasingly questionable and sometimes aggressive actions of a group calling themselves the Voice of Hindu (VOH). Their page on the social networking site Facebook describes their goals as “All Hindu must be in the same way, to fight our enemy now we have the power in Mauritius we can do as we want we must take control of the world we must be more powerful to do this. for that we must join all our Hindu brother to make one force.... (sic).”

Mauritian novelist Lindsey Collen recounted how her own novel The Rape of Sita was subjected to censorship for drawing metaphors from Hindu mythology. She also mentioned how some VOH members tried to physically remove a painting on exhibition which had a non-traditional depiction of a Hindu goddess. VOH have been credited with intervening in “mixed marriages” (such as between Hindus and Muslims), and in vocal attacks against media that has been critical of Hindu leadership.

Gender at the intersection of Mauritian ethnicities, religions and classes

Where diversity exists, additional tensions can also occur when new factors enter into a system. For feminist activist and GenderLinks Mauritius director Loga Virahsawmy, the economic successes of Mauritius brings problems. She acknowledges that gender inequality differs along cultural lines:

“There are some women who can go to cinemas, who drive cars but there are some women, who depending on their culture, shouldn’t go out at night, should obey their husbands.

With the opening of the EPZ (export processing zones), women in Mauritius have had the chance to get economic independence, to go and work in industries. But then, men couldn’t accept that their wives had economic independence. They’ve become violent. So violence has become on the rise.”

Conclusion

Mauritius may still outpace any threats of disruption. Many aspects of Mauritian society point towards more unity rather than conflict. Erikse (1998) and Sisisky (2006) cite a few: the smallness of Mauritian society, the pervasive use of Kreol as a shared language, the shared history as immigrants, the developing meritocracy in the private sector, and greater interaction and intermingling particularly in the younger generation.

However, there are aspects of society that need to be addressed: the feeling of disenfranchisement within the poorer Creoles, the perpetuation of communalist thinking in the political system and the economic and political dominance of certain groups. It is these areas that the Mauritian government has been seeking to address in some programs.

Whether matters come to a boil in Mauritian society depends on how such areas of tension and potential conflict are managed by its leaders and reacted to by its own citizens.

Sources and further reading

Oonk, G (Ed.) (2007). Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. University Press: Amsterdam.

Boswell, R. (2006). Le Malaise Créole: Ethnic Identity in Mauritius.

Hand, F. (nd). “Ene sel le pep ene nasyon: Seggae as a Creole Challenge to Mauritianness.”

Erikse, T.H. (1998).Common Denominators: Ethnicity, Nation-building and Compromise in Mauritius. Oxford and New York: Berg Publishers.

Collen, L. (2006). “Art for Life and Death.”

Bunwaree, S.S. (2002). “Economics, conflicts and interculturality in a small island state: the case of Mauritius.” Polis 9 (Numéro Spécial), 1–19.

Sisisky, C. (2006). “Mauritian Hinduisms and Post-Colonial Religious Pluralism in Mauritius.”

Page 1 of 2

The

The

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.

Isis Resource Center holds one of the largest feminist collections of materials in the Global South. With 40 years of publication experience, Isis holds a vast collection.